![Workers place concrete reinforcement steel in the Tooma–Tumut Tunnel, part of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme, 1960. Photographer Don Edwards. ANMM Collection Gift from Barbara Alysen ANMS0215[016] Workers place concrete reinforcement steel in the Tooma–Tumut Tunnel, part of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme, 1960. Photographer Don Edwards. ANMM Collection Gift from Barbara Alysen ANMS0215[016]](/-/media/anmm/images/blog-content/2019/10-oct-2019/anms0215016_2160x1080-copy.jpg?h=960&la=en&mw=1920&w=1920)

Seventy years ago today, the first blast was fired in the town of Adaminaby in southern New South Wales, officially marking the start of construction on Australia’s largest engineering project – the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme.

The 70th anniversary of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme

Seventy years ago today, work began on Australia’s largest engineering project – the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. This project was designed to divert water from the Snowy River and some of its tributaries, westward through the Great Dividing Range, to provide irrigation water and generate hydro-electric power. It is often regarded as the birthplace of multicultural Australia, as two-thirds of the 100,000-strong workforce were immigrants. With the names of nearly 700 Snowy workers inscribed on the museum’s Welcome Wall, I thought it would be timely to showcase some of their Snowy stories.

Between 1949 and 1974, the Snowy scheme employed immigrants from 32 countries. Many had endured the hardships of World War II in Europe. Yugoslav miner Nikola Brbot fled the Communist dictatorship after the confiscation of his land and livelihood. He escaped across the Slovenian mountains into Austria and eventually to Australia, where he worked in the pine forests of South Australia before joining the Snowy scheme.

Russian-born Alexander Sariban studied engineering in Germany and worked on the Snowy in the early 1960s. He was married to Olga Popov, whose family had fled from Ukraine to Germany at the height of the Russian Revolution. Olga was a manicurist in a Berlin salon, where her clientele included the German actress Marlene Dietrich. Other Snowy workers inscribed on the Welcome Wall, such as Italian labourer Bruno Caridi and Spanish fitter Roman Torres, settled in Australia first and later married proxy brides in their homeland.

Group of migrants on the deck of MV Napoli, 1951. Many went to work on the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. ANMM Collection Gift from Davide Ellero 00003536

Snowy scheme and Australian dreams

The Snowy scheme realised the great Australian dream of harnessing water from the mountains to irrigate the Murray and Murrumbidgee areas. This required the construction of a complex system of dams, tunnels, aqueducts and power stations. The work was physically demanding and dangerous (121 workers died during the project), and living conditions in the temporary camps were primitive.

Some workers had been specifically recruited to support the scheme, such as German plumber Karl Schmidt. He was one of 800 tradesmen from the cities of Hamburg, Berlin and Hanover, who signed a two-year labour contract in Germany in 1951. Karl notes that they shifted, erected and maintained all the towns, camps and snow huts throughout the scheme.

Meanwhile Dutch carpenter Cornelis Lokker worked as a hawker in the Snowy, driving his van to the camps to sell clothing. He was later joined by his wife Maria and daughter Jannigje, and the family went on to operate a general store in the town of Adaminaby.

Many workers came to the Snowy scheme from seasonal cane-cutting jobs in north Queensland. Radomir Djurovic, a Montenegrin army officer, had survived the horrors of war in Yugoslavia and emigrated from Egypt in 1948 with his wife Milka Petkovic and baby son. Croatian-born Milka was a cleaner and waitress at the scheme headquarters and served Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip during their Snowy visit. Radomir was a truck driver on the scheme and was proud to be able to purchase a piano accordion, bicycle and refrigerator through his hard work.

Others still left it to fate. Czechoslovakian electrical engineer Paul Silink emigrated from Java in 1950 with his wife Vera and two sons. Their future was decided on the toss of a coin – heads for Texas and tails for Australia. Australia it was.

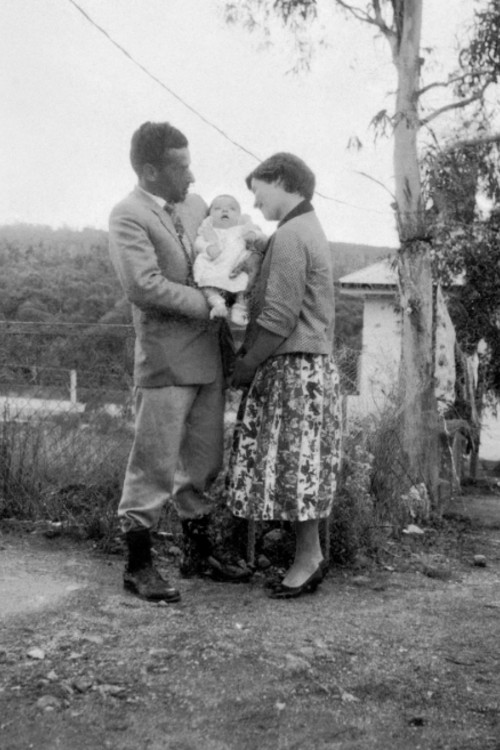

José and Maria Coelho with their newborn son John in Cooma, New South Wales, 1958. Reproduced courtesy Rose Hills

Many who headed to the Snowy Mountains would find the climate inhospitable. José and Maria Coelho had traded sunny Madeira Island in Portugal for the freezing cold of the Snowy. Every morning, Maria would wake to find her newborn son John’s nappies frozen on the washing line. But for others, such as the Norwegian Nilsen-Hepsoe family who arrived in Cooma in the 1950s, it was wonderful – ‘just like Norway, snow in winter’.

English diesel fitter Dennis Beard had heard about the Snowy scheme after arriving in Melbourne and remembers, ‘Men from all nations worked in harmony in appalling conditions. Sleeping in tents, no water, heating, radio or papers. Yet I enjoyed every minute, the great outdoors, wonderful companions, wonderful memories’.

Cypriot motor mechanic Ypsilandis Koulaouzos arrived in Australia with just £10 in his pocket and worked on the Snowy before building a successful business in Sydney. His son says that like the Peter Allen song, Ypsilandis always called Australia ‘home’. Meanwhile the daughters of Polish carpenter Florian Biniak recall, ‘He always talked about his involvement with the Snowy from 1953 – the mateship with others, the beautiful country of Bonegilla, Cooma, Manuka, Lake Jindabyne and Eucumbene’. He was immensely proud of the part he played in the Australian dream.

![Workers place concrete reinforcement steel in the Tooma–Tumut Tunnel, part of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme, 1960. Photographer Don Edwards. ANMM Collection Gift from Barbara Alysen ANMS0215[016]](/-/media/anmm/images/blog-content/2019/10-oct-2019/workers-place-concrete-reinforcement-steel-in-the-toomatumut-tunnel-part-of-the-snowy-mountains-hydr.jpg?la=en)

Workers place concrete reinforcement steel in the Tooma–Tumut Tunnel, part of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme, 1960. Photographer Don Edwards. ANMM Collection Gift from Barbara Alysen ANMS0215[016]

Realising the dream

When completed in 1974, the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme comprised seven power stations, 16 dams, 145 kilometres of tunnels and 80 kilometres of aqueducts. Some workers, such as Italian farmer Antonio Diamante, had remained with the scheme for the entire 25 years of its construction. He was employed at a number of locations including Khancoban, Geehi Dam, Talbingo and Tumut 3 Power Station.

Others celebrated with world records – Norwegian miner Arild Sverdrupsen was part of a team that set a mining record on the Eucumbene–Tumut tunnel in 1954, while Italians Dario Sain and Joe Maier were awarded medals for another tunnelling record in 1959.

Many Snowy workers would contribute to major building projects in Sydney, including the Sydney Opera House, Sydney Airport, AMP Centre, Darling Harbour and MLC Centre. Italian lumberjack Giovanni Maccagnan worked on the Harry Seidler-designed MLC Centre in Martin Place. His son notes, ‘His story is of a typical migrant with no English and with nothing, yet he became Australian, raised a family and contributed to the nation’s growth. His landmarks will remain on the land’.

Today the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme provides nearly one-third of all renewable energy for the eastern mainland grid, powering the rush hours of Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne. Giovanni Maccagnan and his fellow Snowy workers have certainly left their mark on Australia.