Seventy years ago this October, work began on Australia’s largest engineering project – the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. Curator Kim Tao shares the story of Portuguese newlyweds José and Maria Coelho, who swapped sunny Madeira Island for the isolation of the Snowy Mountains.

On 17 October 1949, the first blast was fired in the town of Adaminaby in southern New South Wales, signalling the start of construction on the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. This ambitious project was designed to divert water from the Snowy River and some of its tributaries, westward through the Great Dividing Range, to provide irrigation water and generate hydro-electric power. The Snowy scheme employed more than 100,000 people over a 25-year period and is often regarded as the birthplace of multicultural Australia. Two thirds of the workforce were either displaced persons or assisted immigrants from 32 countries, including Britain, Germany, Italy, Poland, Russia, Norway, Yugoslavia and Portugal.

José Cristino Fernandes Coelho (1925–2019) emigrated from the island of Madeira, an autonomous region of Portugal situated in the North Atlantic Ocean, known for its mild climate. He was born and raised in a farming family in Lombo das Terças, in the coastal village of Ponta do Sol (meaning ‘Point of the Sun’). As a teenager, José was awarded a scholarship to study Latin, mathematics and religious studies at the Franciscan Mission School Montariol, located in the ancient city of Braga in northern Portugal. This instilled in him a lifelong love of learning and teaching, and he went on to run a small primary school in Ponta do Sol. In August 1956, José married Boaventura-born nurse Maria Amélia Andrade (1932–2015) in Funchal, the capital of Madeira.

Shortly after their August wedding, José embarked for Sydney from the port of Funchal. Maria would follow eight months later, once her husband had established himself. With a suitcase each and hearts filled with hope, the newlyweds endured many hardships in migrating to Australia. José travelled on the Compagnie des Messageries Maritimes cargo–passenger ship Calédonien, which operated regularly between France and its island outposts in the Caribbean and the Pacific. The vessel sailed via the Panama Canal and made port calls in Fort-de- France, Pointe-à-Pitre, Papeete, Port Vila and Nouméa. While in Papeete, Tahiti, José was surprised to find a very important passenger on board – French general Charles de Gaulle, leader of the French Resistance during World War II, and later President of the French Republic.

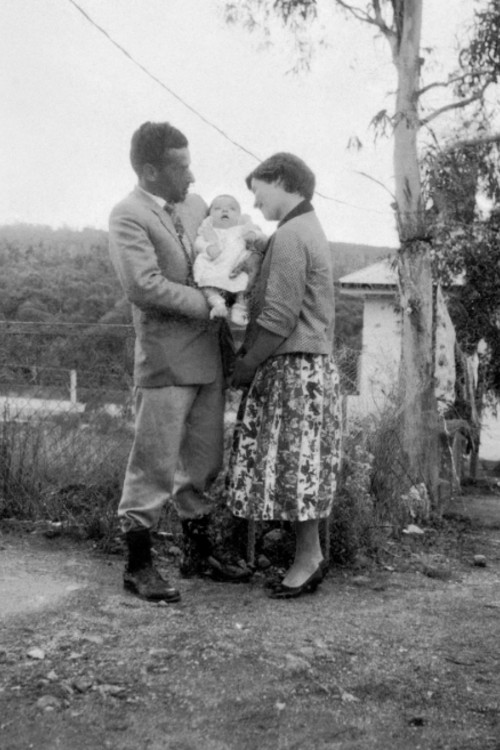

Maria and José Coelho on their wedding day in Funchal, Madeira, 1956. Reproduced courtesy Rose Hills

José took several photographs of de Gaulle in Tahiti, including one showing the general in conversation with a Catholic priest, and another one of him delivering a speech. On the back of the latter photograph, an impressed José wrote: ‘de Gaulle giving a speech about freedom without pomp and ceremony and without chairs’. José respected the humble leadership qualities displayed by de Gaulle during the Second World War, particularly as Portugal had suffered harshly under the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar since the 1930s. For José, migrating to Australia was as much about political freedom as it was about finding the sort of leadership he admired in Charles de Gaulle.

José docked at Sydney’s Woolloomooloo wharf on Calédonien in September 1956, while Maria arrived in Sydney aboard a Qantas flight in May 1957. Twenty-four-year-old Maria, who did not speak any English, had bravely travelled on her own from Portugal. Among her possessions was an unsent postcard of Rome, on which she had written a few lines to her new husband, as well as the word ‘Bangkok’ – likely to have been a refuelling stop for the Qantas VH-EAN aircraft.

José and Maria’s early years in Australia were incredibly challenging. Their first accommodation in Sydney was a small share house in inner-city Darlinghurst, where they had to contend with bedbugs and the loss of their privacy. José found work as a labourer with Utah Construction at St Marys in Sydney’s west, and then as a labourer at the University of Sydney.

In January 1958, José and Maria moved to the town of Cooma, some 100 kilometres south of Canberra. José worked as a labourer on the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme, based at Island Bend – one of the 16 major dams built for the Snowy scheme, along with seven power stations, 145 kilometres of tunnels and 80 kilometres of aqueducts. The work was physically demanding, dirty and dangerous (121 workers died during the construction between 1949 and 1974), and the climate inhospitable. Living conditions in the temporary camps were primitive. José and Maria had very little money and they could only afford to live in a caravan in Cooma. Maria, who was by then expecting her first child, got a job as a nurse at a small clinic in the town. She was forced to stop working in the later stages of her pregnancy, as she was no longer able to lift her patients.

Maria and José had traded the temperate climate of Madeira for the freezing cold of the Snowy, but they were in search of a new life

In the winter of 1958, Maria gave birth to a son, John Cristino, at Cooma Hospital. John was one of more than 500 babies born in Cooma that year – a record number that was attributed to the beginnings of the Snowy scheme. Every morning, Maria would wake to find her newborn son’s nappies frozen on the washing line. She and José had traded the temperate climate of Madeira for the freezing cold of the Snowy, but they were in search of a new life. There was no doubt that these difficulties inspired their dream of having their own home.

José and Maria Coelho with their newborn son John in Cooma, New South Wales, 1958. Reproduced courtesy Rose Hills

Although José was grateful to have secured employment on the Snowy scheme (which by 1959 had reached its peak workforce of 7,300), he found the manual labour to be demoralising. His greatest passion was teaching, fostered during his scholarship with the Franciscan monks in Portugal. After a year in Cooma, José and Maria decided to return to Sydney with baby John. In Sydney, Maria gave birth to a daughter named Rose in 1960, while José found work as a community Portuguese language teacher at St Peter’s Church in the inner-city suburb of Surry Hills.

The Snowy scheme employed more than 100,000 people over a 25-year period and is often regarded as the birthplace of multicultural Australia

José and Maria worked hard to put down a deposit on a small terrace house on Phillip Street in Waterloo, then considered a slum suburb bordering working-class Redfern. The area was known for its Indigenous history and this led to a painful encounter with racism and the vestiges of the White Australia policy. While Maria had a fair complexion, José was dark-skinned. One day, after they had moved into their Waterloo terrace, the police knocked on the door and asked Maria, ‘Why are you [a white woman] living with a black man?’ This incident served to further undermine José’s already fragile sense of belonging.

José and Maria endeavoured to give their two children, John and Rose, a better life. Despite their educated backgrounds in Madeira, they took on various menial jobs in Australia – Maria as a cleaner juggling three shifts per day, and José as a labourer, tram conductor, delivery truck driver and taxi driver. In 1967 they finally earned enough money to buy their beloved house in the Sydney suburb of Rosebery. The family relocated there after the state government instigated its slum clearance scheme in Waterloo in the 1960s, during which historic terrace houses were replaced with new high-rise public housing.

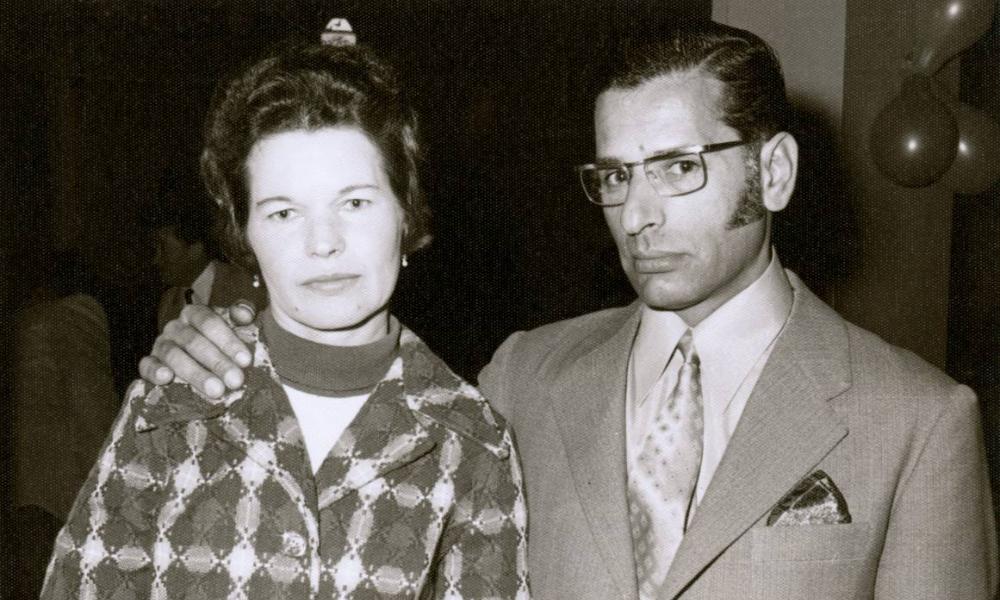

Maria and José Coelho in Sydney, 1970s. Reproduced courtesy Rose Hills

In the 1980s, when Maria was in her 50s, she started running marathons and playing the flute. She enjoyed these hobbies until a chronic lung condition (bronchiectasis related to exposure to tuberculosis) took hold. Maria had contracted the disease while working as a nurse in Funchal. Nevertheless, in her 70s, she acquired a busking permit from Sydney’s Waverley Council and performed at Oxford Street Mall in Bondi Junction. Maria was a strong and compassionate woman, and always appreciated the fact that she could pursue hobbies that might not have been possible had she lived all of her life on Madeira Island. She eagerly embraced the outdoor lifestyle of Australia, while also preserving the best of her own culture – the Portuguese language, Catholic faith and the emphasis on family.

In the 1980s, Maria helped to put José through the University of Sydney. He gained his teaching qualifications and achieved his dream of becoming a primary school teacher. Maria and José also encouraged their two children to obtain tertiary qualifications. Their daughter Rose studied arts and law at the University of New South Wales and became an artist, while their son John graduated with a degree in electrical engineering from the University of Technology Sydney and became an electrical engineer. Sadly, John died of leukaemia in 2001, aged 41. Maria Coelho died of bronchiectasis in 2015, aged 83.

Reflecting on her family’s life in Australia, Rose Hills (née Coelho) says:

I had great parents who suffered many losses, leaving family behind in Madeira and not being able to afford expensive plane fares to return until the mid-1980s. They lost part of their identity and lost their only son. What lives on in me is the love of Portuguese music and language [José started teaching Rose in 2005, when he was diagnosed with sarcoma. He died in May 2019, aged 93]. Most of all they encouraged and supported me to get three university degrees. They were fantastic grandparents to my children, making up for my own lonely childhood when John and I were left home alone before and after school, so that they could work unqualified shift jobs.

Rose registered her parents’ names on the Welcome Wall to acknowledge their love and selfless sacrifice, and to honour their memory for her two sons.

The Welcome Wall

For 20 years, the Welcome Wall at Pyrmont Bay Wharf has celebrated and recorded the stories of those who left their native shores to make Australia home. Honour your family's migration heritage by including an inscription on the Welcome Wall.

This article originally appeared in Signals magazine (Issue 128).