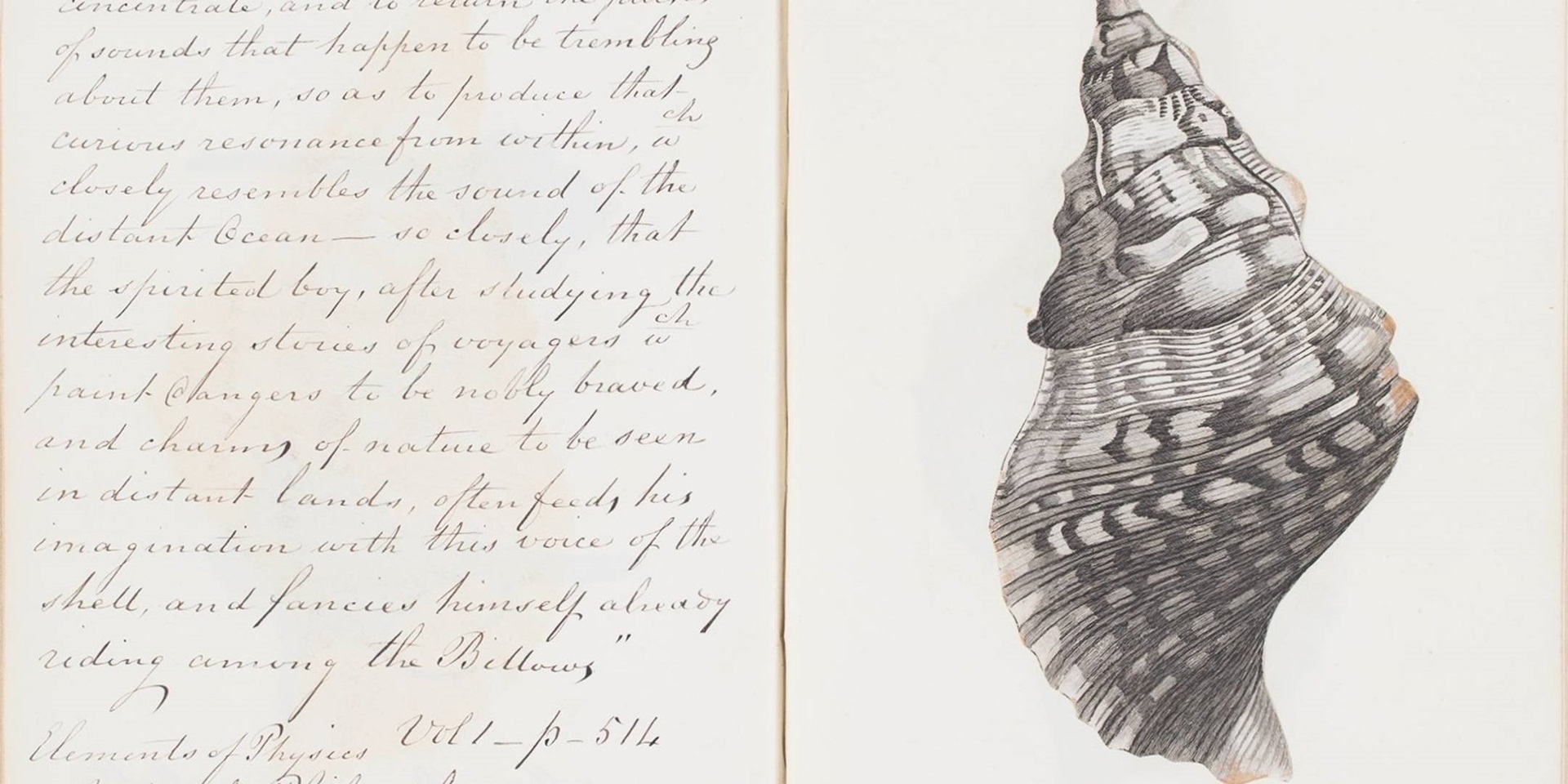

William Bligh is often described as an abusive tyrant, but what about a devoted husband? When William Bligh met Elizabeth Betham, he found his soulmate, and throughout his turbulent life, she remained his great love and ever-constant supporter. As an officer of the Royal Navy, William Bligh was away from his family often, however he bridged the distance by actively collecting shells for his wife. Elizabeth Bligh’s shell collection held scientific and aesthetic interest at the time, but they were also a reflection of love – exotic souvenirs that allowed her to share in her husband’s adventures.

During the 18th century, interest in shell collecting (or conchology), like other areas of the natural sciences, was greatly stimulated by European exploration of the Pacific, particularly due to Captain Cook’s voyages. During Cook’s Endeavour voyage for example, Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander collected shells wherever the ship anchored, returning to England with a large collection.

We don’t know when Elizabeth Bligh started collecting shells, but her father’s position as Collector of Customs at Douglas on the Isle of Man, may have provided early opportunities to acquire shells from the captains and crews of ships passing through the port. What we do know however, is that William Bligh sourced most of the shells in her collection during his voyages to the East Indies, Jamaica, New South Wales and the Pacific.

As master of the Resolution on Cook’s third voyage of exploration, Bligh, like other expeditioners, must have been aware of the money to be made from selling private collections to dealers. The collector Thomas Martyn met the Resolution and Discovery when they returned to England after Cook’s third voyage and purchased two thirds of the shells available for the sum of 400 guineas (equivalent to some $65,000 today). Bligh married Elizabeth in February 1781, some four months after the expedition’s return, and he may have given her shells around that time.

There is little written evidence of William Bligh’s shell collecting. The lack of mention on the Bounty voyage may be due to the disruption caused by the mutiny, but equally because such pursuits were unlikely to warrant noting.

On the second breadfruit expedition, we have a single reference to Bligh’s shell collecting in a letter from Alexander Anderson, the superintendent of the botanical gardens on the West Indian island of St Vincent. Writing to William Forsyth (keeper of the Royal Gardens, Kensington, UK) about Bligh’s arrival aboard the Providence, and delivery of the breadfruit plants to the island, he records: [1]

Captain B bought [no shells] himself, his sole attention being employed on the plants. He even applied to me for shells and other matter for his friends in England.

After her death in 1812, Elizabeth’s entire collection was sold to the dealer John Mawe, who had opened a shop in 1811 in The Strand, London. Mawe was mainly known as a collector of minerals, but he was also interested in shells, publishing The Voyager’s Companion or Shell Collectors Pilot in 1821. Regarded as the world’s first shell collecting guide, the work took the form of a travelogue around the world, noting where rare and valuable shells could be found and how to preserve and pack them. It even included his address, just in case mariners wanted to sell their own shells to Mawe.

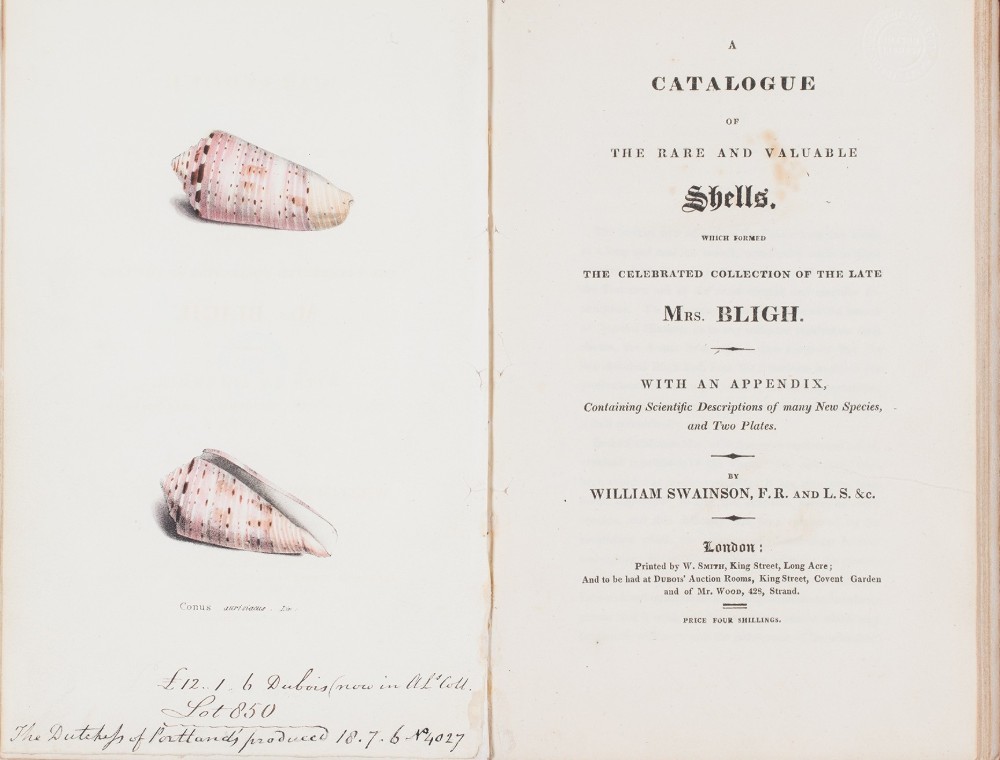

Opening pages from A Catalogue of the rare and valuable shells which formed the celebrated collection of the late Mrs Bligh (1822) by William Swainson. Image courtesy Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, 82/154.

Describing opportunities for shell collecting in Fiji, Mawe stated, ‘The finest volutes ever seen in this country, were collected on Bligh’s Island’. [2] A footnote adds: ‘[Bligh’s] lady possessed one of the finest collections of shells in Europe … This superior and extensive collection passed into my hands for a valuable consideration.’ [3]

In 1822, John Mawe put Elizabeth’s collection of several thousand shells up for auction. Written in the preface to the auction catalogue it was noted: [4]

… To any voyager fond of this beautiful branch of Natural History, or to any collector resident on their shores, the South Seas offer a fine harvest; but the late Admiral Bligh had, from the situations in which his professional eminence placed him, the best opportunities of procuring whatever was most valuable and rare, from a field proverbially rich

Bidders at the auction of Elizabeth’s collections were particularly impressed by lot 1018, the ‘excessively rare, and finely coloured’ [5] Voluta papillosa from the Fiji Islands. This attained the highest price from her collection, selling for £29.18.6 – equivalent to about $5,500 today – to the collector William Broderip.

The auction also included the cabinet that housed Elizabeth Bligh’s shells, which was ‘6 feet wide, 4 feet 6 in height, from the ground, and 2 feet in depth, containing 40 drawers, in 4 divisions, each with a separate folding door, made of mahogany, and the interior lined with Botany Bay wood’. [6] It sold for £30.10 (equivalent to about $5,700 today).

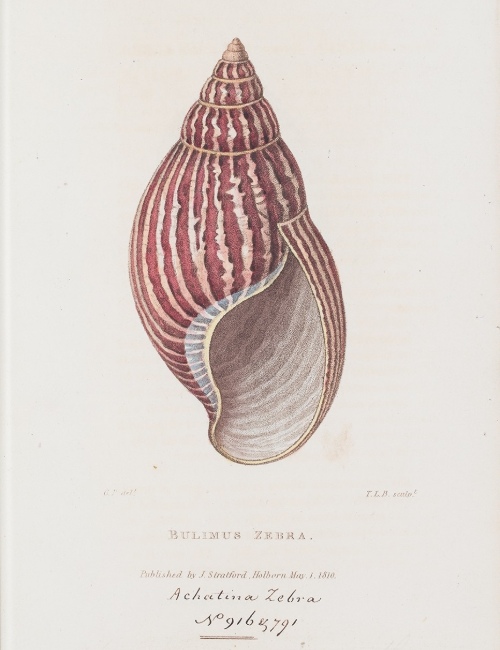

Plate 1, Bulimus Zebra, from A Catalogue of the rare and valuable shells which formed the celebrated collection of the late Mrs Bligh (1822) by William Swainson. Image courtesy Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, 82/154.

What is left of Mrs Bligh’s shells?

Pictures of a few of Elizabeth’s shells were published in Conchology, or the Natural History of Shells by George Perry in 1811, and pictures of a further six shells appeared in William Swainson’s Exotic Conchology a decade later.

William Broderip, the buyer of the Voluta papillosa offered his entire collection to the British Museum in 1836. There it was examined and declared to be ‘one of the most valuable collections … as a consequence of the great attention paid by Mr Broderip to purchase none but the finest that could be procured’. [7]

Later, after the establishment of the Natural History Museum in London, Broderip’s collection was transferred there, and today, an online search of the collection database indicates that a single specimen of Voluta papillosa from his collection survives. Listed as Lot 1018 in the 1822 auction catalogue, Elizabeth’s shell is now the holotype specimen. A holotype, or type specimen, is a valuable original specimen that is either the first known or the only of its kind and is used to describe a new species.

Be sure to visit our current exhibition, Bligh – Hero or Villain where you can view a beautiful array of shells held in the museum’s collection. The Australian shells collected by Mrs Violette Pratten from the 1940s highlight the continuity and appeal of collecting and displaying shells, especially as a hobby for leisured women.

References:

[1] Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, England, archives, FOR/1/4, p 153.

[2] The Voyager’s Companion or Shell Collector’s Pilot, J Mawe, printed and sold by the author, 119 Strand, London, 1821, p 29.

[3] Ibid.

[4] William Swainson, A catalogue of the rare and valuable shells which formed the celebrated collection of the late Mrs. Bligh: with an appendix containing scientific descriptions of many new species and two plates, 1822, p iv.

[5] Ibid, appendix, p 10.

[6] Parliamentary Papers 1837, Vol 40, page 146 (Estimates and Miscellaneous Services; British Museum, Dept of Natural History). An estimate of the sum required to enable the Trustees of the British Museum to purchase the collection of shells belonging to Mr Broderip.