A recent gift to the museum is a small masterpiece of Victorian-era manufacturing that evokes a bygone era when Sydney was a vibrant working seaport.

Today an oyster bar has connotations of elegance and refinement, with plush chairs, fine dining and attentive waiters – but in the 19th century, its ambience was quite different. Oyster bars lined many of Sydney’s main streets and were mostly the haunts of the working men of the city’s seaport. Oysters then were common fare.

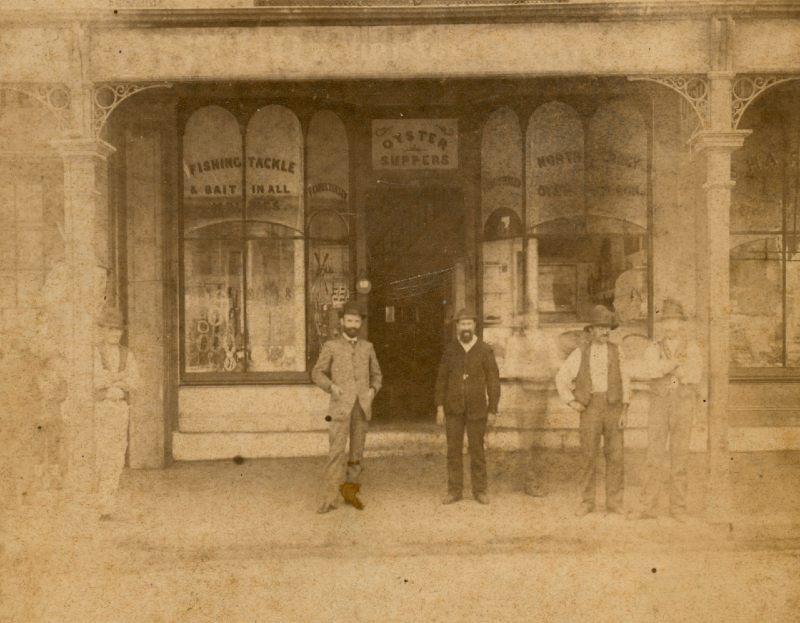

Evidence suggests that some saloons were busy commercial premises selling their mostly male customers a range of sea-related goods such as fish for the home table, prawns, bait, even fishing hooks and tackle.

A fascinating artefact recently given to the National Maritime Collection evokes something of the oyster bars of old Sydney and reminds us of the entrepreneurial spirit of a 19th-century immigrant, Danish sailor Frederick Christensen.

Harpoons, lances, hooks, flies, sinkers and lures: the paraphernalia of fishing proudly displayed in the Bartleet and Sons case. ANMM Collection Gift from Christine Fraser. Image Andrew Frolows

A refined yet impactful piece, this encyclopaedic display of fishing equipment is artfully arranged in a glass-fronted timber showcase. It was made by William Bartleet & Sons, the needle and hook manufacturer established in 1750 in Redditch, England, then the world centre for the manufacture of such goods.

The piece was designed as a fine promotional item for display at international trade fairs, and in the early 1890s it was exhibited by Frederick Christensen in his oyster saloon in George Street in Sydney’s Rocks area, on the western bank of Sydney Cove. He and his neighbours – grocers, fruiterers, shipping butchers, glass and earthenware merchants, clothiers and outfitters, bootmakers and publicans – all serviced a bustling port population.

Christensen’s premises would have been a busy focal point for mercantile life, with ships, crews, passengers, wharf workers, merchants, traders and travellers coming and going all day, every day. All needed feeding and supplies.

Frederick Christensen first visited Sydney in the 1860s as an able seaman. In May 1863 he was convicted of desertion in the Water Police court and sentenced to six weeks hard labour in gaol.1 Through the 1860s he appears on crew lists on vessels arriving in Sydney until his marriage in 1870 to Mary Anne Tubberdy (or Tauberdy), an assisted immigrant from Ireland.

From 1875 Christensen appears in directories in northern George Street, Sydney, as an oyster dealer and fishmonger – one of 25 in the city’s streets. Sold freshly shucked or unshucked, Sydney rock oysters (Saccrostrea glomerata) or mud oysters (Ostrea angasi) were harvested from the intertidal zones of the harbour and the waterways, mudflats and mangrove swamps around Botany Bay, the Cooks and Georges rivers and further afield.2 These fertile oyster beds, which had been supplying people for tens of thousands of years, were disappearing by the late 19th century as a result of population spread, disease, harbour and river pollution and over-harvesting – the shells for quicklime for construction mortar and the oysters for food.

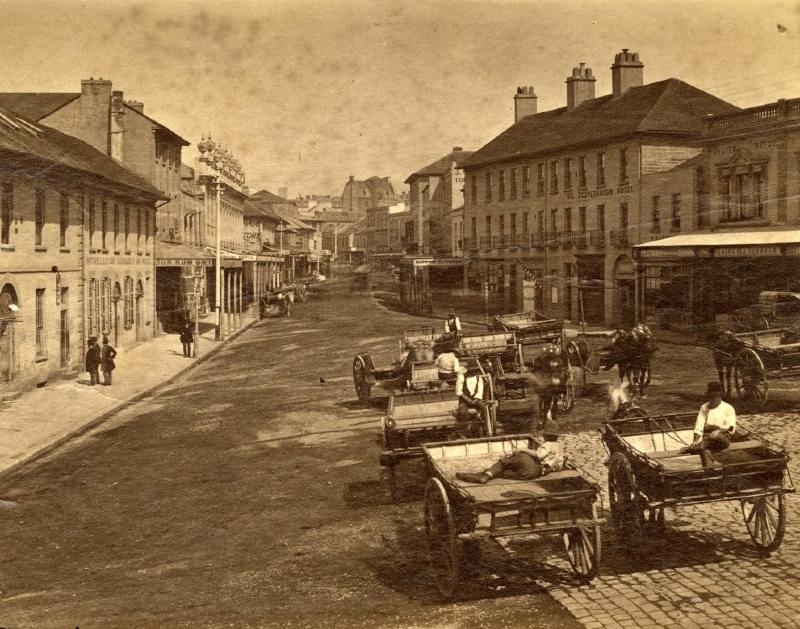

Lower George Street, Sydney, c1880. Image courtesy Property NSW

When Christensen established his business in the early 1870s, a new fish market had opened at Woolloomooloo Bay, and he maintained a close commercial relationship with it. He owned boats and frequently advertised hauls of fresh prawns and bait in the Sydney Morning Herald.

By 1883 he was a regular at the early morning markets, and was named by a writer for the Australian Town and Country Journal as among the 75 per cent of foreigners – primarily Hungarians, Jews, Greeks and Italians – who would jostle with the auctioneer for species such as Tuggerah whiting, schnapper, squires, sea mullet, jewfish, garfish, flounder and black bream. Their market haul would then be ‘basketed away … to sell at a considerable profit several hours later’.3

In 1890, a newspaper article named Christensen’s of George Street as the place to go for specialised equipment and proper hooks for shark fishing, which it described as ‘a sport for emperors’. A fishing party mentioned in the article caught species including blue pointer, grey nurse and tiger sharks with hook, harpoon and lance.4 While shocking today, in the 1880s, day trips to fish for shark and snapper were growing in popularity and Christensen was involved in such excursions, selling tickets, bait and Bartleet hooks and tackle.

The Bartleet display case advertises shark hooks amid the range of tackle for sale on Christensen’s premises. It worked beyond mere advertising or promotion by associating him and his business with one of the finest hook manufacturers in the world, with representations of the company’s gold-medal awards incorporated into the display. The piece, and its context, are worth exploring in more detail.

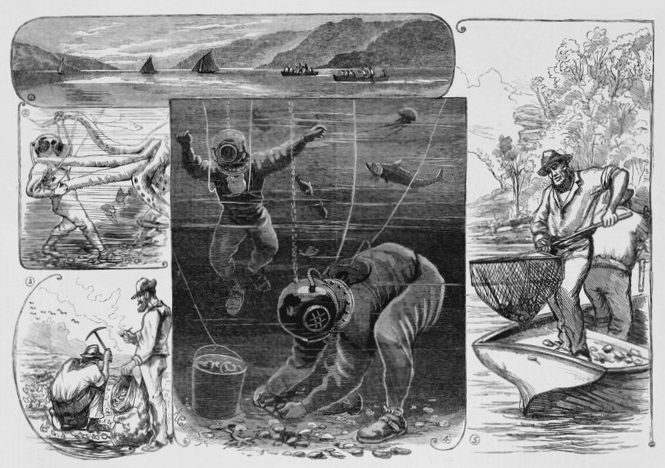

'Scenes from the Sydney Fish Market', published in Australian Town and Country Journal, 15 September 1883

An impressive feat of craft and design, the case is more than a metre square. Encircling its centre are hooks, harpoons and lances – those lethal instruments of the shark hunt to be wrestled into action with the muscle of a leather palm guard. In contrast, the finest of hooks and most delicate of fishing flies crown the display; metal minutiae for the sensitive, skilful hands of the recreational river fisher, a pastime that was growing in popularity with the introduction of salmon and trout to the colonies from the 1860s. Heavy hook chains are similarly juxtaposed with lightweight silk and hemp line. Each group of hooks, lines and flies is identified.

The work was almost certainly produced for display in the Jubilee International Exhibition in Adelaide in 1887 and the Centennial International Exhibition in Melbourne in 1888.5 The extent of Bartleet & Sons’ use of such display cases for promotional and commercial purposes beyond this is not known. Did the company produce variations for businesses such as Christensen’s, or was this, as assumed, a unique item that Christensen procured from the Melbourne exhibition? The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences was given a similar fishing display from Bartleet’s in 1884, while Museum Victoria holds a gothic-inspired needle display that was exhibited at the 1888 Melbourne exhibition.

The Maritime Museum's display comprises sought-after items of fishing tackle that match the description of those from Bartleet's comprehensive entry in the Centennial International Exhibition published in the Argus in October 1888:6

Of fishhooks no less than 1,253 different sorts are exhibited, among which are specimens of the turn-down-eyed hooks made solely by the firm under the instructions of Mr Cholmondeley Pennel, the author of many standard works on fishing and now greatly used by anglers at home. Some Mayfly hooks are also to be seen here … and a variety of other hooks from the tiniest trout hook to an implement big enough to kill a tunny fish or a shark.

In the same case is included a very complete collection of tackle and other appliances for fishing every kind of waters. Among these may be noticed the ‘Archer’ spinner, made in three sizes for pike, salmon, and trout, and capable of being used with almost every kind of natural bait, while for sea fishing the spinner is mounted with brass swivels and japanned trebles. Besides this there are other kinds of spinning bait, such as ‘angel’ and ‘phantom’ minnows and spoons, artificial grasshoppers, caterpillars, bees, wasps, beetles, and every kind of lure for the most dainty or crafty of fishes.

This photo is thought to show Frederick Christensen (centre) in front of his rooms at 151 George Street, Sydney, in the 1890s. Courtesy Christine Fraser

The needle and fishing tackle market was competitive, and Bartleet & Co entered their work in Australian exhibitions alongside that of their competitors from Redditch: J James & Son, S Allcock & Co, and Henry Milward & Sons (the company that, in the 20th century, was to buy Bartleet’s). All four companies were presented ‘first order of merit’awards.

Integral design features of the piece are eight gold medals, or copies of them, that were presented to the firm in Adelaide and Melbourne. The South Australian Advertiser noted in 1887 that Bartleet & Sons had obtained 11 gold and prize medals for excellence, commencing with the first London Exhibition of 1851. This display case boasts of ‘15 gold & prize medals’ in gold lettering across its timber gable – including the awards from Adelaide and Melbourne, no doubt.

Beyond its aesthetic appeal, the beauties of this display case are its strong provenance and links to the working life of Sydney and the oyster rooms of fishing tackle supplier Frederick Christensen.

Christensen’s business was so successful that by the time he died in 1894, he held properties in Cumberland Street (The Rocks), Randwick and Balmain. After his death his third child, 17-year-old Frederick Jr, carried on the business, but only for a few years. A Nicholas & Co operated the saloon from 1896 until about 1912, when it was converted to a butchery.

This striking display case, a gift to the museum from Frederick Christensen Sr’s great-granddaughter, remains a testament to his enterprise. At its new home it enables us to explore the age of industry, the practice of fishing, and above all the seafood habits of Sydney’s colonial population.

References

1 Sydney Morning Herald, 16 May 1863, page 4.

2 Helen Hunwick, The Food and Drink of Sydney: A history, Rowman & Littlefield 2018, p110.

3 ‘Early morning experiences of Sydney’, Australian Town and Country Journal, 15 September 1883.

4 ‘A day’s sharking at Sydney heads’, The Illustrated Sydney News, 3 April 1890, pages 29–30.

5 W Bartleet & Sons had two exhibits at the Melbourne Centennial International Exhibition of 1888. The first was listed as ‘Needles, sewing-machine needles, needle cases, crotchet hooks, fish hooks, fishing tackle’, and the second ‘Needles and sewing machine needles’ (pages 447 and 466, Centennial International Exhibition, Melbourne 1888-1889, Official Record MV). https://collections.museumvictoria.com.au/items/1332487).

6 Argus, Tuesday 23 October 1888, page 58.

This article originally appeared in Signals magazine (Issue 128).