Maritime archaeologists from the museum and its long-term research partner Silentworld Foundation recently collaborated on a project to uncover the history of the paddle steamer Herald. Dr James Hunter, Kieran Hosty and Irini Malliaros gained new clues about its demise using photogrammetric 3D recording.

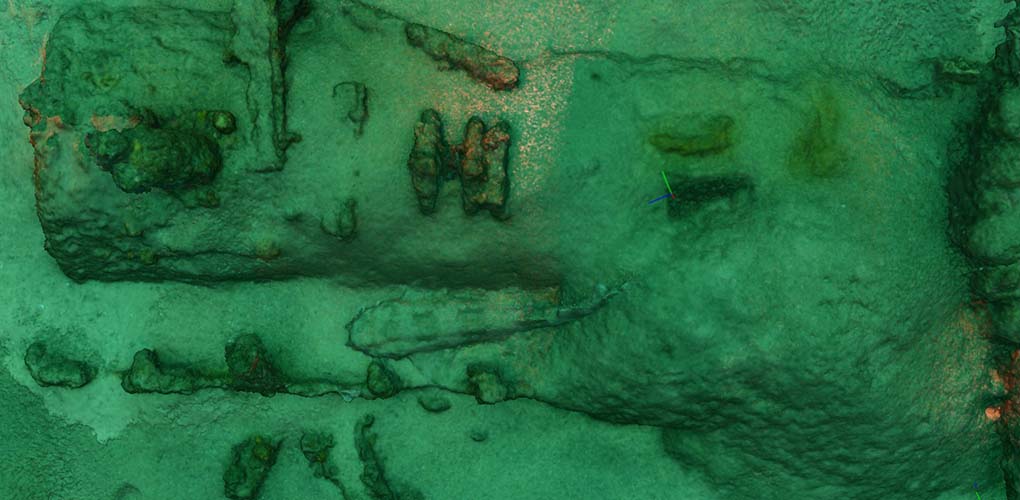

Medium-resolution digital model of the PS Herald wreck site produced from 3D photogrammetric data collected during the 2019 survey

In mid-March, the museum's Dr James Hunter and Kieran Hosty teamed up with fellow maritime archaeologists Irini Malliaros and Paul Hundley, from the museum’s supporter and research partner Silentworld Foundation (SWF), to undertake a 3D photogrammetric survey of the shipwreck site of the paddle steamer Herald, located at the entrance to Sydney Harbour. The survey is part of an ongoing collaborative project between the museum and SWF called The Maritime Archaeology of Sydney Harbour.

It uses Photogrammetric 3D Recording (P3DR) to document and interpret historic shipwreck sites within the harbour, which provides the benefit of maritime heritage preservation through digitisation. The project is also part of a broader initiative to test the utility of P3DR on shipwrecks located in low-to-moderate water clarity at depths exceeding 20 metres. The March visit was the second time the team attempted a P3DR survey of Herald (see Signals issue 117), but the results proved far superior due to improvements in equipment and technique.

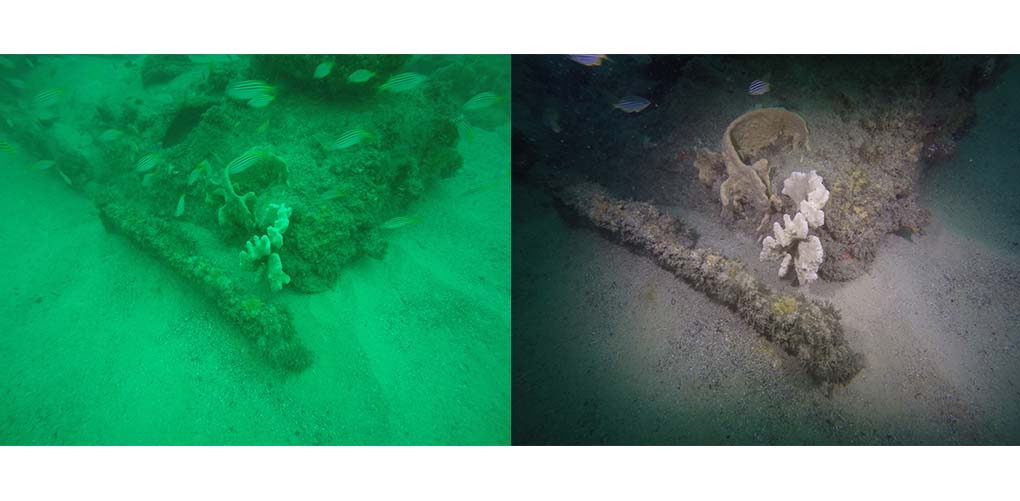

James Hunter conducts a photogrammetric survey of Herald’s starboard boiler. A lighting array was used to illuminate the wreck site and resulted in imagery that was a vast improvement over photographs collected by the team in 2016. Image Irini Malliaros

A ‘well-known and fine paddle-wheel steamer’

Herald was a double-ended, side-wheel paddle steamer with a lengthy and celebrated history significant to Sydney, if not Australia as a whole. Its iron hull was assembled in three sections at the shipyard of Randolph, Elder & Co in Govan, Scotland, in 1854, loaded aboard the clipper barque Queen of the Isles in Glasgow, and shipped to Sydney. The engine and boilers, also built by Randolph, Elder & Co, accompanied the hull. Their designer, John Elder, was a pioneer in nautical engineering who invented the world’s first successful marine compound steam engine (also in 1854).

The only known photograph of PS Herald, showing the paddle steamer in Sydney Harbour during the latter half of the 19th century. Image Stanton Library, North Sydney

Assembled near the Pyrmont Gas Works on Darling Harbour and completed in May 1855, Herald was one of the earliest iron-hulled paddle steamers built in Australia.1 Its hull, assembled from iron frames and carvel-joined iron plates, measured 22.8 metres in length, with a breadth of 3.9 metres and depth of 1.7 metres. Herald’s carrying capacity was 22 net tons (41 tons gross), and its engine generated 22 horsepower for its two side-mounted paddlewheels.

Herald was a double-ended, side-wheel paddle steamer with a lengthy and celebrated history significant to Sydney, if not Australia as a whole

Following its launch, Herald commenced service for the North Shore Steam Ferry Company, operating mainly as a passenger ferry, but also towing sailing ships to and from Sydney Heads. Although Herald had an excellent operating record and reputation, the North Shore Steam Ferry Company went into dissolution in 1859, and the ‘well-known and fine paddle-wheel steamer’ was put up for sale at auction in September of that year.2 The new owners, Messrs Smith and Evans, continued to operate Herald as a ferry on the same routes, but found it less profitable than they had hoped, and consequently rented it under charter to Captain George Hall and Sons. Captain Hall was so impressed with the vessel that he purchased it in November 1860 and nominated his son James Henry Hall as master and operator. The younger Hall held this position until his untimely death at the age of 24 in 1870.

Command of Herald then reverted to his father, who was the steamer’s master for the next 11 years and participated in several rescues within the harbour during that time. So prolific were his lifesaving exploits that he was awarded a ‘massive colonial gold ring’ by the city’s Cosmopolitan Club in 1876 for ‘saving about forty lives since [assuming] … command of the Herald’.3 He was also awarded a silver medal by the Shipwreck Relief Society of New South Wales in 1879 for rescuing the captain of the brig African Maid and his wife, when both accidentally fell overboard in December 1877. Herald was the vessel used in the African Maid rescue, and was presumably employed in most, if not all, of the others.

Tragically, the man who had saved so many lives at sea accidentally drowned in the Yarra River on 4 April 1881 while visiting a friend in Melbourne. In a bizarre twist, Herald had been bought at auction just two days earlier by Charles Livie, who employed Hall’s surviving son, George Hall Jr, as its master. The younger Hall remained in command of the steamer when it was again put up for auction and purchased by John Blue only seven months later in October 1881. Blue, the son of ex-convict and ferry operator William ‘Billy’ Blue (for whom the Sydney locality Blues Point is named), transferred title to his sons Samuel and George Ernest in August of the following year.

Herald’s demise

Under new ownership, Herald’s role expanded to include other operating areas and tasks. During the latter half of 1881, the vessel transported supplies and equipment, including ‘about five tons [of] machinery’ stowed on its deck, from Sydney to Botany Bay for the construction of a bay bridge associated with the Illawarra Railway.4 Despite having to endure ‘heavy seas and a strong south-west wind’ while also towing two punts and a boat, the heavily laden steamer delivered the material safely.5

During the final two years of its life, Herald no longer functioned as a passenger ferry, but instead transported cargo throughout the harbour and towed sailing vessels to and from Sydney Heads. In this latter role the paddle steamer met its end ‘in a most extraordinary and unexpected manner’ in the early hours of 1 April 1884.6 Herald, with George Hall Jr at the helm and James Francks serving as fireman, had gone to the Heads to meet the schooner Malcolm and take it under tow. While lying ‘between 200 and 300 yards’ (180 to 270 metres) off North Head, the steamer’s starboard boiler suddenly ruptured with a sound ‘as loud as [a] pistol shot’, and the hull rapidly filled with water.7 Hall later testified that both boilers had been thoroughly cleaned and tested to 45 pounds of steam two months before the incident, and they contained 40 pounds of steam and their proper quantity of water when the rupture occurred.8

The steamer’s starboard boiler suddenly ruptured with a sound ‘as loud as [a] pistol shot’ and the hull rapidly filled with water

Hall attempted to steer Herald for the reef at South Head, presumably in an effort to beach the vessel, but the rapid ingress of water soon caused the hull to heel over enough that all steerage was lost.9 Francks launched the steamer’s dinghy shortly before Herald foundered. Both men were able to scramble aboard the dinghy, and the crew of the passing steamer Kiama later picked them up. Hall subsequently testified before the Marine Board that it took three-quarters of an hour for the vessel to sink, and both he and Francks hypothesised that the rupture occurred at the bottom of the boiler and forced out the bottom of the hull.10

In a strange coincidence, Herald’s loss occurred almost three years to the day after George Hall Sr drowned in the Yarra River.

The PS Herald shipwreck site

Although gone, Herald was far from forgotten, and remained in Sydney’s – and particularly the North Shore’s – public consciousness for decades after its loss. Articles about the vessel appeared in local newspapers in 1909 and again in 1950, and a parade float was specifically constructed in its honour in 1938 for North Sydney’s sesquicentenary celebrations. The precise location and fate of the steamer itself, however, remained a mystery until 3 January 2013, when local shipwreck researchers Scott Willan and Andreas Thimms of NSW Wrecks (www.nswwrecks.info) discovered its wreck site in 27 metres of water near North Head. Willan pinpointed the wreck’s location after analysing magnetometer data collected by Australia’s Defence Science and Technology Organisation in 2000.

At the time of discovery, an area of about three by four metres square was exposed above the seabed and comprised the tops of Herald’s two boilers, as well as the upper surface of its engine. The paddlewheel shaft and one hub were also visible, and the shaft had shifted approximately one metre to starboard of the vessel’s centreline. The shape of the bow and stern were barely perceptible, but enough of the stem and stern posts were exposed for Willan and Thimms to obtain an overall preserved length of 23 metres and confirm the wreck site’s identity. Maritime archaeologists from the then-New South Wales Heritage Branch (now Heritage and Community Engagement, Office of Premier and Cabinet) and the Australian National Maritime Museum inspected Herald on 7 January 2013.

2019 photogrammetric survey

Herald was first surveyed via P3DR by maritime archaeologists from the museum and Silentworld Foundation in November 2016. Parallel measuring tapes were installed at regular intervals across the site to serve as reference points, and digital imagery was acquired primarily in video form, with some still imagery also collected. Although the survey resulted in more than 100-per-cent coverage of Herald’s visible components, most of the video footage was shot from plan view (that is, overhead). In addition, the wreck site was obscured by a combination of schooling fish, such as large numbers of eastern nannygai (Centroberyx affinis), and poor water clarity. This resulted in imagery that ultimately could not be aligned and combined into an accurate 3D composite model.

In the case of Herald, the 3D virtual models have provided an opportunity to closely and methodically inspect the entire wreck site within a significantly expanded timeframe

For the 2019 survey, each diver who entered the water was equipped with a camera and assigned a specific area of the site to photograph. Imagery collected for P3DR purposes comprised 12-megapixel digital stills captured at two-second intervals. Photographs were taken from multiple perspectives and distances, rather than from plan view and fixed distance, as occurred in 2016. The measuring tapes used during the earlier survey were abandoned because they required too much valuable bottom time to install and were often moved or altered by current and surge. Lighting arrays were added to two cameras, which illuminated site features effectively and revealed their natural colour.

A lighting array was used to illuminate the wreck site and resulted in imagery that was a vast improvement over photographs collected by the team in 2016. Imagez Irini Malliaros and James Hunter

The refined methods and equipment, as well as better overall water clarity, resulted in imagery far superior to that collected in 2016. During data processing, more than 80 per cent of the collected images aligned successfully, generating a good-quality 3D model of the Herald wreck site. One major difference between the surveys was the elimination of schooling fish as a mode of failure during the modelling process. In 2016, the frame rate produced from digital video was frequent enough that schooling fish did not appear to move between individual images. As a consequence, the modelling software was largely unsuccessful in differentiating between the wreck site and the fish swimming around it, and could not align enough images to produce a useable 3D model. Images acquired at two-second intervals in 2019, by contrast, allowed for fish movement to create enough disparity between images that the software was able to identify and remove schooling – and even individual – fish. The notable exceptions were two wobbegong sharks (Orectolobus sp), which lay largely motionless among the boilers and were modelled along with the wreck site.

Close up detail of the 3D model, complete with resident wobbegong shark. Image Irini Malliaros and James Hunter

Herald’s loss re-examined

Herald’s 3D models have already proven useful in identifying processes that contributed to the formation of the shipwreck site. The overall appearance of the site has not changed markedly since its discovery in 2013. The tops of the boilers, upper surface of the engine and paddlewheel shaft are all still visible, while the tops of the stem and sternpost appear to have been buried by shifting sand. A line of preserved midships hull plating is visible just above the seabed next to both boilers, and approximately corresponds to the level of Herald’s waterline. The remainder of the lower hull is buried, and likely still intact and very well preserved. By contrast, the hull plating above the waterline is no longer visible, and over time was probably weakened by corrosion and other natural processes until it collapsed to the sea floor and was eventually buried.

An advantage of P3DR is that it allows shipwrecks to be viewed in their entirety and inspected more closely – something that is not always easy to do in low-visibility environments with limited bottom time. In the case of Herald, the models have provided an opportunity to closely and methodically inspect the entire wreck site within a significantly expanded timeframe. This has revealed a number of clues that might otherwise have gone unnoticed and/or unrecorded.

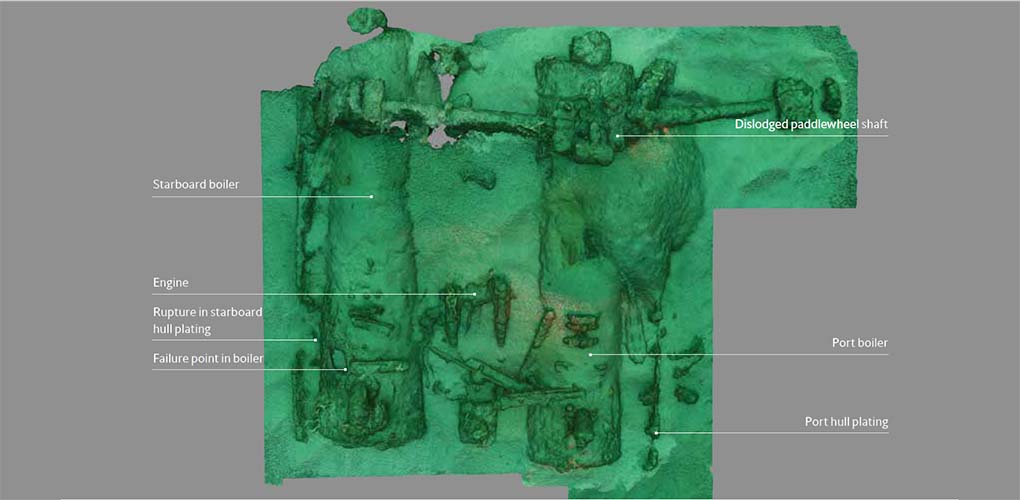

Annotated plan view of the Herald 3D model, showing features of interest. The wobbegong shark can also be seen at image right, between the port boiler and port hull plating. Image Irini Malliaros and James Hunter

For example, a gap in the hull plating next to Herald’s starboard boiler was initially thought to be the result of corrosion. A review of the 3D models, however, has revealed the breach is approximately oval in shape, and that the edges of the hull plating surrounding it are bent slightly outwards. Further, the breach is located very close to a smaller, oval-shaped hole (also originally thought to be corrosion related) located on the upper surface of the boiler near its forward end. After considering the 3D imagery, the team now believes the latter opening is the point where the starboard boiler failed on the morning Herald sank, and the large breach in the plating at the waterline is where the resulting blast ejected one or more boiler fragments through the steamer’s hull. These findings argue against existing historical accounts of the incident, which state the failure occurred along the bottom of the boiler and caused a breach in the bottom of the hull.

Other intriguing – and potentially important – clues to Herald’s demise are the location and condition of the paddlewheel shaft. While it was already known that the shaft was dislodged and lying about one metre to port of the vessel’s centreline, the 3D models have revealed it has also been completely removed from its mountings and deposited some two metres aft of the engine. Further, the shaft has clearly been bent into a shallow ‘V’ shape. Taken together, these attributes reveal the shaft was subjected to tremendous force(s) that distorted and removed it from its original context.

This screen capture of Herald’s starboard boiler reveals the difference in colour and detail that results from the use of camera-mounted lighting arrays. It also shows damage to the streamer caused by the failure of its starboard boiler on 1 April 1884. Image James Hunter

The exact cause of the damage remains an open question, but an intriguing possibility is that the paddlewheel shaft was directly affected by the rupture of Herald’s starboard boiler, which originally was located underneath it. The force of the blast could have dislodged the paddlewheel mechanism and either pushed the shaft towards the stern at the time of the rupture, or loosened it enough that it broke free and shifted aft when Herald struck the seabed. Another alternative is that the shaft was damaged and moved in consequence of a large anchor dragging through the site, but the relative lack of damage to the rest of the wreck – including the boilers and engine – seems to argue against this scenario.

Herald provides an excellent example of the ways in which P3DR may be used to archaeologically document and interpret a shipwreck site – even one that is relatively small and largely buried. The team continues to review the imagery collected during the March visit, and intends to conduct additional photogrammetric surveys of the site in future, with the goal of revealing more about this little steamer and its larger-than-life story.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Paul Hundley of Silentworld Foundation for piloting their research vessel, Maggie III, and providing invaluable surface support during the P3DR survey of Herald.

References

1. Parsons, R 2000, Early Steam Ships in Australia, Ronald Parsons, Goolwa.

2. The iron-built steamer Herald’, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 September 1859, p 10.

3. Australian Town and Country Journal, 19 February 1876, p 26.

4. ‘The Illawarra Railway’, Telegraph and Shoalhaven Advertiser, 25 August 1881, p 2.

5. Ibid.

6. ‘Shipping’, Mercury, 8 April 1884, p 2.

7. ‘Marine Board: Foundering of the S Herald’, Evening News, 8 April 1884, p 3.

8. Ibid.

9. ‘Shipping’, Mercury, 8 April 1884, p 2.

10. ‘Marine Board: Foundering of the S Herald’, Evening News, 8 April 1884, p 3.

Further articles about photogrammetric recording in Signals

- Hosty, K 2017, ‘Lady Darling and PS Herald: new technologies help to record old wrecks’, Signals 117, pp 23–27.

- Hunter, J, Hosty, K and Malliaros, I 2018, ‘Piecing together a puzzle: photogrammetric recording in the search for Cook’s Endeavour’, Signals 125, pp 14–19.

- Hunter, J and Woods, A 2018, ‘Imaging Australia’s first naval loss: the 2018 photogrammetric survey of submarine HMAS AE1’, Signals 124, pp 2–7.