Eleven years ago today, the Australian government made a long-awaited national apology to the thousands of former child migrants whose lives were impacted by government-sponsored child migration schemes.

The 11th anniversary of the apology to former child migrants

Eleven years ago today, then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd delivered a national apology to Forgotten Australians and former British child migrants at Parliament House in Canberra. Mr Rudd acknowledged:

… the particular pain of children shipped to Australia as child migrants – robbed of your families, robbed of your homeland, regarded not as innocent children but instead as a source of child labour. To those of you who were told you were orphans, brought here without your parents’ knowledge or consent, we acknowledge the lies you were told, the lies told to your mothers and fathers, and the pain these lies have caused for a lifetime. To those of you separated on the dockside from your brothers and sisters; taken alone and unprotected to the most remote parts of a foreign land, we acknowledge today that the laws of our nation failed you. And for this we are deeply sorry.

Prime Minister Kevin Rudd apologises to Forgotten Australians and former child migrants, Canberra, 16 November 2009. Courtesy Fairfax Photos

Political developments and public awareness

Since the apologies, a range of political developments have occurred in Australia and the UK. This includes the establishment of a £6 million Family Restoration Fund for former child migrants, the launch of the Australian Find & Connect web resource, the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, the Northern Ireland Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry, the National Inquiry into Historical Child Abuse in Scotland, the ongoing Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse in England and Wales, and a landmark $24 million settlement in the class action against the Fairbridge Farm School in Molong, New South Wales.

There has also been a proliferation of scholarly works and memoirs about child migration, as well as the acclaimed Jim Loach film Oranges and Sunshine. All have contributed to a greater public awareness of the British child migration schemes over the past decade.

Reflections from former child migrants

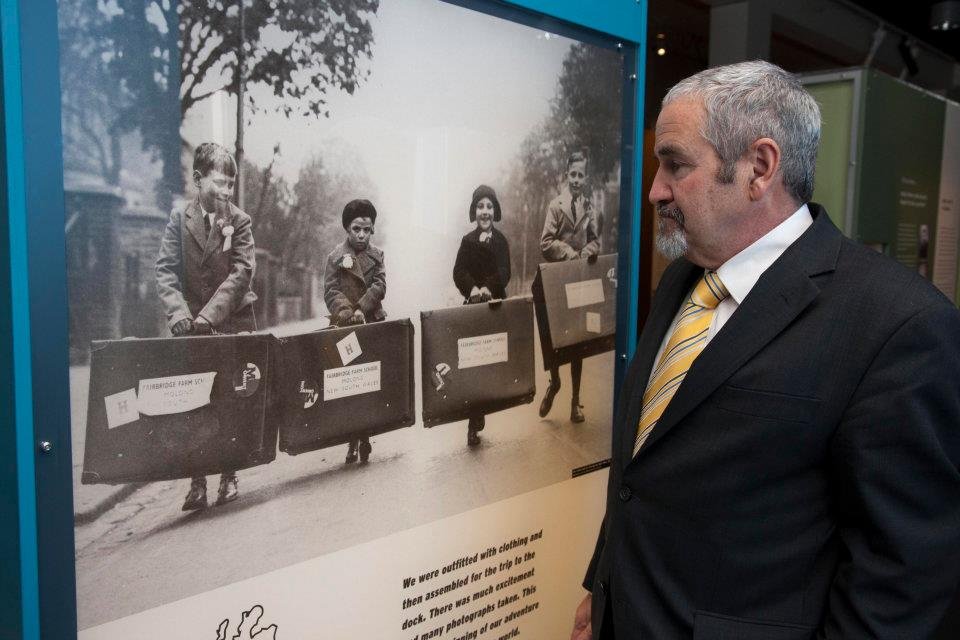

Hugh McGowan views the On their own exhibition, 2011. Courtesy Museums Victoria

On the 10th anniversary of the national apology, I asked two former child migrants who were involved with On their own to reflect on the day.

Hugh McGowan was sent from Glasgow, Scotland, to the Presbyterian Church’s Dhurringile farm near Tatura, Victoria, in 1961. Hugh was 13 years old, and unbeknownst to him, Dhurringile was one of five Australian institutions that had already been blacklisted by the UK Home Office in 1956.

Hugh says:

At the time of the apology I could not help feeling a little cynical. It left me with the view that we child migrants were attached to the apology as an afterthought. I think the federal government was apologising to the Australian children who were incarcerated in children’s homes throughout Australia. We child migrants felt we deserved a separate, more focused apology. Even now the federal government is loathed to accept fundamental responsibility for the damage caused to children who were plucked from children’s homes in the UK and sent to badly run homes here. Remember it occurred because the Australian government asked for the children.

Yvonne Radzevicius, also from Glasgow, was sent to Nazareth House in Geraldton, Western Australia, in 1953. For Yvonne, who was 10 years old at the time, ‘My lasting thought of Great Britain was being herded like cattle to board the New Australia. The nuns told me my parents were dead and I had no brothers or sisters’.

In 1979, Yvonne returned to Scotland and was shocked to discover that her mother was alive and she had three sisters and two brothers. Sadly Yvonne’s mother died only two weeks after they were reunited in 1980. As a result Yvonne had a breakdown and spent the next two years in psychiatric care.

Yvonne Radzevicius with a photograph of her mother Bridget, 2010. ANMM Collection

Yvonne says:

While the apologies took a long time coming, I feel it would have seemed more sincere if the politicians from Britain and Australia had travelled to the former child migrants with deliverance of the apology. Those who were able to travel heard it firsthand. Others sat in the sun or listened on television and it wasn’t as personal as I would have appreciated. But the admission of the wrong of the ‘scheme’ was a consolation to me after the lengthy time waiting for people to believe in our story.