If you don’t know a pliosaur from a plesiosaur, how do you devise an exhibition about them and other prehistoric marine reptiles? How do you decide what approach to take and what items to include? And how do you find fossils or make replicas? Em Blamey takes us through the creation of Sea Monsters: Prehistoric Ocean Predators.

As a creative producer at the museum, I’m tasked with developing exhibitions that are not based on our collections. My previous major projects have been family-friendly experiences based on Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas and Horrible Histories® Pirates.

To help us determine future exhibition topics, we conduct audience research. When this indicated that visitors would be keen to see an exhibition on prehistoric marine reptiles (the ‘dinosaurs’ you can do in a maritime museum), my next project was decided. At that point however, I knew very little about them. Like most people, I went through the dinosaur stage while growing up, and I still knew my Stegosaurus from my Spinosaurus – but not their salty cousins. Luckily, there’s a MOOC – Massive Online Open Course – for that! I completed a fascinating and free course on the palaeontology of ancient marine reptiles by the University of Alberta and I was hooked.

Huge skull of a Shonisaurus overlooks the cast of a ichthyosaur skull from Queensland Museum. Image Andrew Frolows/ANMM

The course gave me a good overview of the topic – I now understand the difference between a pliosaur and a plesiosaur (the first is a type of the second) – and it helped me find a framework for the exhibition content. The latter was crucial, as it’s a vast field stretching across hundreds of millions of years, with countless approaches and directions that an exhibition could follow. I decided to focus on the three main groups of marine reptiles: ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs and mosasaurs.

Even with a framework in place, there’s a lot to consider. For example, do we want to show model reconstructions of the creatures, or just bones and animations? Real fossils or replicas? Australian species or ones from overseas? Do we include specimens of the whole ecosystem or just the marine reptiles? How scary? How high-tech? How do we make it different to prehistoric shows in other museums?

Finding fossils

Luckily, Queensland Museum came on board as exhibition partners, giving us access to their palaeontologists and extensive fossil collection. I spent many happy hours exploring their immense stores with Senior Curator of Palaeontology Dr Espen Knutsen, finding specimens for the exhibition and brainstorming content ideas. I also contacted scientists, museums and universities around the world, hunting for fossils, casts, objects and images we could use to tell our stories.

Some of the things I wanted didn’t exist (and not just because most of the marine reptiles are extinct), so I commissioned various artists and artisans to make what I needed. These creations and their creators were as fascinating as the creatures they depicted, so I decided to include their stories in the exhibition too. As well as telling you what a particular model or object is, the labels also note who made it and how.

Cutting-edge creations

We also took advantage of new techniques and technologies to create models and reproductions of these prehistoric predators. This included using photogrammetry to produce 3D models of specimens without having to cast them, sculpting in Virtual Reality (VR) and 3D printing in ‘stone’.

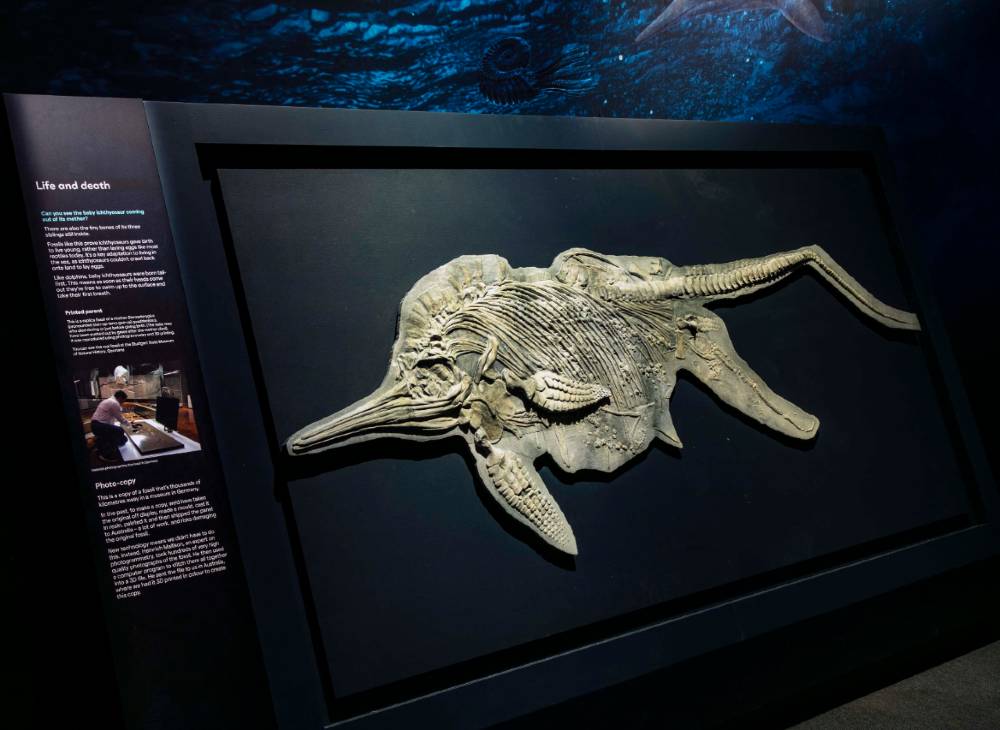

A key specimen I wanted to include is a stunning fossilised ichthyosaur on display in Stuttgart, Germany. Preserved with her baby emerging tail-first from inside her, it serves us irrefutable evidence that these creatures gave birth to live young – unlike most land-based reptiles, which lay eggs. The specimen was not available for loan however, and creating a mould, casting it , and then shipping the replica would have been very expensive, and risked damaging the original.

Fortunately for us, Dr Heinrich Mallison, who is also located in Germany, was able to help. Heinrich is an expert in photogrammetry, a technique where you photograph specimens, centimetre by centimetre, and then use specialist software to convert the hundreds of pictures into accurate and detailed 3D digital models. Heinrich photographed the Stuttgart specimen and sent us the file, which we had 3D-printed in a stone-like material to form a stunning reproduction that shows all the intricate details, and is even robust enough to touch. Photogrammetry and similar techniques are revolutionising palaeontology, as they allow scientists to study fossils from all over the world without having to travel.

3D-print of the Stuttgart specimen and the label showing how it was made. Image Andrew Frolows/ANMM

Scientists are also using 3D models and printing for different areas of research. One story included in the Sea Monsters exhibition features Dr Luke Muscutt from the University of Southampton, UK, who used 3D-printed plesiosaur paddles in flow tanks to look at their unique swimming motion. Plesiosaurs are the only known creatures ever to swim by flapping all four of their flippers (turtles only flap their front ones). Luke’s research led another group to apply this very efficient four-flipper motion to an underwater robot, creating an incredibly manoeuvrable machine.

Kid curators

I basically became a complete bore about these incredible creatures. When anyone casually asked, ‘How’s work?’, they could expect to get a list of all the wonderful things I’d discovered. Luckily, most listeners seemed to become similarly hooked by my tales, so I thought it would be good to know what others found particularly interesting. Did the same cool facts that awed me grab them, or were there other aspects that took their fancy?

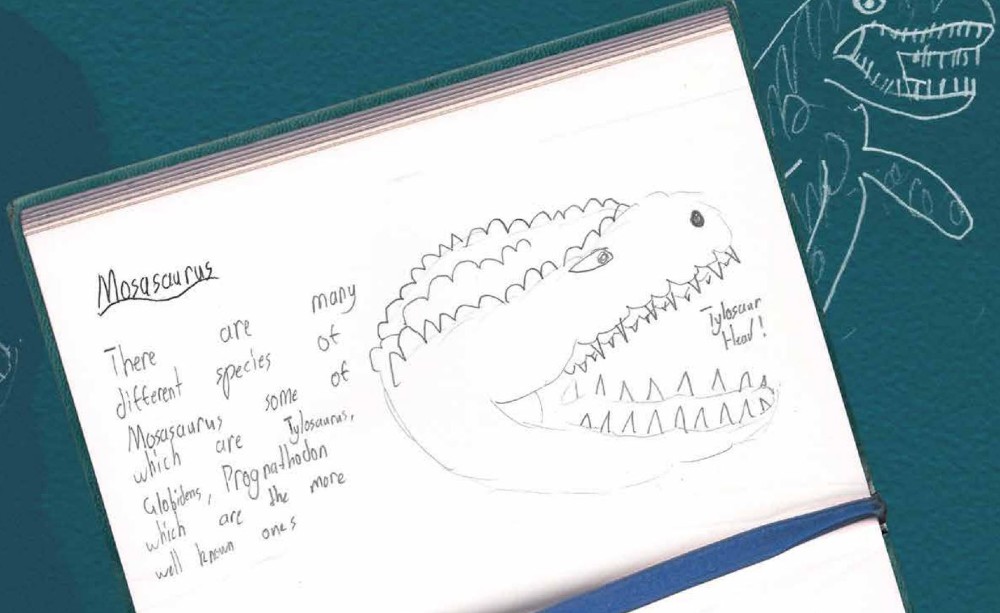

Contributions by the kid curators are displayed in drawers throughout the exhibition. Drawings and notes by Kai'zen Leggett, design by Hawke Graphics. ANMM image

I was especially interested to see which elements appealed to kids, as they would make up a large part of our audience. So I asked some. I talked to them about the exhibition and my research, showed them some books and asked what they thought. They thought it was pretty cool – so cool, in fact, that they started doing their own research and sent me wonderful drawings and sketches of their favourite creatures. Their work was fabulous, funny and far too good not to share, so we decided to add the work of these ‘kid curators’ to the exhibition, giving a younger viewpoint on these ancient animals.

An awesome experience

Ancient marine reptiles were discovered before the first dinosaur fossils and have fascinated us ever since. I’ve loved the process of getting to know them. I’ve learnt from scientists, research papers, websites and reference books, and also gained alternative perspectives from others involved in the exhibition: how a model-maker researched a sea snake’s stripes to paint his plesiosaur, or how a composer listened to today’s ocean creatures to inspire his gallery soundscape. Nine-year-old Ki’lulu, one of our kid curators, said, ‘I loved helping with the exhibition and it was an awesome experience for me.’ I would have to agree.

Our sea monsters will be at the museum until April 2020 – come and meet them. Plus there’s plenty more stories and behind-the-scenes content to be explored.

Created in partnership with