Dirk Hartog

Dirk Hartog was born in Amsterdam in 1580, the second son of Hartych Krijnen, a mariner, and Griet Jans. In February 1611, Hartog married 18-year-old Meynsgen Abels at Amsterdam’s Oude Kerk (Old Church), the same church in which he was baptised. It is not known whether the couple had any children.

Before joining the VOC in 1615, Hartog traded as a private merchant and skippered the small vessel Dolphyn (Dolphin) to a number of Baltic and Mediterranean ports. In January 1616, aged 35, he became the skipper of the 700-tonne Eendracht on its maiden voyage to Bantam in the East Indies. The ship embarked from Texel in North Holland along with four other vessels. It had a crew of 200 and carried 10 money chests containing 80,000 reales (pieces of eight), valued at about 200,000 guilders, which were to be delivered to VOC trading posts in the East Indies.1

Hartog saw ‘several islands, though uninhabited’, behind which a vast mainland could be seen.

In August 1616 Eendracht arrived at the Cape of Good Hope alone, after becoming separated from the fleet during a storm. It was restocked with supplies of fresh fruit, vegetables and drinking water, before departing the Cape three weeks later following the new Brouwer route. Eendracht sailed too far east, however, resulting in an unexpected encounter with the then unknown west coast of Australia, where Hartog saw ‘several islands, though uninhabited’, behind which a vast mainland could be seen.2

Cape Inscription, Dirk Hartog Island

On 25 October 1616, Eendracht made landfall at the northern end of Dirk Hartog Island in Shark Bay, an area that was home to the Malgana people. Hartog and his crew spent two days ashore. The group examined the area thoroughly but determined that it held nothing of apparent commercial value. Before proceeding for Bantam on 27 October, they inscribed a testimony of their visit on a flattened pewter dinner plate.

Dirk Hartog plate, 1616. Tin (metal), 36.5 cm (diameter). Reproduced courtesy Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Recording their landing date, the name of the ship and its senior crew, and details of the onward journey, this act transformed an ephemeral engagement into a tangible mark of discovery. The Hartog plate was nailed to an oak post placed on the rocky cliff top, overlooking what is now known as Cape Inscription. The message on the plate is translated as:

1616, 25 October, is here arrived the ship the Eendracht of Amsterdam, the upper-merchant Gillis Miebais of Liege, skipper Dirck Hatichs of Amsterdam; the 27th ditto set sail again for Bantam, the under-merchant Jan Stins, the upper-steersman Pieter Dookes van Bill, Anno 1616.

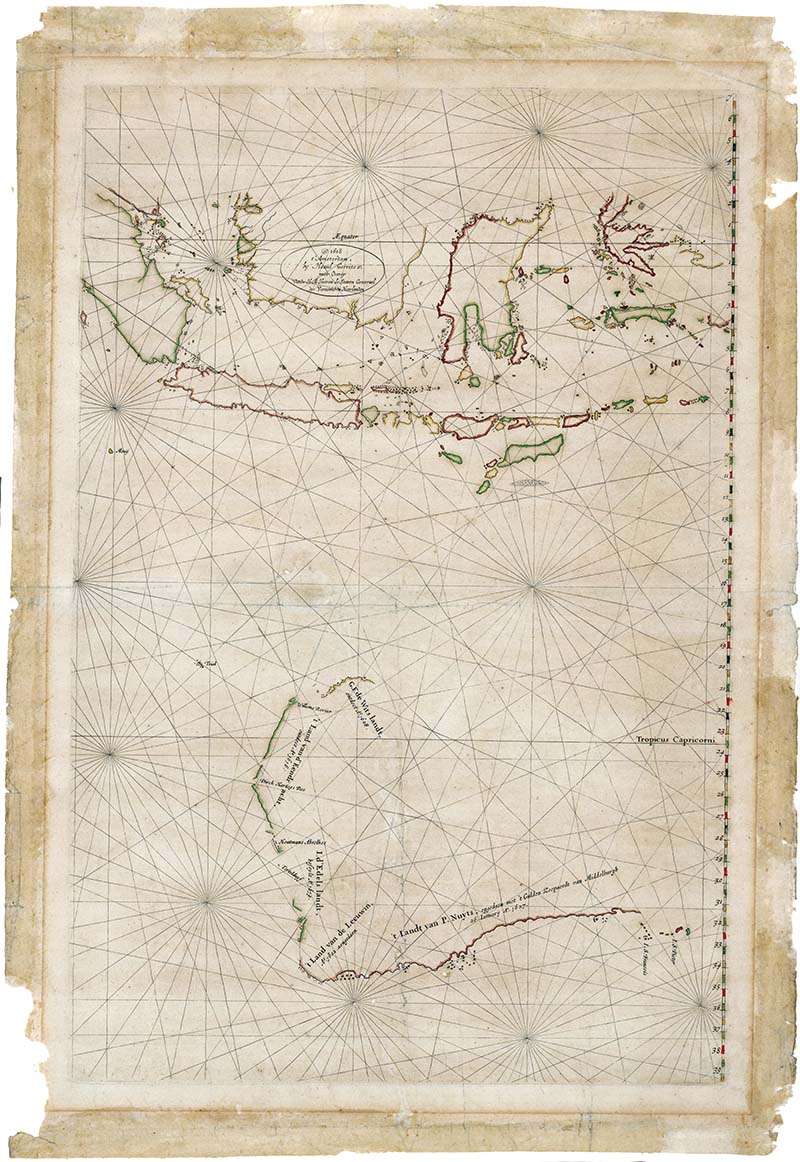

Hessel Gerritsz, Chart of the Malay Archipelago and the Dutch discoveries in Australia, 1618–1628.Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

In December 1616, Eendracht reached Macassar, where 16 of its crew were killed in a confrontation with locals.3 Hartog then visited a number of trading posts to deliver the money chests, before departing Bantam one year later for the return passage to the Netherlands, arriving in the province of Zeeland in October 1618.

Following his history-making voyage, Hartog left the employment of the VOC and became the skipper of Geluckige Leeu (Lucky Lion), which sailed to various European ports. Dirk Hartog died in 1621, shortly before reaching the age of 41, and was buried in the grounds of the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) in Amsterdam. The Eendracht, which embarked on a second voyage to the East Indies in May 1619, was eventually wrecked off the west coast of Ambon Island in May 1622. The wreck site has not been located.

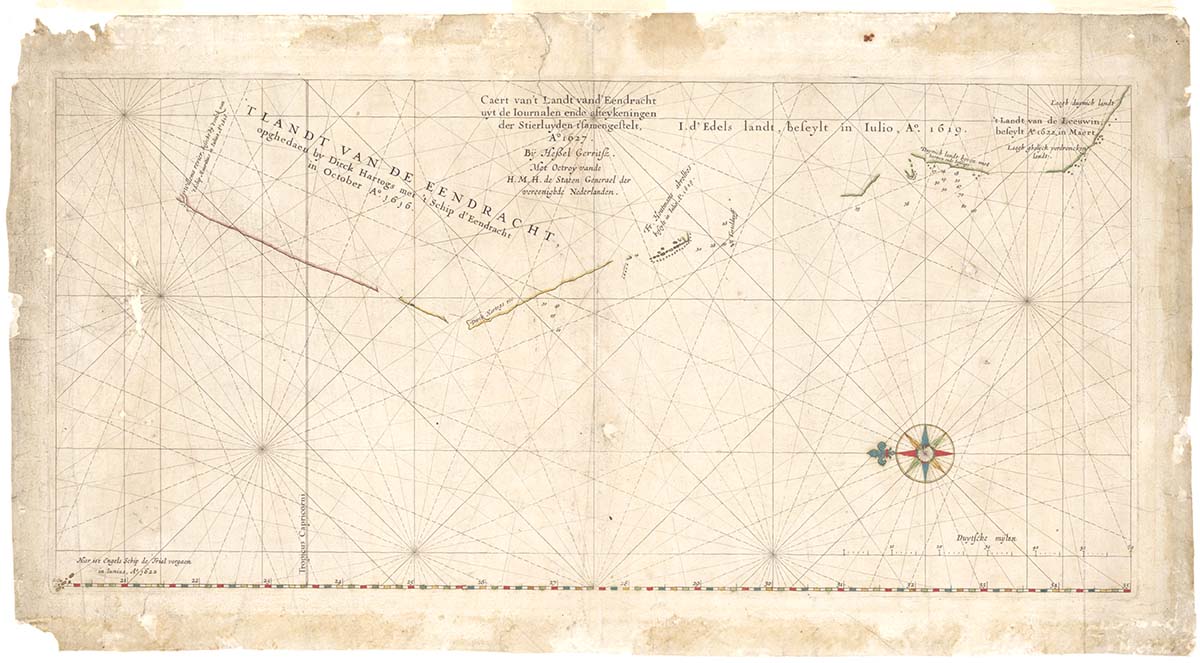

Hessel Gerritsz, Caert van’t Landt van d’Eendracht uyt de Iournalen ende afteykeningen der Stierluyden t’samengestelt (Chart of the Land of the Eendracht), 1627. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

The Land of the Eendracht

Hartog’s landing in 1616 had a significant impact on world geography and cartography, and foreshadowed a series of Dutch, British and French expeditions that would gradually, over the course of two centuries, put Australia on the map. As he sailed north from Shark Bay to Bantam, Hartog charted some 400 kilometres of the Western Australian coastline and named it after his ship, ’t Landt van de Eendracht (the Land of the Eendracht) or Eendrachtsland. This name soon began to appear on maps of the world, in place of the mythical Terra Australis Incognita. Among the earliest were the 1618 and 1627 outline charts by chief VOC cartographer Hessel Gerritsz.

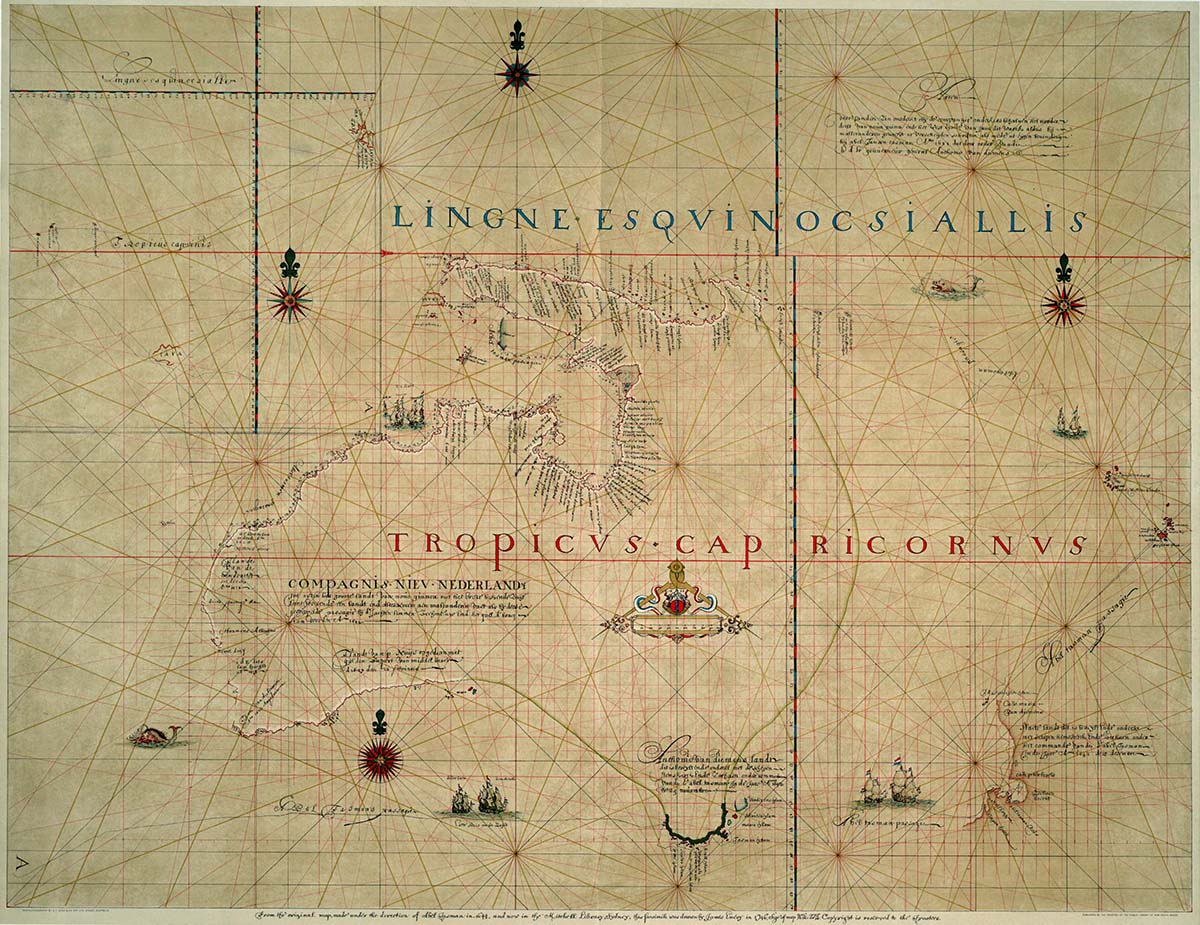

Successive Dutch navigators, including Abel Tasman and Willem de Vlamingh, would extend the charts of the western, northern and southern coasts to give shape to Hartog’s Eendrachtsland, which was also known as ’t Zuyd Landt (the South Land) or ’t Grote Zuyd Landt (the Great South Land). In 1642 Tasman sighted new land that he called Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) after the Governor-General of the East Indies, Anthony van Diemen. In 1644 he completed charting a long stretch of northern coast from the Gulf of Carpentaria to North West Cape, connecting all the unfolding Dutch discoveries to form HollandiaNova (New Holland). Tasman’s two voyages were the last major explorations of New Holland for some decades.

Australia and New Zealand, from the original map made under the direction of Abel Tasman in 1644 and now in the Mitchell Library, Sydney. Facsimile drawn by James Emery in 1946. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

Australia and New Zealand, from the original map made under the direction of Abel Tasman in 1644 and now in the Mitchell Library, Sydney. Facsimile drawn by James Emery in 1946. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

Proof of daring VOC ancestors

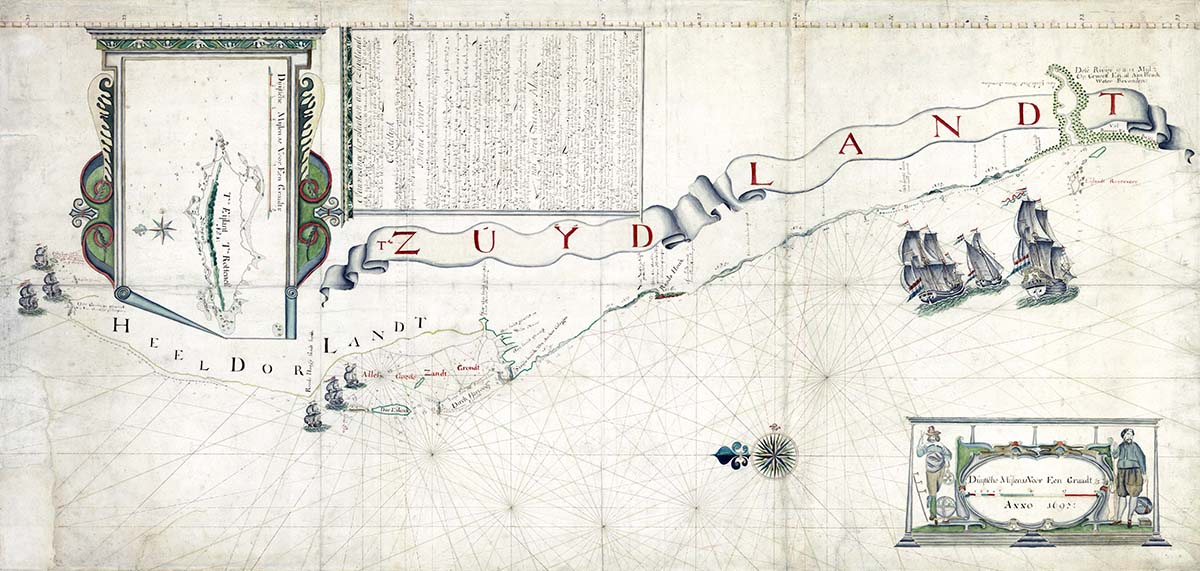

Dirk Hartog’s plate would lie undisturbed at its windswept island outpost for more than 80 years, until Willem de Vlamingh’s expedition in the ships Geelvinck (Yellow Finch), Nyptangh and Weseltje in 1696. De Vlamingh had been instructed to search for possible survivors from the wrecks of two VOC ships, Ridderschap van Holland (lost 1694) and Vergulde Draeck (Gilt Dragon, lost 1656), and also to chart the remainder of the western coast of New Holland. While he was unable to locate any trace of the missing ships, his expedition resulted in the mapping of nearly 1,500 kilometres of coastline, as well as the naming of Rottnest Island, the Swan River and Steep Point, the most westerly point of Australia.

Portrait of a Dutch navigator (believed to be Willem de Vlamingh), attributed to Jan Verkolje and Nicholas Verkolje, c 1690. ANMM Collection 00019487.

In February 1697, de Vlamingh and his crew landed at Dirk Hartog Island and by sheer coincidence discovered the inscribed Hartog plate, lying half-buried in the sand beside its now decayed oak post. Recognising its historic significance, de Vlamingh took the Hartog plate on board and replaced it with a new one engraved with his predecessor’s original message, as well as a record of his own visit. The plate was nailed to a new post of cypress pine collected from Rottnest Island. The inscription on the de Vlamingh plate is translated as:

1697, the 4 February, is here arrived the ship Geelvinck of Amsterdam; the commander and skipper Willem de Vlamingh of Vlieland, assistant Joannes Bremer of Copenhagen, upper-steersman Michil Bloem of the diocese of Bremen. The hooker the Nyptangh, skipper Gerrit Colaart of Amsterdam, assistant Theodoris Heirmans of the same, upper-steersman Gerrit Geritsen of Bremen. The galliot, the Weseltje, skipper Cornelis de Vlamingh of Vlieland, steersman Coert Gerritsen of Bremen; and from here set sail with our fleet to explore the Southland with destination Batavia.

Chart of Willem de Vlamingh’s expedition to the South Land, showing Dirk Hartog Island and the ships Geelvinck, Nyptangh and Weseltje, 1697. The inscription schootel gevonden refers to the ‘dish found’. Reproduced courtesy National Archives of the Netherlands.

In March 1697 de Vlamingh delivered Dirk Hartog’s plate to Batavia as ‘proof of the daring spirit of his ancestors’.4 The following year the plate was taken to the VOC headquarters, East India House, in Amsterdam, where it remained until the company was dissolved in 1799. In 1819 the plate was handed to the Koninklijk Kabinet van Zeldzaamheden (Royal Cabinet of Curiosities) in The Hague, which became part of the Rijksmuseum in 1883. Today it endures as a powerful icon of shared cultural heritage, symbolising the longstanding maritime connections between the Netherlands and Australia. In 1991 Dirk Hartog Island was included in the Shark Bay World Heritage Area, in recognition of its outstanding natural universal values, while the Cape Inscription area was added to Australia’s National Heritage List in 2006 as a place of national significance.

The de Vlamingh plate has been in the collection of the Western Australian Maritime Museum in Fremantle since 1950. It was discovered by French Captain Emmanuel Hamelin of Naturaliste (part of Nicolas Baudin’s expedition) in 1801, and then recovered from the sands of time in 1818 by the French explorer Louis de Freycinet, who presented it to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in Paris. The plate was rediscovered in 1940 and returned to Australia by the French government in 1947. It is one of the few material reminders of pre-British, 17th-century Dutch encounters with the continent that would come to be known as Australia.

The Dutch ultimately abandoned their interest in New Holland in the mid-18th century, having found nothing of commercial value in what they deemed a barren and inhospitable land. In 1770 the British navigator Lieutenant James Cook charted the elusive east coast of New Holland and named it New South Wales. In 1801–1803, Matthew Flinders’ circumnavigation showed that Terra Australis was an island, and not part of a larger southern landmass. Hartog’s Eendrachtsland, New Holland and the Great South Land were finally revealed to be one continent – Australia.

References

- Phillip E Playford, ‘Hartog, Dirk (1580–1621)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- J P Sigmond and L H Zuiderbaan, Dutch Discoveries of Australia: Shipwrecks, Treasures and Early Voyages off the West Coast, Batavian Lion, Amsterdam, 1995, p 36.

- Although Bantam is listed as the onward destination on the Hartog plate, VOC log books indicate Eendracht visited the Dutch factory at Macassar before sailing on to Banda and Bantam. See Western Australian Museum, ‘1616: Dirk Hartog’.

- Peter Sigmond, ‘Cultural Heritage and a Piece of Pewter’, in, Lindsey Shaw and Wendy Wilkins, eds, Dutch Connections: 400 Years of Australian-Dutch Maritime Links 1606–2006, Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney, 2006, p 83.

Credits

Images

Images reproduced courtesy Australian National Maritime Museum. Additional images are reproduced courtesy of Department of Environment, National Archives of the Netherlands, National Library of Australia and Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.