Detail of the Gourlay Bros. plan of the Bonnie Dundee. ANMM Collection, 00001118

In 1987 the Australian National Maritime Museum purchased a set of original shipyard plans produced by the Scottish marine engineering and shipbuilding company Gourlay Brothers & Co. in Dundee. Like the best of discoveries, it seems the plans were destined for the rubbish but were saved at the eleventh hour. Together the plans represent images of early Australian cargo vessels, as well as a wide range of Australian shipowners and a long tradition in ship construction procedures.

Gourlay Brothers & Co. was a renowned Dundee company. Henry Gourlay in particular was known as a ‘great mid-Victorian engineer’. His technical skill saw the company excel in marine engines and much of their output was destined for the overseas market.

One plan in this precious collection is a particular favourite—that of the steamer SS Bonnie Dundee. Built in 1877 for the Nicoll Brothers, George and Bruce, the Bonnie Dundee was intended for service in Australia. The plan is noteworthy in showing a very unique artistic flair. The unusual script brings to mind an anonymous and frustrated artist toiling away in a noisy shipyard, the only outlet of his creative talent being in the freedom he was able use to label the technical drawings.

The Bonnie Dundee itself was described as a ‘smart little screw steamer, the machinery appears to have been well and faithfully put together and the steamer is a most sightly and well-proportioned craft’. It sailed from Dundee to Australia in 1877 and was soon a regular on the Sydney to Lismore service as part of the growing Nicoll Brothers fleet.

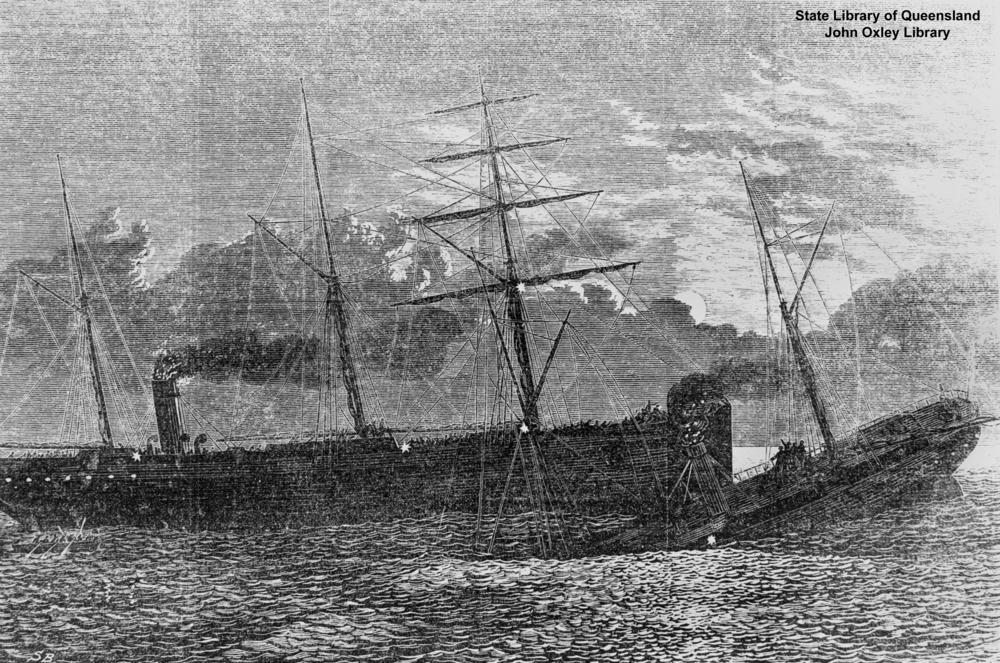

On a night where conditions are recorded as perfect and the moon shining brightly, the Bonnie Dundee was about 15 miles south of Newcastle on its way up from Sydney, when it collided with the much larger steamer, Barrabool who was on its way south to Melbourne. Recollections of the night are harrowing, as shipwreck survivors’ accounts always are. They tell of the panic and confusion that reigned, especially in the darkness, and that the Bonnie Dundee sank within five minutes of the collision.

The sinking of the Bonnie Dundee after the collision with the Barrabool. Courtesy State Library of Queensland.

The disaster did not play out like an accident and within 24 hours national newspapers were calling for an inquiry into who was to blame, particularly as the conditions were so favourable.

Suspicion and condemnation fell early upon the role of the Bonnie Dundee’s captain, John Alexander Stewart. An inquest was held into the death of Sarah Brown, the only passenger whose body was originally recovered. The inquest concluded with the jury finding a verdict of manslaughter as a result of ‘gross negligence’ against Captain Stewart and his chief officer Thomas Crawford. The Bonnie Dundee was found to have breached the Navigation Act by not holding its course and for crossing the Barrabool’s course twice. The collision had been completely avoidable.

The Barrabool in dock after the collision. Courtesy of the University of Newcastle archives.

No real explanation can be found for the Captain Stewart’s actions on the night and testimonies were conflicting.

An article from the Evening News appearing immediately after the collision in defence of the crew’s actions.

Public scrutiny also focused on why the female passengers were left behind on the rapidly sinking Bonnie Dundee. Sarah Brown and her daughter Margret, Ellen Dugdale, the ship’s stewardess Mrs White and a baby were all abandoned when the crew and male passengers quickly escaped into the only undamaged life boat or leaped onto the Barrabool just after the moment of impact. The teenage cabin boy George Pardell, recently arrived from England, tried to jump aboard the Barrabool but did not make it. His body was ultimately lost at sea.

The papers at the time was damning in their review of the night and called into question the crew’s behaviour. Reports noted that there had been enough men on board to render assistance and they should now ‘bear the brand of shame’ for letting the female passengers perish.

Captain Stewart, who redeemed himself very marginally by staying aboard his sinking ship like a true ‘British seaman’, said of the night:

I cut the two life-buoys adrift and gave them to the passengers. The stewardess (Mrs White) was holding an infant in her arms, and she threw it to the mate, who caught it in his arms. The female passengers were shrieking and terrified at the aspect of affairs. I requested them to cling to the life-buoys, thinking that they would bring them to the surface. The stewardess was comparatively cool and collected. We all five of us sunk beneath the surface together. I was taken down a good way before I got clear of the suction of the sinking ship and was also foul of some rigging, and with difficulty cleared myself. When coming to the surface. I saw no one. The two life-buoys were floating at a little distance. I succeeded in reaching one, and swam to the Barrabool, and was taken on board, and treated with every kindness by Captain Clark, and brought to Sydney.

– Captain Stewart, 11 March, 1879

Despite public interest and a guilty verdict for manslaughter handed to Captain Stewart and Thomas Crawford, little consequence came from the tragedy.

The Bonnie Dundee at its resting place, 4 kilometres east of Caves Beach. Courtesy of Michael McFadyen

Stewart and Crawford were never charged and were ultimately acquitted. The body of Ellen Dugdale was discovered five days later quite far from the wreck site, but those of her daughter Margaret and Mrs White were never found. George Pardell’s body was later uncovered inside a large shark caught by a shark fisherman working in Barrenjoey and was identified by Captain Stewart.

Much of the debate over the Bonnie Dundee tragedy focused on public concern about travelling by ship. Whilst ongoing fears would always exist for travel in severe weather and treacherous conditions, a calm night on a short, well sailed route should not pose a threat. Passengers had a right to feel as “safe as in their own dining rooms”. And yet here was a tragic combination of a captain’s incompetence compounded by a crew’s abandonment at the time when the passengers needed them most. Over time, interest in the Bonnie Dundee tragedy waned and certainly other wrecks and events took its place.

The Nicoll brothers, owners of the Bonnie Dundee, continued with their business and went on to have a substantial impact on the northern rivers region. The Canterbury Municipal Yearly Annual of 1885 says when speaking of the Nicoll brothers:

Some nine years ago Mr [Bruce] Nicoll of Sydney in conjunction with his brother opened up the Richmond River trade by laying on a line of steamers. At that time there were not more than 2,000 inhabitants in that rich and productive district. Since then, owing to the energy and enterprise of Mr Nicoll there are about 155000 people settled there…Nine years ago the Richmond River was practically unknown, to-day it is one of the most prosperous districts in the colony; and this is certainly owing to Mr Nicoll’s steamers opening up the district.

– Myffanwy Bryant, Curatorial Assistant