1930 poster – the landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay 1770 Australia. ANMM Collection.

Last week was the 245th anniversary of the arrival of Captain James Cook and HMB Endeavour at Botany Bay, just south of Sydney. Cook and his crew spent 8 days here from 29 April 1770, their first landfall on the Australian coast.

The moment of Cook’s landing took on a great consequence for Australians ever since. For non-Indigenous Australians, from the 1820s Cook was seen as a far better set of origins than Captain Phillip and his boatloads of convicts in the First Fleet. Indeed it was Cook’s landing at Kurnell on the southern headland of Botany Bay that was the preferred moment of commemoration right through the 19th and well into the 20th century.

Prior to 1901, the figure of Captain James Cook was a significant symbolic representation in the formation of an Australian ‘proto-nationalism’ — the mobilisation of British patriotism for an Australian colonial context. The first memorialisation of Cook at Kurnell occurred in 1822. Members of the Philosophical Society, an elite group of Sydney antiquarians led by Sydney ‘luminary’ and poet Baron Field, went on a day trip to locate the landing site. According to the society, the location was ‘verified’ by an Aboriginal person who remembered watching the landing. The memorialists promptly placed a plaque on a nearby rock. Field described it as ‘the only antiquity in the whole colony’, that piece of ‘classic ground where Cook trod’. A rock certainly fitted the Philosophical Society’s notion of a classic moment — something like the famous Pilgrims landing site at Plymouth Rock in America.

Image of Captain Cook’s landing site in 1855. Lithograph by John Degotardi after an artwork by F.C. Terry. ANMM Collection.

However in 1864, as the centenary of 1770 approached, the Australian Patriotic Association — who despite the name were particularly concerned with reminding Australians of their British origins — conducted an excursion to Kurnell to confirm Cook’s landing site. Armed with copies of Cook and Banks’ journals, they pronounced that the ‘actual site’ of Cook’s landing was in fact one kilometre away from the site established in 1822.

A leading figure in the Association was Thomas Holt, local member of parliament, businessman, physical fitness and cold bath devotee, and luminary of the Acclimatisation Society — devoted to making the Australian landscape British through the introduction of European flora and fauna. Holt was so enamoured with Cook he bought the land around Cook’s landing site at Kurnell and in 1871 marked it at great personal expense with a ‘needle’ monument in the classical style.

Holt continued to promote these annual ‘excursions’ until they were eventually enshrined as official commemorative practice by the end of the 19th century, when the government resumed the area for a public reserve.

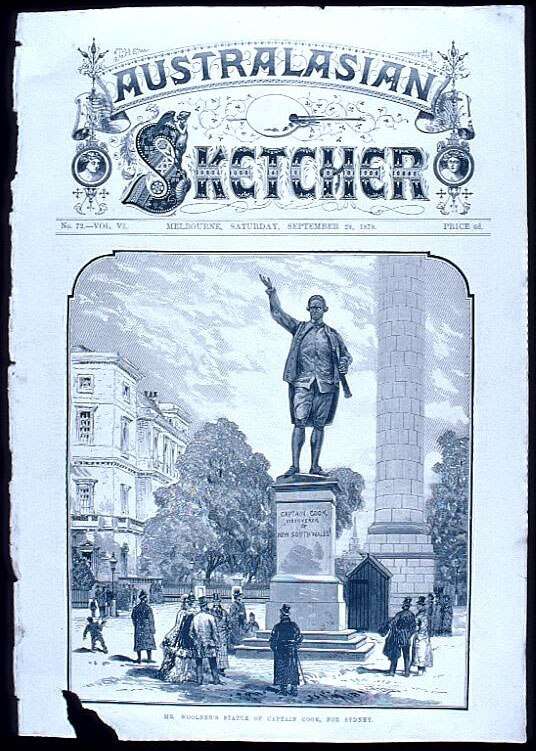

Cook’s connections to Australia were of great interest to late 19th century Australians trying to replace the convict origins of settlement with a better, more heroic and British one. Public interest in a statue of Cook in the centre of Sydney’s Hyde Park was so high that when it arrived in Sydney from Britain in 1879, according to one news report people congregated at Circular Quay ‘anxious to get the first glimpses’ of the statue in its crate … clambering up the framework … but only able to catch a sight of the legs or arms.’

Front page of the The Australasian Sketcher, Saturday 28 September 1878 featuring the Cook monument in Hyde Park, Sydney. ANMM Collection.

Although the 1888 centennial of course commemorated the arrival of the First Fleet, Cook was widely seen at the time as the real ‘founder of Australia’. At the Melbourne Centennial Exhibition amongst the various incarnations of Cook such as a ‘colossal bust’ of the ‘illustrious navigator’, was a ‘tableaux representing the scene of the landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay.’ Meanwhile in Sydney, Cook took precedence over Philip in the stained glass windows of the Town Hall building as part of a line up of Centennial heroes. During the centennial celebration parade, the largest of the ‘triumphal arches’ in George Street was topped by a model of the Endeavour and a large ‘medallion’ of Cook. Even at his own party, Governor Phillip found it hard to get a look in.

By 1901 it was widely believed that Anniversary Day (January 26, the date of Governor Phillip’s proclamation at Sydney Cove, now called Australia Day) commemorated Cook’s, not Phillip’s, arrival. As Cook’s was the likeness depicted in souvenir newspaper supplements, on ceremonial arches, illuminated transparencies and celebration ephemera, the public understandably continued to confuse the two.

Wedgwood figurine of Cook. ANMM Collection.

At Federation in 1901, a ‘dramatic reenactment of the landing of Captain Cook R.N. at Botany Bay’ was conceived as part of the Sydney celebrations. A week after the main ceremony in Centennial Park in Sydney, on the 7th of January 1901, a ‘Grand Pageant’ in the form of an historical reenactment took place at Kurnell in front of a large crowd.

After the reenactment of the landing, where ‘Cook’ and his party of ‘Marines’ and ‘Sailors’ fired a volley of muskets that ‘dispersed the natives’, Cook and ‘Joseph Banks’ walked up to a dias and along with the symbolic figure the ‘Nymph Australia’ delivered soliloquies of Australia’s destiny for greatness as the ‘Britannia of the Southern Ocean.’ Cook described the ‘wondrous’ land they had found and Banks concurred with his vision that ‘countless populations here may dwell, and in the distant days their cities build!’. Then the ‘beautiful maiden Australia’ appeared and proceeded to tell the actors Cook and Banks that their ‘hopes of future greatness’ had been realised.

Opposing Cook’s landing – published in Picturesque Atlas of Australasia, 1886. ANMM Collection.

In 1901, Aboriginal people still lived near the site of the reenactment, just across Botany Bay at La Perouse. Some had moved there from Kurnell itself — descendants of the people who witnessed and tried to defend the landing in 1770. Yet pageant directors recruited their supposedly more ‘authentic’ Aboriginal participants from northern Queensland.

When the pageantry and official proceedings had finished, the crowd gathered around the Queenslanders performing their ‘dances or corroborees’ and spear and boomerang throwing. This was reported by several journalists to have been the highlight of the day for the crowd. Apparently the Queenslanders received ‘more applause than Captain Cook.’

Cook’s landing was diligently commemorated in official ceremonies every year from 1899 right through to the 1950s. The practice of commemoration changed little over time — officiating dignitaries would head to Kurnell by steam ship, halt for a moment over the spot the Endeavour anchored, land, raise the flag, make toasts and speeches and depart back to the ship.

Another grand reenactment was held in 1951 for the jubilee of Federation. Even in the 1950s it was important for many to highlight Cook’s role in the ‘birth of modern Australia’. During the 1950s every anniversary day was duly kept by a small band of devotees, but by the 1960s the campsite and picnic grounds at Kurnell became more accessible by car for a growing numbers of ‘history tourists.’

By 1967 the site — an outpost of remnant bushland near a major oil refinery that was built in 1955 — had been taken over by the National Parks and Wildlife Service. Parks and Wildlife had to decide whether Kurnell was to become a sort of ‘reenactment’ of pre-1770 vegetation, or whether it should keep its rustic pine tree plantings and monuments to Cook’s landing. A compromise was developed that meant further monumentalising would cease, with the site kept as parkland for picnickers, but surrounded by native bushland. This was all done within the context of the impending anniversary moment — the Bicentennary of Cook’s Landing in 1970.

Lid to a board game of Captain Cook’s ‘voyage of discovery’ from 1970. ANMM Collection

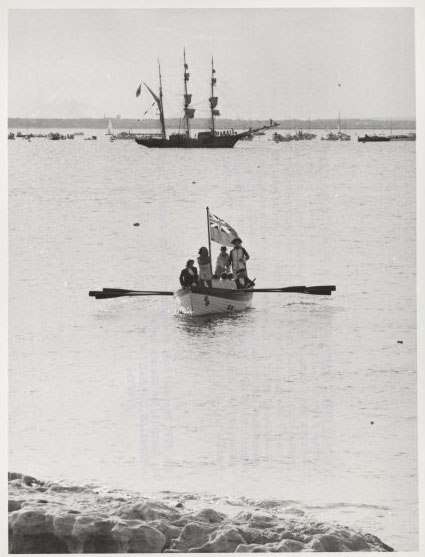

In 1970, then New South Wales Premier Robert Askin boasted that Australia was to stage ‘one of the greatest pageants ever held in the southern hemisphere.’ The organising committee claimed the reenactment of the landing of Captain Cook would be ‘portrayed in graphic detail.’ With the added attraction of the presence of Queen Elizabeth II, on 29 April 1970 the tall ship Monte Christo – re-registered for the ocassion as New Endeavour – ‘with 53 professional actors and naval ratings on board’, sailed into Botany Bay. Several ‘warriors’ waited ashore, including Aboriginal actors David Gulpilil and Ken Colbung, performing ‘domestic scenes’ of fishing. A stingray was treated with shark repellant and guarded by two skin divers so it was available at the right moment to be speared by the Aboriginal actors. Fibreglass canoes were camouflaged by bark and leaves into ‘bark canoes’.

Bill Brindle, Reenactment of the landing of Captain Cook at Kurnell, in Botany Bay, 1970, nla.pic-vn3585892. Courtesy National Library of Australia.

The serious history of the reenactment was disrupted by university students, one of whom was dressed in a Captain Cook hire-costume. They arrived at the landing site in a speedboat and took possession of Australia ‘in the name of George the Third and Sydney University.’ The fake ‘Cook’ tried to claim centre stage and doff his hat to the Queen before being arrested. The bogus Cook, at first believed by some to be the ‘real’ Cook, ‘drew loud cheers from the crowd.’

The reenactment was the climax of nationwide Cook celebrations that coincided with a vigorous promotion of Australian history to a receptive public, increasingly fascinated with Australian and family history. Federal and State funding was offered for Cook-related projects such as monuments, festivals, parades and reenactments. Inland towns and places not along Cook’s historical route could obtain funding for any project that was related to history. Many coastal towns performed their own versions of Cook’s landing.

The centre-piece of national celebrations proved to be more popular than organisers anticipated. The expected crowd of 15 000 turned into fifty thousand. People camped overnight nearby and when traffic on the road to Kurnell came to a standstill, people walked the eight kilometres to be on time for proceedings.

By 1970 the message of the reenactment of Cook’s landing had shifted from one of British destiny to to a focus on exploring the ‘encounter moment’ — the strangeness and curiosity from both sides of the beach sustained the drama of the reenactment. It was also important to the organisers to point out that a descendant of the ‘Turawal’ (Dharawal) people took part in proceedings.

We might recall the significant Indigenous protests of the 1988 Bicentenary. But in 1970 there were also important protests against the celebration of Cook’s landing moment by Indigenous Australians.

While Queen Elizabeth watched the reenactment, Aboriginal protesters across the bay at La Perouse threw funeral wreaths into the water, aiming them to drift into Her Majesty’s view. The irony of an Aboriginal presence only hundreds of metres away that mourned death, whilst the Cook reenactment claimed to celebrate the ‘birth’ of modern Australia was not lost on many. In Melbourne during the 1970 celebrations protesters descended on Cooks’ cottage that had been transported to Australia brick by brick in the 1930s. They surrounded the cottage and called for the return of land to Aboriginal people.

The commemorative landscape of Australian history has changed in recent years. In 2000 the National Parks and Wildlife Service renamed the Kurnell parkland ‘Botany Bay-Kamay National Park’, according to one news report to show that ‘when Cook turned up there were already people here.’ In 2003 the name ‘Captain Cook’s Landing Place’ was changed to the ‘Meeting Place Precinct’. Aboriginal people have since participated in the commemoration — titled ‘The Meeting of Two Cultures’ — as a reconciliation event, though many still hold strong views on the symbolic importance of Cook’s landing moment as the beginning of the British invasion of Australia.

The 19th and 20th century manufacturing of a ‘public’ history for Cook — generally by government officials, businessmen and politicians — significantly influenced subsequent commemorative undertakings and representative forms. Colonial elites in nineteenth-century Australia were concerned with establishing Captain Cook as the beginning of Australian history and enforcing indigenous history as ‘pre-history’.

It is important to understand how such commemorative moments have transformed and been shaped over time. April 29 was asserted as a ‘foundation moment’, contested by Aboriginal people, and eventually faded from prominence — a mere shadow of the grand reenactments of 1901, 1951 and 1970. With the 250th anniversary of the Endeavour‘s passage along the east coast fast approaching, what will the commemorative landscape around Captain Cook look like in 2020?

— Dr Stephen Gapps, Curator

___

This post is based on a chapter of my PhD thesis, ‘Performing the Past: A history of historical reenactments‘ (2004, University of Technology, Sydney) which investigated the cultural history of parades, pageants and historical reenactments and explored the heightened representational dilemmas and contested nature of Cook in public performances.

Newspapers

SMH 23/5/1871 p2, SMH 27/1/1888 p8, Argus 27/1/1888 p6, SMH 29/4/1899 p3, SMH8/1/1901, SMH 8/1/1901, SMH 8/1/1901, SMH8/1/1901, Daily Telegraph 6/5/1901, The Age Exhibition Supplement 28th August 1888 p3, The Australian 30th April 1970 p1,3, SMH 30th April 1970 p6, Daily Telegraph 30th April 1970 p2, SMH 4th March 2000 p1.

Archival

Reports and Minutes of the Captain Cook Bi-Centenary Celebrations Organising Committee AONSW, Official Programme of the Reenactment of Captain Cooks Landing with list of cast. James Cook Ephemera ML, Summary of activities and events of the Captain Cook Bicentenary Celebrations 1970. James Cook Ephemera ML, Captain Cook’s Landing Place Trust Minutes 1954-67 ML, Endeavour Players Captain Cook 1959 NFSA, Captain Cook Landing Place Trustees 150th Anniversary of the Entry of Governor Phillip into Botany Bay, D H Paisley Government Printer 1938.