Jeanne Baret was a talented and ambitious young woman who escaped a life of rural poverty in the mid-18th century and, disguised as a man, set out on a risky journey of botanical discovery. In doing so she became the first woman known to circumnavigate the globe.

The first known image of Jeanne Baret, from 1816. From Navigazioni di Cook del grande oceano e intorno al globo, Volume 2, 1816, Sonzogono e Comp, Milano. Reproduced courtesy State Library of NSW, FL3740703

In September 2019, 77-year-old British woman Jeanne Socrates became the oldest person to circumnavigate the world alone, non-stop and unassisted. It was an enormous achievement in the history of sailing. She attributed her success to the fact that she had ‘persevered and overcome so many problems on the way around’.1 Another Jeanne, 250 years earlier, might well have laughed wryly at this understatement. In her own way she had also circumnavigated the world and overcome various trials, although in her case it had taken nine long years to get home.

In 1767, Europe was in the midst of the Enlightenment. European powers had a mania for exploration and were scrambling for new territories and trading partners. With scientific aspirations and wide political support, King Louis XV of France agreed to an expensive round-the-world expedition headed by Louis de Bougainville. This ambitious journey – the first of its kind for France – was as much a display of power and influence as a practical expedition of discovery. The ships assigned for the trip were the frigate Boudeuse and the slower supply ship Etoile. The Etoile carried a mixed bag of officers and crew under the leadership of the experienced and level-headed Captain François de la Giraudais.

Philibert Commerson was awarded the role of expedition botanist directly by the king, and was directed to ‘make all the observations and relative discoveries on the coasts and even in the interior of the various countries’.2 Such an ambitious undertaking allowed Commerson his own cabin to house the extensive equipment and resources that would be required. He was also permitted to bring a personal assistant. Commerson was known for being particularly zealous in his collecting, often at a high physical cost to himself. His intensity was also reflected in a difficult personality. He was described as ‘waspish’, with little tolerance for those who did not support his endeavours. Ambitious, judgmental and single-minded, he was not the ideal candidate for a two-year journey at sea.

It would be difficult to imagine a more hostile environment than below the decks of an 18th-century naval ship, where hardened men lived by their own rules to survive in cramped and confronting conditions for years on end. So at Rochefort in western France in February 1767, when Commerson and his servant boarded the Etoile, their trepidation must have been considerable. Neither had been on a ship before and neither could have anticipated the conditions they were walking into. This was perhaps more so for Commerson’s cabin boy, ‘Jean’, who was actually a woman named Jeanne Baret.

Jeanne had been born in rural Poil, in central France. Although poor, she was clearly intelligent and determined enough to make her way out of her tiny village to the nearby town of Toulon-aux-Arroux, a world away from where a woman in her circumstances could have expected to end up at that time. Here she became housekeeper for Commerson and began to assist him in his botanical work. Over time, with Commerson’s physical ailments restricting him more and more, Jeanne seems to have become indispensable. When Commerson moved to Paris to further his career, Jeanne accompanied him.

Much has been made of Jeanne’s devotion to Commerson and she is often referred to primarily as his lover. But while she was in a relationship with Commerson, theirs was not an adolescent romance – they were 27 and 40 respectively – nor did Commerson’s personality suit the ideal of a romantic hero. This narrow view also reduces Jeanne’s role in Commerson’s life to an accessory and certainly undermines her own individual achievements. For it is clear that both were ambitious, and over time their partnership grew into one of dependency and collaboration. They never married, although they had a son together whom they adopted out, and their story was much more complex than that of a master and a housekeeper restrained by class conventions.

Philibert Commerson by P Pagnier, 19th century. Image © Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris

We can only speculate on what happened when Commerson was awarded his coveted role on Bougainville’s expedition, and it is easy in hindsight to attribute reasons for the risks the pair took. Did Jeanne ask to accompany Commerson out of loyalty, or because of her own intellectual pursuits or a desire for new experiences? Or did Commerson ask Jeanne to come, realising that he was unlikely to achieve his scientific goals without her assistance? While a male apprentice might have provided professional support, Commerson’s persistent ill health now required a personal carer also, and to reveal this might have jeopardised his prized royal appointment. In Jeanne, he had the best of both roles. Their decision probably combined all of these reasons, both knowing this opportunity was too important to turn down.

Jeanne was certainly not the first male impersonator in the 18th century. Some, such as soldier Hannah Snell or pirate Mary Read, both British, were celebrated through ballads, books and stage shows. There were probably other women whose true identity was never revealed. Of those who were exposed and told their stories, there were accepted reasons – mainly romantic or patriotic – that explained their unconventional actions. Mostly, they were thought to have assumed a disguise to follow a lover – with the assumption that they would later live happily ever after – or to fight for their country. Whatever narrative was spun, these wayward women would always return safely home and resume a traditional female life. Part of the appeal of such stories for the public was how the women managed to keep their disguise amid groups of men. For Jeanne, heading into open oceans for years, it was of particular concern.

From the outset, life on the crowded 104-foot (32-metre) Etoile was difficult. Commerson was sick for weeks and a persistent leg ulcer confined him largely to the cabin. Although this might have supplied a plausible reason for ‘Jean’ to be constantly by his side, including sleeping in his cabin, suspicion grew quickly on board at the devotion the cabin boy showed his master. When the Etoile reached Rio de Janeiro in June, the suspicions about Jeanne appear to have become more solid, with one source suggesting that de la Giraudais was informed of the deceit happening under his nose.3 When the expedition left in November, however, Jeanne and Commerson remained aboard, accompanied by a bulging collection of specimens foraged ashore.

Bad weather dogged the onward journey and unresolved tensions continued to fester. Commerson equated shipboard life to living like a mouse in a trap, where ‘nothing can be done and one can only gnaw at the bars’.4 When the exhausted expedition reached Tahiti in April 1768, the ruse was finally exposed – not by the Etoile crew, but by the Tahitians. Bougainville records that they took one look at Jeanne and knew she was a woman. His journal entry on the event is brief but very telling, and records the lies Jeanne told in an attempt to mitigate the deception:5

For some time there was a report in both ships, that the servant of M de Commerçon, named Baret, was a woman. His shape, voice, beardless chin, and scrupulous attention of not changing his linen or making the natural discharges in the presence of anyone, besides several other signs, had given rise to, and kept up this suspicion. But how was it possible to discover the woman in the indefatigable Baret, who was already an expert botanist, had followed his master in all his botanical walks, amidst the snows and frozen mountains of the Strait of Magellan, and had even on such troublesome excursions carried provisions, arms, and herbals, with so much courage and strength, that the naturalist had called him his beast of burden?

A scene which passed at Tahiti changed this suspicion in to certainty. M de Commerçon went on shore to botanise there; Baret had hardly set his feet on shore with the herbal under his arm, when the men of Tahiti surrounded him, cried out, It is a woman, and wanted to give her the honours customary on the isle. The Chevalier de Bournand, who was upon guard on shore, was obliged to come to her assistance, and escort her to the boat. After that period it was difficult to prevent the sailors from alarming her modesty. When I came on board the Etoile, Baret, with her face bathed in tears, owned to me that she was a woman; she said that she had deceived her master in Rochefort, by offering to serve him in men’s clothes at the very moment he was embarking; that she had already before served a Geneva gentleman at Paris, in quality of a valet; that being born in Burgundy, and become an orphan, the loss of a law-suit had brought her to a distressed situation, and inspired her with the resolution to disguise her sex; that she well knew when she embarked that we were going round the world, and that such a voyage had raised her curiosity.

She will be the first woman that ever made it, and I must do her the justice to affirm that she has always behaved on board with the most scrupulous modesty. She is neither ugly nor handsome, and is no more than twenty-six or twenty-seven years of age. It must be owned, that if the two ships had been wrecked on any desert isle in the ocean, Baret’s fate would have been a very singular one.

Despite Bougainville’s obvious admiration for Jeanne, and Commerson’s insistence that he had also been deceived by her disguise, the captain knew the situation must be resolved, both for Jeanne’s safety and French naval regulations at the time. While Bougainville clearly could not abandon Jeanne in Tahiti, neither could he return to France with her still on board after years at sea. And so Jeanne remained on Etoile, sequestered from the disgruntled men, enduring the ordeal as the months wore on. And wear on they did. The expedition became fraught with difficulties and was now a voyage of endurance rather than discovery. Food and water shortages exacerbated the sickness that ravaged the ship. After resorting to eating the ship’s rats, Bougainville at last ordered the ship’s dog to be served up to his starving officers. Adverse weather reduced the voyage to a sluggish crawl until at last the two ships limped into the colonies of the Dutch East Indies, and deliverance.

Portrait of Louis de Bougainville by Louis Boilly. Bougainville was a highly acclaimed naval and military commander who also showed sensitivity and respect for Jeanne, and ensured she was not forgotten later in life. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-296177599

While the most pressing concerns of the expedition had now been resolved, others lingered. It is likely that Bougainville realised that the scientific and exploration potential of the voyage was exhausted, as disappointing as that must have been. He set a course for the French settlement at Mauritius and home. And of course, there was still Jeanne. Bougainville had not forced her ashore in Batavia (present-day Jakarta, Indonesia) and perhaps he had always intended to leave her in Mauritius. He does not mention her again in his journal, but certainly when the expedition left Mauritius five weeks later, Commerson and Jeanne were left behind in Port Louis with the French governor, Pierre Poivre.

This arrangement did not raise as many questions as it could have, as Poivre himself was an avid botanist and had established an impressive botanical garden outside of Port Louis, which remains to this day. He enthusiastically engaged Commerson to study the surrounds, including Madagascar, and of course Commerson’s loyal servant remained with him. And so, after 22 months of hellish shipboard life, Jeanne found herself back on land and in relative safety. There is no record to indicate whether she shed her male disguise, but we do know she remained with Commerson on Mauritius until he died in March 1773. During their shared time there, the couple dedicated themselves to studying the flora of the region, collecting and recording more than 1,000 species, despite Commerson’s persistent ill health and dwindling finances.

With the death of Commerson, Jeanne was left to fend for herself. As had been the case on Etoile, Commerson had made few friends on the island, and dispatches back to Paris referred to him as being an ‘ill-natured man, capable of the blackest ingratitude’.6 Without money, status or social support, Jeanne survived; court records show she opened a tavern in Port Louis and in 1774 was married to Pierre Duberna(t).

On her eventual return to France with her husband the following year, no publications appeared revealing salacious details. There were no theatre tours, ballads or public appearances. Nor were there any botanical publications authored by her or any discoveries attributed to her. Jeanne, true to the quiet fortitude she had always displayed, claimed some money that Commerson had left her in his will and settled into a rural life. But she had not yet been completely forgotten. Ten years after her return to France, Jeanne Baret was paid by the French navy. Despite having broken French naval code by joining the journey in disguise, Jeanne received a pension for her courage and exemplary behaviour on the voyage. It would seem that Bougainville, still an admirer of the very qualities he had observed a decade earlier, was now officially able to recognise Jeanne’s extraordinary achievement.

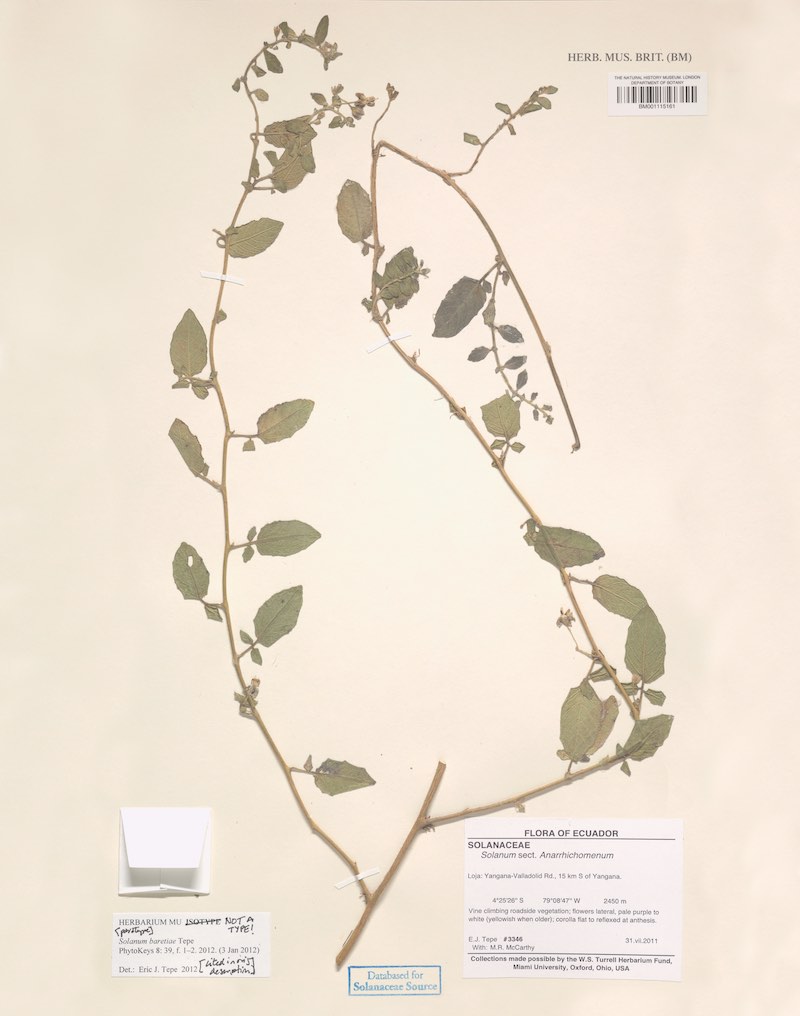

Solanum baretiae Tepe. Image courtesy Natural History Museum, London. Collection number BM001115161

And so Jeanne passes quietly into history, largely unheralded and voiceless in a story where the voice most needed is hers. The novelty of Jeanne’s disguise, and the drama of her exposure and subsequent tribulations, should not overshadow the significance of her uncredited scientific achievements. Although the objectives of the Enlightenment directed much of her life, they were not intended for women of her class, of whom very little was expected. Jeanne’s ability to successfully overcome the restrictions of her origins, to embrace the mental and physical challenges of early botany, to constantly care for Commerson while in restrictive disguise and personal danger, is nothing short of extraordinary. And by making it back to France, she became the first woman known to have achieved a circumnavigation, of which Bougainville was well aware.

It was most likely Jeanne Baret who, in 1767, collected the popular bougainvillea plant that adorns so many Australian gardens today – yet no plant was officially named for her until 2012, when Solanum baretiae, a species of nightshade, was finally given the honour.

Commerson, despite his many faults, did try to name a species for Jeanne. They collected the plant that Commerson wanted to call Baretia in 1771 at Bourbon (now Réunion), but a decade later its name was changed to Quivisia.

Solanum baretiae, a species of nightshade named by Eric Tepe in 2012 in recognition of Jeanne Baret. Image courtesy Eric Tepe from the University of British Columbia

Despite this, Commerson’s sentiments at the time still hold true:7

This plant is dedicated to the valiant young woman who, assuming the dress and temperament of a man, had the drive and audacity to travel throughout the world ... inspired by some divinity, she frustrated the schemes of men and beasts, risking on many occasions both her life and honour. We are indebted to her heroism for so many plants that have never before been collected, for so many herbaria carefully put together, so many collections of insects and shells, that it would be an injustice on my part, as it would be for any other naturalist, if I did not pay her the greatest tribute by dedicating this plant to her.

References

1 Aamna Mohdin, ‘British woman, 77, becomes oldest person to sail around the world alone’, The Guardian, 10 September 2019.

2 John Dunmore, Monsieur Baret, Heritage Press, Auckland (2002), p 35.

3 John Dunmore, The Pacific Journal of Louis-Antoine Bougainville 1767–1768, Hakluyt Society, London (2003), p 228.

4 Dunmore, Monsieur Baret, p 55.

5 Bougainville, Louis, A Voyage around the World ..., John Nourse, London (1772), p 300.

6 Dunmore, Monsieur Baret, p 179.

7 Jeannine Monnier et al, Philibert Commerson, Association Saint-Guinefort, Chatillon-sur-Chalaronne, 1993, p 98.