Whilst looking though the artefacts from the Dunbar shipwreck, it is difficult to imagine that anything amongst the dull metal was ever intended to decorate people’s homes. Ship fixtures blend with metal domestic and commercial goods and all have acquired the dull lacklustre look acquired by years under the sea.

Artefact from the Dunbar wreck.

ANMM Collection.

Yet amongst the piles of screws, nails and concretion are some lovely examples of metal work in the shape of flowers and leaves. These pieces had obviously been part of some elaborate Victorian pieces of furniture intended to adorn the houses of Sydney. Even more lovely was when I was able to find not only the maker of some of these pieces but also what they would have originally looked like. Not so dull after all it seems!

The Victorian era, of which Dunbar was right in the thick of, was renowned for its love for ornamentation of the home. Despite strict personal morals and codes of conduct, interior design of the time embraced the motto of “more is more”. There was no surface too cluttered, no pattern too bold or metal too shiny. Fueled by the Industrial Revolution, makers could constantly churn out new and more ornate designs to feed the style-hungry and growing middle class.

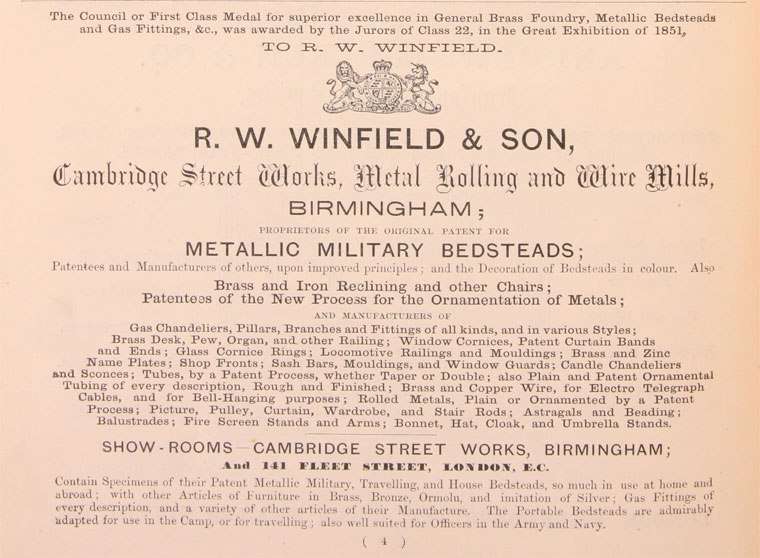

An advertisement for R.W.Winfield showing their extensive range and 1851 Council Award.

One such firm was R.W.Winfield. They were a brass foundry based in Birmingham which at the time was the centre of the industry. Of course the company also had a fashionable showroom in London and advertised themselves as makers of brass picture hooks, military bedsteads and everything in-between. R.W.Winfield became very well known for their range of domestic brass beds and brass tube furniture.

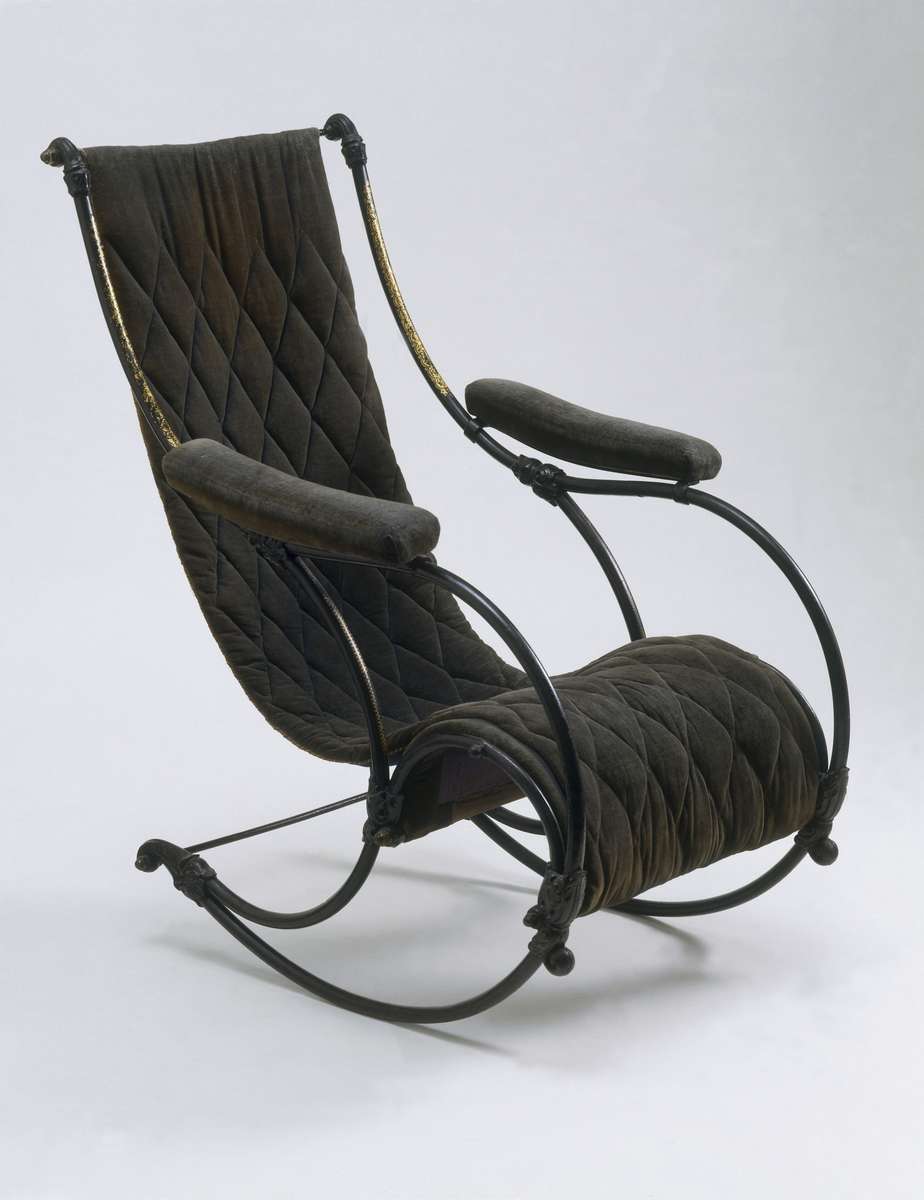

It is no surprise then to see the firm appearing at The Great Exhibition in London in 1851. The exhibition had over 13,000 exhibits and over one million items on display. Over the six months it was open it was visited by over six million people and was a resounding success on many levels. R.W.Winfield came away with a very coveted Council Award. Only 174 of these awards were bestowed and were awarded in recognition of great ingenuity and innovation. The award itself was for the firm’s brass dismantling armchair. The judging panel, which included the exhibitions primary organiser Sir Henry Cole, were incredibly impressed with its simple design and easy assembly and disassembly. To this day the armchair is still highly regarded for its simplicity of line and ingenuity.

A R.W.Winfields rocking chair. Similiar in style to their award winningexhibit of 1851.

Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

However, the winning chair design was only a part of the R.W.Winfield’s market and a small part at that. The public demanded more ornate and highly embellished goods and that was where the money was. The firm continued to be prolific in its brass tube furniture and decorator items such as lamps and curtain rods. It is these items that seem to have been on board Dunbar. Although at the time the city of Sydney could boast over 100 furniture makers and around 18 brass founders, it is likely that pieces from London were being imported for sale or certainly being bought over by passengers recently visiting London. After their success at the Great Exhibition, R.W.Winfield would have been a label people would have been happy to have in their home. It is said even Queen Victoria purchased one of their wall lamps after visiting their exhibit.

Remains found from the wreck of the Dunbar.

ANMM Collection.

The R.W.Winfield curtain rod holder used by Sir Cole as an example of unacceptable interior decorating.

Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

There is no doubt that the decorative remains found on the Dunbar wreck were the latest in Victorian era parlour room style. The pieces seem gaudy to our modern tastes now, especially as they would have been set amongst heavy brocades, dark wood, tassels and trims. The decorating style still reflected a strict adherence to the English notion of taste rather than the conditions found in Sydney. Imagine spending an Australian summer surrounded by all that!

And yet by contemporary accounts life in Victorian Sydney for the wealthy was not too bad:

“The best time to see this neighbourhood in all its glory is on a summer’s evening, about an hour after sunset, when the drawing rooms are in a blaze of light. Then the rich tones of the piano or some other musical instrument are heard gushing forth from the open windows, accompanied by the sweet melody of female voices … Beautiful ladies, dressed in white may be seen sitting upon the verandahs, or lounging on magnificent couches, partially concealed by the folds of rich crimson curtains in drawing rooms which display all the luxurious comforts and magnificence of the East, intermingled with the elegant utilities of the West.” (Dictionary of Sydney)

As an interesting note to the future of R.W. Winfield, the firm achieved publicity again just a year after its award winning appearance at The Great Exhibition. Sir Henry Cole, that grand purveyor of good taste and soldier against vulgarity, mounted an exhibition in London titled “Examples of False Principles of Decoration”. Cole had an intense dislike for the ostentation of Victorian design and was well known for his efforts to educate the British public on good decorating taste. One of the 78 unfortunate pieces to be displayed in Cole’s exhibition was the lily curtain rod holder by R.W. Winfield, similar to the one found on the Dunbar wreck. The rod holder was deemed unfit for use as it was ‘a direct imitation of nature’ and therefore ‘possessing unfitness of purpose’.

It seems none of this criticism mattered for the passenger aboard the Dunbar who obviously thought the much-maligned rod holder still lovely enough to find a new home in Sydney.

Myffanwy Bryant

A R.W.Winfield lamp. So popular even royalty had one.

Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.