Yachtsmen competing in the 1998 Sydney to Hobart race did not expect to sail right into a hurricane, yet on Saturday 26 December as the fleet travelled south, that’s exactly what happened.

On Christmas Day, a high pressure system directing warm north-easterly winds over south east Australia started moving towards a cold front approaching Tasmania from the Southern Ocean. Late on the 26th, differences in the two air masses generated a highly intensified east coast low at the start of the Bass Strait – equivalent to a force 12 hurricane storm. This storm brought forth 10–15 metre swells and 60 knot winds, causing havoc among the fleet.

Overnight, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) began preparing for the coordination of Australia’s largest peacetime search and rescue operation to date. Naval Crewman Shane Pashley, from Fleet Air Arm 816 Squadron, was one of the many naval and civilian personnel involved in the week-long operation.

I just looked back into the aircraft and thought I cannot believe I’m about to do this.

Aboard an S-70B-2 Seahawk helicopter – ‘Tiger 75’, Shane and his crewmembers were on their way back to Nowra at 10 pm on the 28th of December for a night’s rest. Tracking yacht distress signals and spotting those in disarray, the Seahawk helicopter picked up one last signal on the night of the 28th from a Winston Churchill crewmember in a life raft. This was significant as communication with those on-board the historic sloop had been considered lost.

Winston Churchill heading out from Sydney Harbour for the 1998 race. Image courtesy John Stanley

John Gibson and John Stanley, who were in the life raft, had successfully attracted the attention of a P3 Orion Air Force maritime surveillance aircraft with their pocket flash torches. This aircraft then relayed the signal on to the Seahawk. Shane and his crewmembers turned around, flying into perhaps one of the most dangerous rescue operations of their entire naval careers.

There were 36 knot winds and 15–18-metre seas. Flying in an aircraft 80–100 miles off the coast when it’s pitch black and cloudy, you can’t see the hand in front of your face. When we got down closer to the ocean and put the search lights on, it was like a washing machine.

We could see there was two people in a life raft and that’s all we could tell. We couldn’t communicate with them, it was pretty dark, a lot of spray and a lot of movement. One minute they would be 20ft below us, and then one minute they would be 50ft below us, and moving away from us. There wasn’t really much for me to do except to go into the life raft and pick them out …

I connected my harness up, I’m sitting in the doorway looking down, and you could see straight down into the light but when you looked out it was just black, there was just nothing out there. You couldn’t see anything from about 50ft away. We now had two maintainers with us in the back seat, but they weren’t on intercom, and they didn’t really know what was going on.

The Tiger 75 crew standing outside Government House in Sydney 1999, after receiving Bravery Citations for their involvement in the 1998 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race search and rescue operation. Left to right: Co-Pilot Lieutenant Nick Trimmer, Naval Crewman Petty Officer Shane Pashley, Pilot Lieutenant Commander Rick Neville, Winch Operator Lieutenant Aaron Abbott. Image courtesy Rick Neville

During the rescue operation Tiger 75 landed on HMAS Newcastle in order to refuel. While landing, the helicopter exceeded its pitch and roll limits due to the extreme weather conditions, and two maintainers had to be sent out to the ship in order to inspect the aircraft. These two individuals then crewed with Tiger 75 in the evening of the 28th on an expected journey directly back to Nowra.

When it was time for me to go down, there was just that moment I always remember, when I swung around outside the door of the aircraft and I just looked inside, and just that dull red glow of the overhead lights, and the maintainers looking at me like, ‘What are you doing?’ ‘Where are you going?’

What came next was perhaps the most miraculous highline transfer of the entire 1998 rescue operation.

Shane’s descent towards the life raft was controlled by winchman Aaron Abbot. From the Seahawk’s rear control console Aaron was also in charge of maintaining the helicopter's position over the rapidly moving life raft, constantly making adjustments to their position, and drastically pulling Shane through the air on the winch wire.

One minute the life raft is 50 ft below me, then 30 ft behind me because it just picks up onto the next wave. So the guys are chasing the life raft around trying to get me into it. I’m spinning around going night blind…

In the end they got me into the water pretty close to the raft, but now I’m in this big ocean trying to swim towards this life raft as its moving, while dragging the winch cable behind me as well. I got to the life raft, and I thought cool I’m safe now. I pulled myself over the side, and went straight back into the ocean again. There was no floor on the life raft.

Tiger 75 being latched down to the flight deck of HMAS Melbourne after landing during a big swell, 1998. Image courtesy Rick Neville

John Stanley, John Gibson, John Dean, Mike Bannister and Jim Lawler had boarded their life raft at 4 pm on the 27th, when it was flipped by a rogue wave. Worried they would run out of oxygen, the crewmembers decided to cut a small hole for air in the life raft’s upturned floor. Not long after, a second rogue wave rotated the life raft right-side-up, and in this motion John Dean, Mike Bannister and Jim Lawler were swept away.

The winch wire then started wrapping around me as we were moving, and I was starting to get a bit concerned. I eventually got myself into a position on the side of the life raft to hold on, but the roaring of the wind and the noise of the aircraft made it a bit difficult.

I could see that the guys were moving, and it wasn’t too cold so I wasn’t worried about hypothermia.

When deploying the life raft drogue, John Gibson’s hand was severely cut and rendered immobile. Due to Gibson’s injury it was decided that he was to be winched first.

I put the lifting strop around the top of Gibbo’s head, and luckily we got it all the way on him, because that’s when the aircraft had its flight control failure. The [helicopter’s] RADALT automatic hover control tripped due to the severe conditions, and we got pulled out of the life raft fairly unceremoniously, straight into a 40ft wave. It was a very intense reefing …

While the guys were fighting to get the aircraft back under control, I was fighting to hang on to Gibbo as we got smashed into wave after wave …

I don’t even know how long it took, everything happens in a blink of an eye in an accident, but they reckon we were in the water for a good 10 minutes or so. I was just hanging on.

Naval personnel involved in the 1998 rescue and race survivor John Stanley at the museum's opening of Challening, thrilling, racing: Sydney to Hobart 75 years. Left to right: Warrant Officer Shane Pashley, John Stanley, Commander Rick Neville and former Commanding Officier of HMAS Newcastle Steve Hamilton. Image Andrew Frolows/ANMM photographer

After getting back to the aircraft the crew deemed it too risky for Shane to go back into the water again due to the aircraft malfunction. A strop was instead sent down on its own for John Stanley. John recalls the moment this happened:

They sent the wire down, which I was quite happy with, and I put it on but I didn’t realise I had put my arm through the life raft. So as they are hauling me up I’m taking the life raft up with me and I thought God this is bloody disastrous. So I put my hands in the air and went back into the ocean after I was about 30ft up.

Shane and the Seahawk crew were unaware as to why John had dropped back down.

We thought he was really tired or injured. So we said we’ll give it one more go, and if he can’t get the strop on himself I’m gonna have to go back down.

John was successful on the second attempt, pulling himself up after 30 hours in the life raft, and with broken ankle and ripped tendons.

After being lifted into the aircraft, John Gibson and John Stanley’s immediate concerns turned to the wellbeing of their fellow crewmembers. Gibson was adamant he knew the location of the three others swept from their life raft the day before – urging the Seahawk crew to continue the search.

At this point both the Winston Churchill crewmembers and Seahawk personnel were unaware that those in the second life raft had been picked up on the same day. Given Gibson and Stanley’s injuries, and the distance yet to travel to Merimbula, the Seahawk crew prioritised getting those rescued to land for medical attention, passing Gibson’s data on to a Seaking helicopter that was still operating in the area.

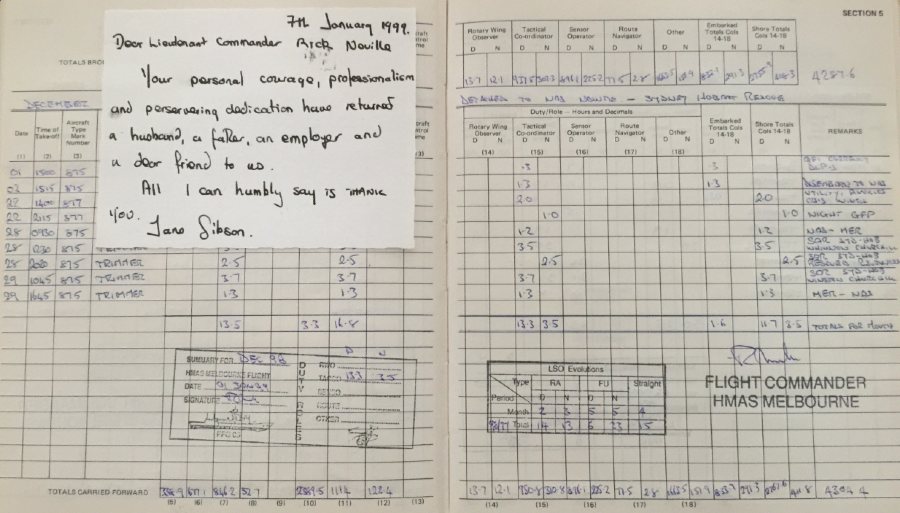

Tiger 75 flight log from the 1998 Sydney to Hobart search and rescue operation, includes a heartfelt letter of thanks to the crew from Jane Gibson, wife of John Gibson. Log courtesy of Rick Neville

1998 remains the most tragic year in the history of the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. Six sailors lost their lives, including John Dean, Mike Bannister and Jim Lawler from the Winston Churchill. Thanks to the actions of Shane and other rescue crew, 55 sailors were pulled from the tumultuous seas. Only 44 yachts finished the race, 60 having to pull aside and five of which – including Winston Churchill – sunk. The resulting inquiry recommended drastic changes to race rules and safety provisions. Tiger 75 stands as a powerful object in the museum collection, both as a symbol of the RAN’s search and rescue capability, and as an epitaph for those lost in the tragedy of 1998.

Shane Pashley and the rest of the Tiger 75 crew were awarded Group Bravery Citations following the 1998 rescue, something he reflects upon with admirable humility.

In this job we practice doing this sort of stuff all the time, we practice winching, we practice search and rescue, but to do one it sort of brings it all home that this is what you’ve trained for. Sydney to Hobart was a big one. It was great to be part of the biggest, most outrageous rescue in maritime history.

Challenging, Thrilling, Racing: Sydney to Hobart 75 Years is open at the museum until 28th February. Charting the history of the race through a photographic timeline and selection of keynote objects, the exhibition takes a particular focus on the personal stories surrounding the blue water classic, ranging from the memories of Shane Pashley, to accounts of those involved in the very first race in 1945.