The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 is turning many eyes back to 1919. Coinciding with the end of World War I, the risk of ‘Spanish flu' coming to Australia aboard troop transports was very real. Dr Peter Hobbins explores what troopship records reveal about life, death and discipline during the pneumonic influenza pandemic.

Frank Bell's war ended spectacularly. Just 10 days after the armistice of 11 November 1918, this Royal Australian Navy stoker bore witness to a dismally impressive sight. As he recounted in his diary, ‘we met & took under escort a portion of the German Fleet … consisting of 50 Destroyers, 8 Light Cruisers, 5 Battle Cruisers & 10 Battleships’. Frank’s own warship, the light cruiser HMAS Melbourne (I), was detailed to shadow a fellow light cruiser into captivity. As they swung into place beside SMS Nürnberg (II), Frank reflected that ‘It was a grand sight after 4½ years of war to watch the German ships go by in simple line ahead, & to realise that the war was really over’.1

Commissioned into the Royal Australian Navy in 1913, HMAS Melbourne (I) took part in the 1914 campaign to capture the German colony of Nauru and ended World War I on patrol in the North Sea. Frank Bell served as a stoker on Melbourne throughout the war. Gift from Kim Andrews, ANMM Collection 00017353

Yet for Frank and 165,000 other Australian servicemen, the end of World War I did not mean instant repatriation. Rather, they joined a further 15,000 women (nurses, wives and sweethearts) in awaiting their turn for passage home. While some elected to pay their own fare aboard a commercial steamer, most travelled by troopship. Hired by the Commonwealth Government, military transports busily ferried Australians home until the process was completed in late 1919. This peacetime flotilla quietly conducted the greatest mass movement of people to Australia since the gold rushes of the 1850s.

An infamous passenger

With a berth aboard a transport determined largely by the duration of military service, Frank was fortunate. Having enlisted in June 1913 – more than a year before hostilities commenced – the 28-year-old earned an early ticket home.2 Accompanying Frank on his passage were men and women from almost every Australian Imperial Force (AIF) service, corps and battalion, representing diverse civilian trades and professions. On 8 January 1919, Frank joined 80 fellow sailors, over 1,300 soldiers, 55 officers and 10 nurses embarking on Hired Military Australian Transport (HMAT) A67.

More commonly known by its peacetime name, RMS Orsova, this was an impressively modern liner of 12,036 tons. Clyde-built for the Orient Steam Navigation Company, the ship first sailed to Australia in 1909.3 Featuring electric lighting, ventilation and clocks, the steamer also boasted two electric plate-washers and an electric potato-peeler. Despite these labour-saving facilities, Orsova still required a crew of 336 hands, meaning that more than 1,800 people were pressed aboard as the transport sailed southward on that January afternoon a century ago.4

Through its career as HMAT A67, RMS Orsova ferried troops, nurses and wounded between Australia, the Middle East and Europe. After being torpedoed by a German U-boat and nearly sinking in March 1917, the steamer was only returned to service in January 1919. ANMM Collection ANMS0413[034]

Another infamous passenger also lurked aboard as Orsova departed chilly Liverpool. Emerging in early 1918, a highly infectious and terrifyingly virulent strain of influenza rapidly blossomed into a pandemic – known as ‘Spanish flu’. While its origins remain contested (it potentially arose in China, France or the USA), the disease did not emerge in Spain. First spanning the northern hemisphere, then leaping across the southern continents and oceans, the infection transmuted into a far deadlier form as the war drew to a close, just as millions of troops shipped home from Europe and the Middle East.

By mid-1918, medical authorities recognised that this was no normal flu. In addition to respiratory symptoms, victims suffered from fever, headaches, bodily aches and exhaustion. Formally known as ‘pneumonic influenza’ because its severe form led to pneumonia, the malady was characterised by a blue or plum colour in the patient’s cheeks, a stage that proved staggeringly fatal. Within two years the pandemic caused at least 50 million fatalities – three times the 17 million who had died over four years of war.

Scrutinising the sick list

Alarmingly for military authorities, patients most likely to die from Spanish flu were aged 20 to 40 years, otherwise healthy and predominantly male. This demographic matched perfectly the majority of sailors and soldiers who had shipped off to war.5 While exposure to the earlier or ‘first phase’ of the infection may have helped Australian troops and seamen survive the deadlier ‘second phase’, bitter experience proved that an outbreak aboard a packed troopship could have desperate consequences.6

Just a day after sailing, temporary Sergeant Kenneth Higgs of the 17th Battalion was admitted to Orsova’s hospital with influenza. The transport’s senior medical officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Glen Knight, would have carefully scrutinised each morning’s sick reports for further cases. These cards – just a small part of the voyage’s abundant records held in the National Archives of Australia – catalogued a suite of suspicious signs and symptoms, from coughs and colds to headaches and fever. Most, however, did not appear to herald pneumonic influenza.7

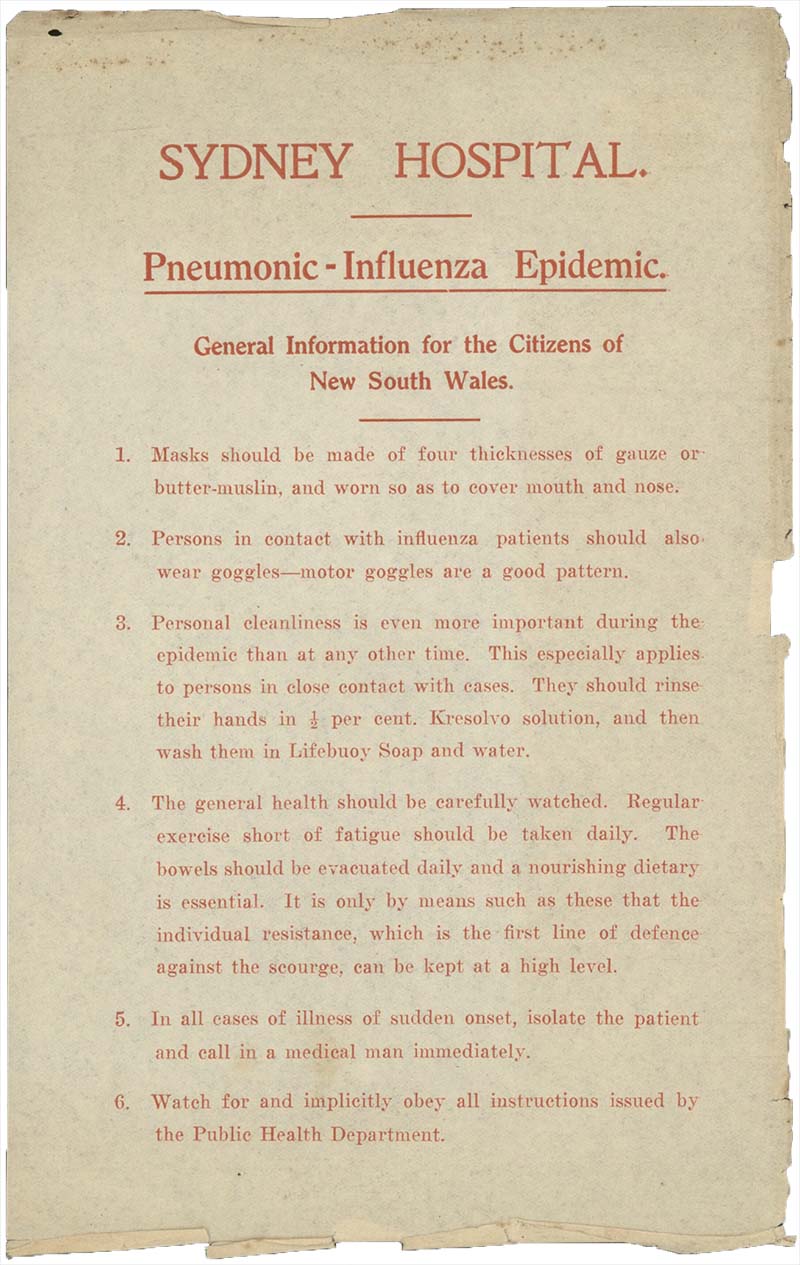

General information for the citizens of New South Wales from Sydney Hospital in response to pneumonic influenza epidemic, 1918. National Library of Australia, 37300238

Higgs recuperated and was discharged on 12 January. Just two days later, though, Private Claud Fitzmaurice of the 40th Battalion was admitted for ‘pneumonia’. His case proved so severe that Fitzmaurice was evacuated to a hospital ashore when Orsova berthed in Port Said, Egypt, on 19 January.8 The voyage newspaper, the Orsovanir, suggested that an ‘influenza hoax’ may have terminated shore leave for the remaining diggers, prompting a plentiful chorus of curses.9 Although the transport took on 70 malaria patients in Port Said, the time spent coaling apparently did not transmit a more vicious variant of influenza to the men and women aboard.

Orsova’s passage across the Indian Ocean was largely unblighted by infection, with only two further cases of influenza severe enough to require hospitalisation. Other maladies emerged, however, as befitted a population comprising mostly men who had lived hard and rough for four years. Ailments recorded in the transport’s medical files included rash, scabies, chancre (syphilis), gonorrhoea, constipation, dyspepsia, rheumatism, lumbago (back ache), headache, sore feet, malaria and enough toothache to keep the ship’s three dentists busy.10

Other aches were more emotional, however. After they crossed the equator, one battle-worn digger was moved to confess in Orsovanir that ‘Last night I saw again, after four years, the Southern Cross. There was a salty moisture in my eyes that wasn’t sea spray’.11

Irritations and detentions aplenty

Conversely, the transport’s records also reveal high-spirited and culturally insensitive hijinks in Colombo, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), where religious idols were stolen from the city’s museum. They also document a string of disciplinary hearings. Soldiers were not the only servicemen to ‘play up’ at sea; punishment records for Melbourne during Frank Bell’s time aboard reveal that his fellow stokers were regularly disciplined for cussing, gambling, drinking and attempting to smuggle alcohol aboard.12

Disciplinary powers of a different kind were invoked when the troopship approached the Western Australian coast. While stringent nationwide quarantine had kept pneumonic influenza out of Australia throughout 1918, the malady came ashore in Victoria in mid-January 1919 – about the same time as Orsova departed Liverpool. Despite the subsequent spread of ‘Spanish flu’ to other states, Commonwealth authorities allowed no relaxation in maritime quarantine.

‘Arrived Freemantle [sic] but find to our disappointment that there is a great Flu scare throughout Aussie’, remarked Frank on 10 February. Three cases of mild influenza among the passengers prompted local authorities to impose a seven-day quarantine on the transport. This order extended to detention for all 123 Western Australian troops going ashore.13 Learning that ‘no leave will be given any where & … all troops will be quarantined in their respective ports’, Frank ironically lamented that this was a ‘good welcome home after 4 years’.14

Proximity to Australia now changed both the atmosphere and the routines aboard Orsova. After leaving Fremantle, an inhalation chamber was erected aft. All soldiers and naval ratings were required to breathe in an irritant vapour of zinc sulphate, intended to disinfect their airways. The sheer number of passengers, Dr Knight reported, ensured that it ‘was impossible to spray every man daily’.15 Despite a shortage of thermometers, daily temperature parades were also instituted to detect early cases of fever that might signify influenza.

By the time HMAT Orsova moored at Adelaide’s Largs Bay on 18 February, the transport’s nominal period of quarantine had expired. Unfortunately, a fresh inspection detected two more cases of influenza. With the affected men hospitalised, another week’s quarantine was imposed on the vessel. This edict also meant that the 151 healthy passengers disembarking in Adelaide went straight into detention, as did 477 Victorian troops two days later. On arrival at Point Nepean Quarantine Station, two soldiers were again in the ship’s hospital with influenza. Only after dropping the Tasmanian contingent of 76 men in Hobart was the ship deemed free from the disease.

By the time Orsova sailed into Sydney Harbour on 25 February, the second week of quarantine had lapsed.16 Frank groaned:

So as we came thro’ the long looked for Heads, there was great speculation as to which way she would steer, round towards Watsons Bay or round to the Quarantine. Our hearts sank into the region of our boots as she steered round to quarantine.

Despite their routine of temperature inspections and inhalation treatment, the Sydney contingent – including Frank – was condemned to seven days at North Head Quarantine Station.

HMAT Orsova departed the next day to deposit its final complement of 278 men in Brisbane on 28 February. Reflecting the transport’s records – if not the frustrations of the quarantined veterans – the officer in command of the troops asserted that the ‘health of all on board was splendid, and in my experience I never before was on a healthier troopship’.17

An unhappy homecoming

That officer’s enthusiasm was not shared by the 536 Sydney personnel who landed at the Quarantine Station. As Frank remarked, it was hardly a happy homecoming. The men ‘had good cause to be indignant when we arrived at the camp & found the state of things there’. While they were willing to live in tents one more time, most were disgusted by the filthy state of the eating utensils provided at the Quarantine Station. ‘It was a good welcome back after being away 4 years to have things to eat with that I would not give to a pig’, Frank scolded.18

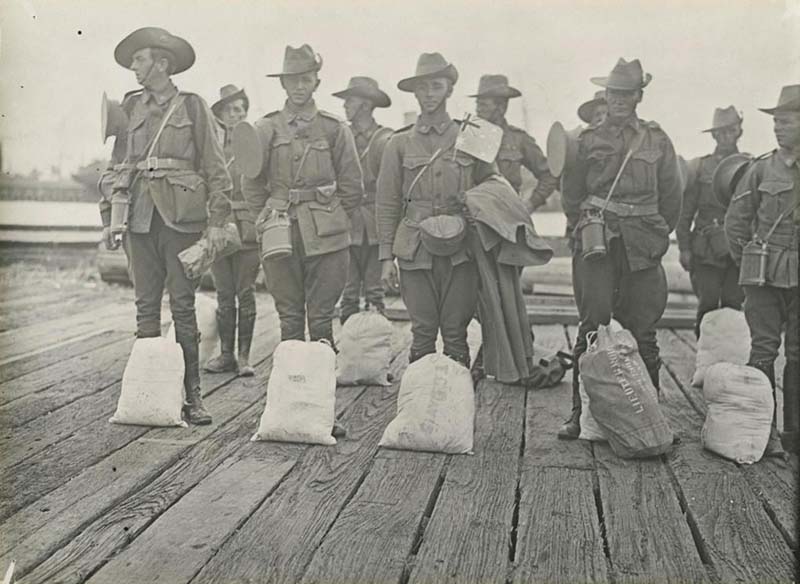

These military personnel, believed to be members of the Australian Flying Corps, were photographed by Josiah Barnes while boarding RMS Orsova for overseas service in 1916. ANMM Collection 00027607

Within hours, nearly 400 personnel who had disembarked from Orsova gathered in strength, determined to march out of the Quarantine Station and into the city. This was not the only such ‘mutiny’ prompted by returning troops quarantined at North Head due to influenza, but it represented both a serious challenge to military authority and a significant hazard to the metropolis. Although Sydney had been declared infected by ‘Spanish flu’ nearly a month earlier, it had not yet become an emergency. While cases were escalating, the disease appeared to be under control thanks to stringent civic health regulations. Not until those ordinances were relaxed in March 1919 would residents feel the full impact of the pandemic.19 A breakout from North Head by hundreds of Orsova men in late February would have posed a crisis to both public health and public order.

In the end, the men were placated by a sympathetic officer, who agreed to address their grievances. They gradually dispersed, grumbling but resigned to one more week of detention, daily temperature parades and visits to the station’s inhalation chamber. The men’s frustrations were eased by fresh food and regular rations of beer, alongside swimming and North Head’s glorious views of Sydney Harbour.

On 3 March, Orsova’s Sydney contingent was at last released from quarantine. Catching the ferry to Woolloomooloo, Frank reported to the naval base on Garden Island before being sent on extended leave. His final day in the Royal Australian Navy was 17 May 1919 – nearly six years after he enlisted. The last entry in Frank’s wartime diary eulogised that ‘now we all go our own way, but they will always look back and say, ah well, they were the best mob, the old Navy cobbers’.20 Heading home to suburban Ashfield, he survived the influenza emergency and lived until 1961.

Unfortunately for Australia, the maritime arrival of pneumonic influenza in 1919 led to what could be deemed another phase of the war, albeit against a new enemy. Throughout that year, some 15,000 Australians died from the disease – as many as were killed on service annually from 1914 to 1918. This new front line was fought in the nation’s cities and towns, and contested at border quarantines between the states. As our often-overlooked troopship records attest, this battle at sea also embroiled sailors, soldiers, nurses and civilians returning home on military transports.

References

1. Frank Bell, Diary, 21 November 1918, State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 4663/2.

2. National Archives of Australia (NAA), A6770 Bell Frank Bathurst. Frank’s transcribed service record is on ‘Discovering Anzacs’, a National Archives of Australia initiative: discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/person/774993.

3. Peter Hobbins, Ursula K Frederick and Anne Clarke, Stories from the Sandstone: Quarantine Inscriptions from Australia’s Immigrant Past (Crows Nest: Arbon Publishing, 2016), pp 180–201.

4. A Souvenir of the First Peace Voyage of the RMS Orsova (On the High Seas: Fred Werth, 1919), np.

5. NAA, MP367/1 527/21/1077.

6. G Dennis Shanks, et al, Journal of Infectious Diseases 201 (2010): 1880–89; G Dennis Shanks, et al, Lancet Infectious Diseases 11 (2011): 793–9.

7. NAA, MT1384/1 ORSOVA FEBRUARY 1918 JANUARY 1919 and MT1384/1 ORSOVA FEBRUARY 1919.

8. NAA, MT1384/1 ORSOVA JANUARY 1919 PART 2.

9. The Orsovanir (sn: Orsovanir Press, 1919), p 9.

10. NAA, MT1384/1 ORSOVA FEBRUARY 1918 JANUARY 1919 and MT1384/1 ORSOVA FEBRUARY 1919.

11. Orsovanir, p 10.

12. NAA, A7111 HMAS MELBOURNE 1915.

13. [Troopship records, 1914–1918 War] Orsova: Liverpool January 1919 for Australia, Australian War Memorial (AWM), AWM7 ORSOVA 6.

14. Bell, Diary, 10 February 1919.

15. AWM, AWM7 ORSOVA 6.

16. Bell, Diary, 25 February 1919.

17. NAA, MT1384/1 ORSOVA JANUARY 1919 PART 2.

18. Bell, Diary, 25 February 1919.

19. Peter Hobbins, ‘An Intimate Pandemic: The Community Impact of Influenza in 1919’, Royal Australian Historical Society, rahs.org.au/an-intimate-pandemic-the-community-impact-of-influenza-in-1919/.

20. Bell, Diary, 17 May 1919.

Dr Peter Hobbins is Principal Historian at Artefact Heritage Services in Sydney. Over 2018–19 he coordinated a Royal Australian Historical Society project to document community histories of the 1918–19 influenza pandemic.