Commemorating the 400th anniversary of Dirk Hartog’s landing

Four hundred years ago, Dutch mariner Dirk Hartog (1580–1621) sailed into history when, on 25 October 1616, he made the first documented European landing on the west coast of Australia. But while his legacy is preserved through the remote island that now bears his name at the entrance to Shark Bay, Western Australia, Hartog himself remains an enigmatic figure.

This evocative pewter relic provides tangible evidence of one of the earliest European encounters with the mysterious Terra Australis Incognita – the unknown southern land.

Dirk Hartog landing site 1616 at Cape Inscription, Dirk Hartog Island, Western Australia. Image: Nicola Bryden / © Copyright Department of the Environment.

Dirk Hartog landing site 1616 at Cape Inscription, Dirk Hartog Island, Western Australia. Image: Nicola Bryden / © Copyright Department of the Environment.

There are no known portraits of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (Dutch East India Company) captain or his ship the Eendracht (Concord or Unity). At a period in which regional Dutch spellings were not yet standardised, his forename appears variously in the historical record as Dirck, Dirick or Dierck, and his surname as Hatichs, Hartoogs, Hartogszoon or Hartogh. Regardless of its spelling, four centuries on his name is synonymous with the inscribed ‘Hartog plate’ that marked his landfall at the far western edge of the Australian continent. This evocative pewter relic, now held in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, provides tangible evidence of one of the earliest European encounters with the mysterious Terra Australis Incognita – the unknown southern land.

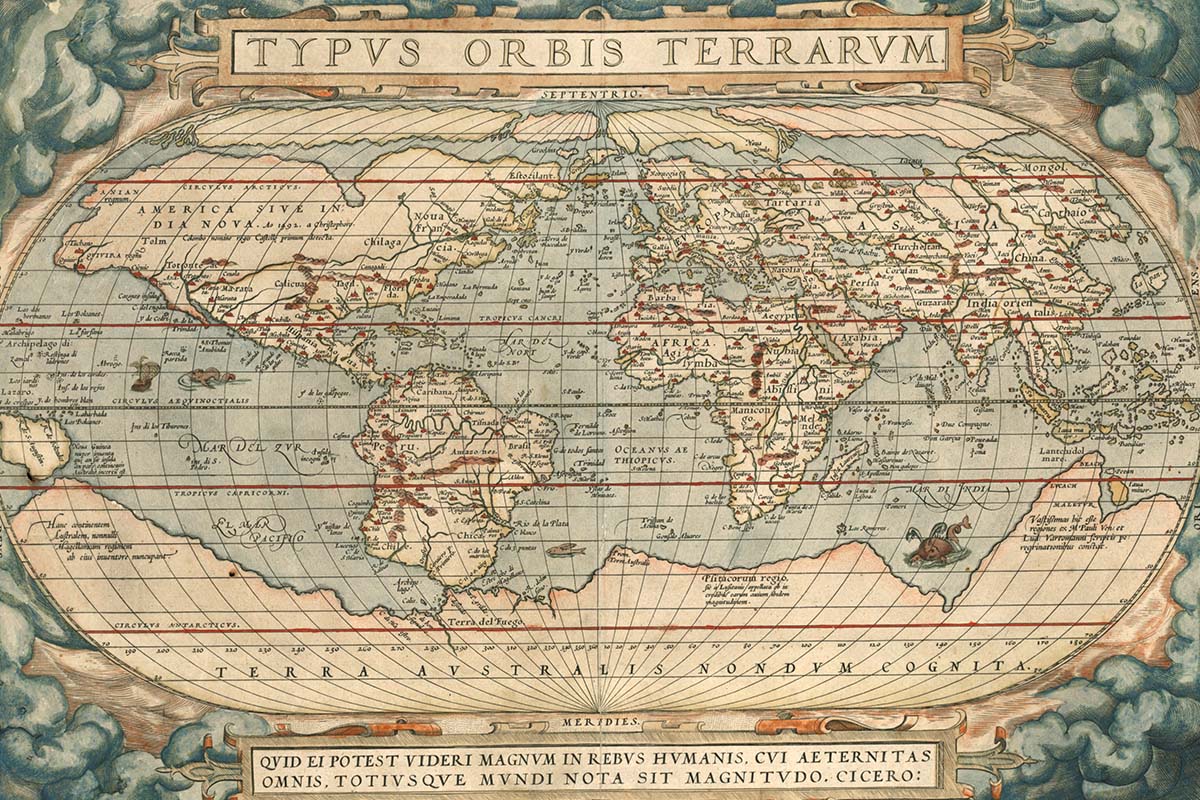

Abraham Ortelius, Typus orbis terrarum, c 1570. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

Abraham Ortelius, Typus orbis terrarum, c 1570. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

Terra Australis Incognita

Ancient Greek and Roman scholars firmly believed in the existence of a southern land, based on the concept of a balanced globe. In the fourth century BC, Greek philosopher Aristotle declared that ‘there must be a region bearing the same relation to the southern pole as the place we live in bears to our pole’, while geographer Ptolemy of Alexandria, in the second century AD, hypothesised that the landmass of the northern hemisphere should be balanced by a similar landmass in the south.1 Their ideas influenced the work of 16th-century cartographers including Gerardus Mercator and Abraham Ortelius, whose world maps depicted fabled southern lands that overflowed with gold and spices, and were derived from the tales of Venetian traveller Marco Polo in the 13th century.

Hendrik Cornelisz, The Return to Amsterdam of the Second Expedition to the East Indies, 1599. Oil on canvas, 102.3 x 218.4 cm. Reproduced courtesy Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Hendrik Cornelisz, The Return to Amsterdam of the Second Expedition to the East Indies, 1599. Oil on canvas, 102.3 x 218.4 cm. Reproduced courtesy Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The promise of gold and abundant wealth lured European voyagers to the southern seas – home to exotic goods such as tea, porcelain, silk and spices. At the end of the 15th century, Portuguese explorers discovered the seaway from Europe to Asia around the southern tip of Africa, and dominated this trade route for a century. But by the end of the 16th century, the Dutch and English were ready to challenge their monopoly. European interests were particularly centred on the historic Spice Islands (the Moluccas) in the eastern part of the Indonesian archipelago, once the world’s exclusive source of nutmeg and cloves. Here traders wrestled for control of the lucrative market in spices, which were in high demand in Europe as they had medicinal qualities, added flavour and zest to food, and also helped in food preservation (this was especially important in the days before refrigeration). It was against this backdrop that the Dutch government formed the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (also known by its Dutch acronym VOC) in 1602.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC)

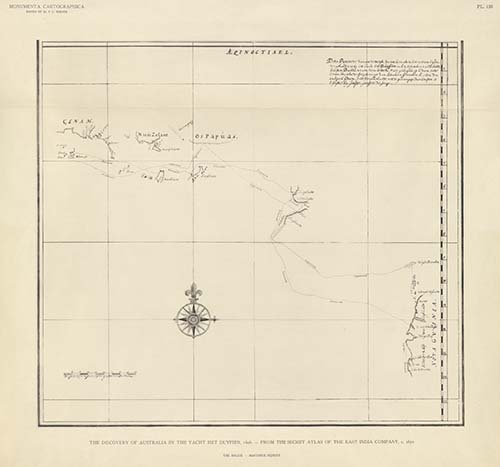

Dese pascaerte vertoont de wegh, soo int heen als in het weerom seylen, die gehouden is bij het jacht Het Duijfien in het besoecken van de lands beoosten Banda, tot aen Nova Guinea (The discovery of Australia by the yacht Het Duyfien, 1606), c 1670. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

The VOC brought together six regional chambers of commerce based in the coastal cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Hoorn, Enkhuizen, Delft and Middelburg, and was governed by a board of directors known as the Heren XVII (Gentlemen 17). Exercising a mix of diplomacy, commercial pressure and military force, it developed into one of the largest and most powerful companies in the world, with fortified trading posts scattered around the coasts of Africa, India and Asia. The VOC’s activities were focused on discovering and exploiting new profitable ventures in the east, as opposed to acquiring territorial possessions. It was in this context that the earliest Dutch engagement with the Australian mainland and its indigenous inhabitants was established, when the VOC’s Willem Jansz, captain of the Duyfken (Little Dove), was sent by the Governor-General at Bantam (now Banten) to explore the legendary island of gold, New Guinea. In early 1606 Jansz charted more than 300 kilometres of the west coast of Cape York Peninsula, but found nothing to recommend it from a mercantile point of view. He was unaware that he had made the first documented European sighting of the unknown southern land, regarding it instead as an extension of New Guinea.

In 1619 the VOC consolidated its position in the East Indies by establishing a permanent base at Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia), following Governor-General Jan Pieterszoon Coen’s conquest of Jacatra. The walled city, crisscrossed by canals reminiscent of Holland, was home to bureaucrats, merchants, mapmakers, soldiers and shipwrights. By 1700 Batavia had a population of about 70,000 people, 6,000 of whom were Europeans. The VOC dominated the commerce of the Far East until it was eclipsed by the British East India Company in the 18th century.

Frederick De Wit, Town plan of Batavia, Java, 1681. ANMM Collection 00003434.

Frederick De Wit, Town plan of Batavia, Java, 1681. ANMM Collection 00003434.

A new route to the East

Matthys Balen, Portrait of Henrik (Hendrik) Brouwer, Governor General of the Dutch East Indies, 1632–1636, 1726. ANMM Collection 00008301.

Between 1595 and 1795, Dutch ships made nearly 4,800 voyages across the Indian Ocean on their way to the Spice Islands, originally taking up to a year to sail one way from Europe to Asia. During this time the protracted journeys, cramped conditions and equatorial heat took their toll on seafarers. In 1610–11 Hendrik Brouwer, commander and later Governor-General of the East Indies, pioneered a faster sea route that utilised the westerly winds of the Southern Ocean between latitudes 35° and 40° south, rather than the more traditional northerly routes across the Indian Ocean. The Brouwer route instructed ships to maintain an easterly course for at least a thousand mijlen (an old Dutch mile, equivalent to approximately four modern nautical miles), or about 7,400 kilometres, after rounding the Cape of Good Hope, before heading north towards the Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java. In doing so VOC ships could halve their sailing time, so reducing the risk of infectious disease and death among the crew, while also giving the company a distinct advantage over its competitors. The Brouwer route was officially adopted by the VOC in its 1617 seynbrief (sailing instruction):

… not only because this route has a wide sea, free of all rocks and shoals, a cooler climate which is healthier for the people and is better to prevent heat and decay of the victuals and the cargo, but also because steady Westerly winds blow here and because the degrees are considerably shorter, so that one makes up for the distance apparently lost in this route by looking for the Westerly winds and having to sail back North again.2

The main navigational problem with the Brouwer route was working out when to turn north. The only orientation points on the way were the small islands of St Paul and Amsterdam at about 700 mijlen. While navigators were able to ascertain their latitude (distance north or south of the equator) by this time, there was no reliable method for determining longitude (distance east or west of a given point) at sea until the development of the marine chronometer in the 18th century. Thus a consequence of the new route was that VOC ships might sooner or later come into contact with the west coast of Australia. The wrecks of a number of VOC ships dotted along the treacherous western seaboard attest to the early Dutch presence in the Indian Ocean, as does a most curious encounter at a prominent, but isolated, headland on Western Australia’s largest island.3 Today it is known as Dirk Hartog Island, named after the first recorded European to set foot on it in October 1616.

Map of the Shark Bay area in Western Australia. Reproduced courtesy Wikimedia.

References

- Aristotle, Meteorology, Book II, Part 5.

- J P Sigmond and L H Zuiderbaan, Dutch Discoveries of Australia: Shipwrecks, Treasures and Early Voyages off the West Coast, Batavian Lion, Amsterdam, 1995, p 33.

- The wrecks include Batavia (1629), Vergulde Draeck (1656), Zuytdorp (1712) and Zeewijk (1727).