Weird, wonderful, quirky – and odd.

Humans seem to have an innate drive to collect the weird, odd and wonderful … and then display those objects for others to gape at or bask in. Before the modern museum, there was the European tradition of the Cabinet of Curiosities. Private collections, sometimes undertaken in the name of early modern science, but just as often collected for whimsy and wonder.

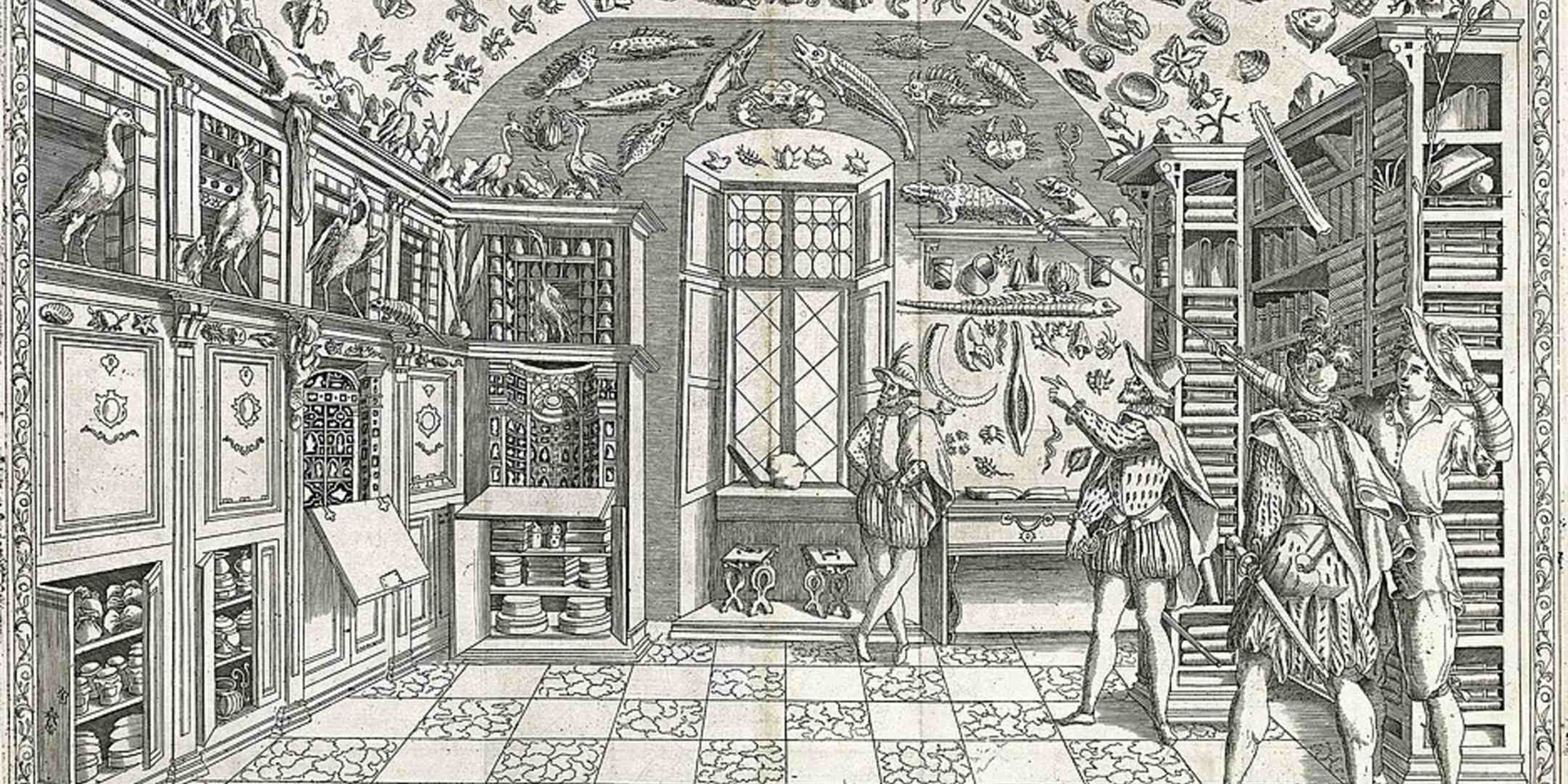

Illustration of an Early Modern European cabinet of curiosities. This one has a strong natural history theme. Source: Wikimedia

At the museum, we collect, preserve and document Australian’s relationship with the sea – and yes, even we have a few ‘unique’ objects in the collection which would not have been out of place in Cabinets of Curiosities in the past.

Not every item in our collection is a beautiful painting or a magnificent ship model, but the oddities have their own stories and significance to our relationship with the sea. Discover some of these curious items below.

The Lamp

.jpg?la=en)

This electric lamp is made from the dried penis of a whale. ANMM Collection 00042380

Oddity scale: Whaley hard to measure

What the object label says:

This electric lamp is made from the dried penis of a whale. Mounted on a wooden plinth with a standard light bulb, cord and plug, it is a highly unusual example of the way whale products have been souvenired and fetishised. While whale oil, meat and bone have traditionally been highly sought after, the whale's penis has little commercial use. The distinctive use of the penis is representative of the collecting habits of the whalers themselves, and those involved in the whaling industry.

What the object label does not include:

Here at the museum we have a large collection of scrimshaw (a collection which deserves its own blog) and this lamp, acquired in 2004, is certainly a conversation starter!

Recent genotyping and carbon dating by the Conservation team indicates that this tissue is from a sperm whale and was harvested post-1950. We previously thought it was made around 1930.

Fun fact: Every time this object is displayed there is always a debate between the Conservation and Curatorial teams as to how to light the lamp. Should we use a bulb strong enough to showcase its true glory? Will that damage the internal structure of the lamp due to the light exposure? The last time it was displayed in 2014, they agreed to have a push button on the side of the showcase for visitors to turn on the light only for the short duration of two minutes at a time.

Consider too that the light bulbs originally used in this lamp are no longer easily available or energy efficient. There’s some emerging chatter in conservation circles in favour of LED lights to be used in the display of older lamps. LED lights are more readily available, don’t run hot and we can measure both their lux and UV output more precisely, further reducing potential damage to objects.

Evolving display methods mean that this object could – in theory – be displayed more often. While this item is currently in storage, you can view a 3D model of it below.

The Trophy

John Walker Intercolonial Sailing Carnival trophy. ANMM Collection 00048268

Oddity scale: Terrifying (but it was once considered very bonnie)

What the object label says:

This trophy is a rare example of a sporting trophy in the form of a ram' s head with a silver ash tray, cigar stand and was awarded to the Australian champion 22-foot skiff from 1896. A very similar trophy, known as the Taymouth Ram is on display at the Kenmore Hotel adjacent to Taymouth Castle (now a golf club) in Perthshire Scotland. It was used as a table setting/snuff box and from 1926 it was the MacTaggart family perpetual trophy presented to the winner of the Men's open Golf tournament day at Taymouth Castle Golf Course.

What the object label does not include:

I’ve had the pleasure, several times over the years, of jumping at the sight of the little grin poking out unexpectedly in the dim shadows of the collection store. Yes, the eyes do follow you.

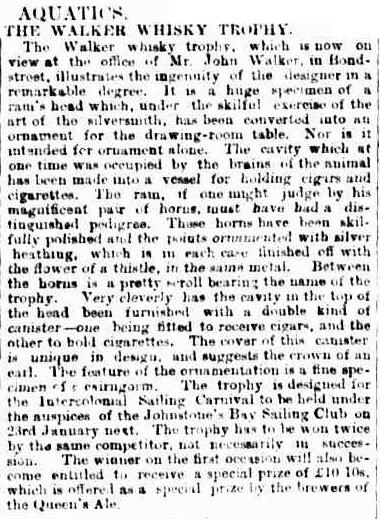

The trophy bares the maker’s mark of ‘R&HB Kirkwood, 66-68 Thistle Street Edinburgh’ and it was custom made for the John Walker Intercolonial sailing race, as reported favourably in the Sydney Morning Herald, 19 December 1896:

The Walker whisky trophy, which is now on view at the office of Mr. John Walker, in Bond Street, illustrates the ingenuity of the designer in a remarkable degree. It is a huge specimen of a ram’s head which, under the skillful exercise of the art of the silversmith, has been converted into an ornament for the drawing-room table. Nor is it intended for ornament alone. The cavity which at one time was occupied by the brains of the animal has been made into a vessel for holding cigars and cigarettes. The ram, if one might judge by his magnificent pair of horns, must have been a distinguished pedigree. These horns have been skillfully polished and the points ornamented with silver heathing, which is in each case finished off with the flower of a thistle, in the same metal. Between the horns is a pretty scroll bearing the name of the trophy. Very cleverly has the cavity in the top of the head been furnished with a double kind of canister…the cover of this cannister is unique in design and suggests the crown of an earl…The trophy is designed for the Intercolonial Sailing Carnival to be held under the auspices of the Johnstone’s Bay Sailing Club on 23rd January next. The trophy has to be won twice by the same competitor, not necessarily in succession….

A bonnie description of the trophy in Sydney Morning Herald, 19 December 1896. Source: Trove, National Library of Australia

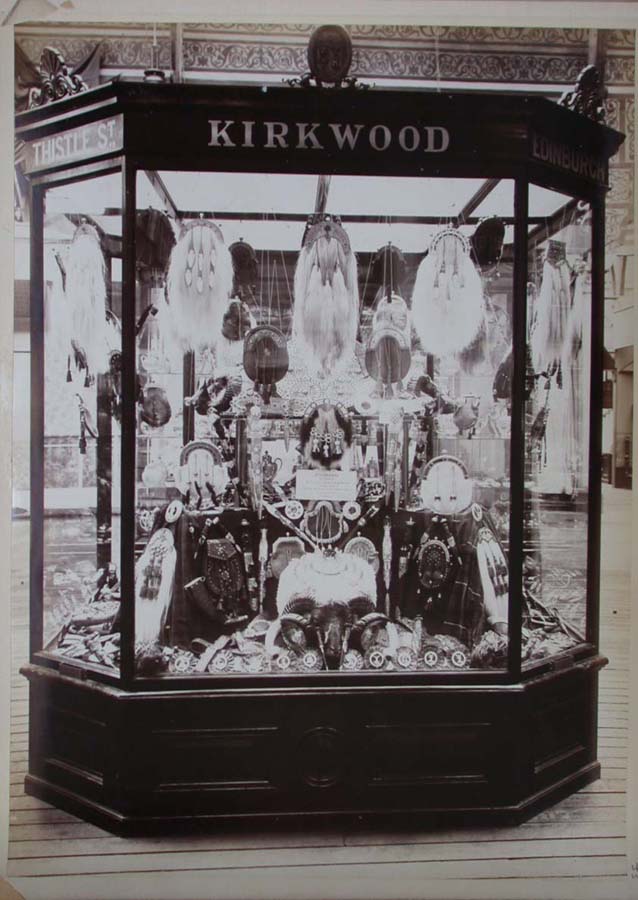

Kirkwood silversmiths were known for their military badges, brooches and accouterments. They were fancy enough to have a display at the Glasgow Exhibition of 1888, featuring a ram trophy (and lots of sporrans). The exhibition was held to draw attention to Scottish science, industry and art. There are similar trophies in collections around the world, including other UK collections and at least one in New Zealand.

A display of the silversmith artistry and traditional highland trophies from Kirkwood, at the 1888 Glasgow Exhibition including a ram's head (lower center front of the cabinet). Source: University of Glasgow.

The oddest part is that our ram’s head is an Australian Merino – not a native Scottish ram – so how did that come to be? Was this trophy commissioned? Why was a Scottish tradition given an Aussie twist?

While this item is also in storage, the video below includes great close-ups of this unique trophy.

The souvenir

.jpg?la=en)

Stuffed albatross head mounted in a miniature ship's lifebuoy of the ship Euryalus. ANMM Collection 00029929

Oddity scale: Quirky, if taxidermy is your preferred way to remember a holiday

What the object label says:

A souvenir from the Euryalus featuring a stuffed albatross head mounted in a miniature ship's lifebuoy. A merchant seaman probably made this souvenir of the steamer Euryalus around 1900, using an albatross head as novelty.

What the object label does not include:

Clearly some sailors don’t adhere to the warning of Coleridge’s Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner and instead choose to use parts of sea birds to create one-off mementos. Fitting, as the market for mass produced plastic life buoy souvenirs didn’t take off until after World War II. Before then not only was there less choice but, more often, souvenirs were handmade and customised. Hence this artful assemblage.

The albatross head was gifted/donated to the museum in 1997. We estimate it was made around 1900. Our records show the donor seems to have brought it off their neighbour at an estate sale, believing the neighbour’s late husband had crafted it.

What makes this stand out from other albatross art is the use of the whole head. Other examples of albatross art normally used the feet to make purses, curving bones into pipes as they were nice and hollow or using beaks as handles for walking sticks and umbrellas.

As you can see, it's due for a new photograph so the Conservation team are preparing to retest the object for arsenic, lead, mercury and other common chemicals of taxidermy past practice before we take it to the photography studio. It might make an interesting 3D model too…

Still curious for more oddities in museum collections? Then you need to check out the #CURATORBATTLE hashtag on twitter, which recently included a hilarious battle for the creepiest object.