An expedition to Titanic

Last Mysteries of the Titanic was an expedition to the Titanic in June and July of 2005, funded by the Discovery Channel and Earthship Productions, led by filmmaker and explorer James Cameron. The expedition was mounted on board the Russian research vessel Akademik Mystislav Keldysh which departed from St Johns, Newfoundland. The purpose of the expedition was to explore areas deep within the bow section of the wreck using state-of-the-art miniature remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) called 'X-BOTs', and to send the first live video feed from the bottom of the ocean. The investigation did not disturb the sediment layers within Titanic. No artifacts were recovered.

Shirshov Institute of Oceanology research vessel.Image: Brendan Ward..

A legendary ship

RMS Titanic was built at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, Ireland from 1909–1911. It was the most luxurious of three super-liners constructed for the White Star Line (Titanic, Britannic and Olympic).

On the night of April 14, 1912, during its maiden voyage, Titanic struck an iceberg and sank the following morning. Located 323 nautical miles off the coast of Newfoundland, it now rests 3,875 metres beneath the ocean’s surface.

The wreck of Titanic was rediscovered on 1 September 1985, in a joint venture between the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Deep Submergence Laboratory and the Institute Francais de Recherché pour l’Exploitation des Mares (I.F.R.E.M.E.R.).

In 1994, by ‘arresting the wreck’, RMS Titanic, Inc (RMST) gained salvor-in-possession rights. Since then, Titanic has had many visitors with very different motives.

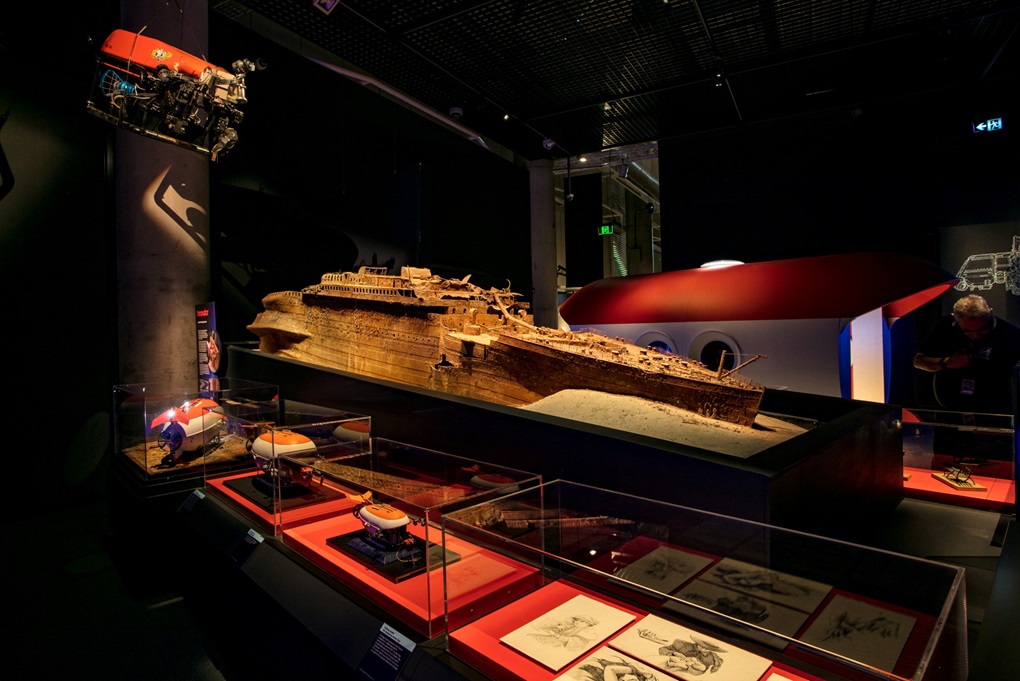

Filming model of the bow section of Titanic, from James Cameron’s personal collection. On display in James Cameron: Challenging the Deep. Photographer Andrew Frolows.

Diving deep

Weighing in at 18.6 tons each, the MIR submersibles were built in Finland in 1987. They are owned and operated by the Shirshov Institute of Oceanology. The MIRs live on board the oceanographic research vessel Keldysh, and are two submersibles rated to dive more than 3,000 metres. The MIRs are battery operated with ballast tanks and a constant atmospheric pressure. When at 3,800 meters (aka the depth of Titanic) where the atmospheric pressure is 400 atm, a Styrofoam cup dangling in a bag on the outside is compressed to 1/8 of its original size… but inside the safety of the sub, you are just fine.

MIR 2 on the deck of Keldysh with two X-BOTs mounted on the exterior in preparation for the dive. Image: Brendan Ward.

One of the X-BOTs developed by Phoenix Engineering for use at extreme depth. The X-BOTs were deployed down the Grand Staircase and were designed for small size and mobility that allowed for ease of exploration and retrieval for confined spaces. Image: Brendan Ward.

Styrofoam cups. Image: Brendan Ward.

Me, the graduate

In 2005, I was a graduate student in maritime archaeology. A friend of mine ran a website called ‘underwater archaeology jobs’ that was (and remains) the one of the best resources for maritime archaeologists looking for fieldwork, funding or career opportunities. He posted a notice about the Last Mysteries of the Titanic project, I made a video, applied and was accepted.

Emily Jateff, aboard Akademik Mystislav Keldysh.

The other maritime archaeologist was Michael Arbuthnot (who later went on to feature on the programs Secret Worlds, Found and America Unearthed). Three incredibly knowledgeable Titanic historians (Ken Marschall, Don Lucas, Parks Stephenson) as well as microbiologists Lori Johnston and Roy Cullimore, who were there to study rusticles, rounded out the investigative team supporting James Cameron’s interior exploration of Titanic’s bow section.

As part of the expedition, I made four dives to Titanic in a MIR submersible.

Preparing to visit Titanic.

Descent

Once the hatch is closed and checks complete, the MIRs are slowly deployed over the side of Keldysh by a crane and cable system. There’s a bit of weaving back and forth, but if the seas aren’t too heavy, it’s just like a cradle.

Once they are free and clear of the vessel, a small boat carrying a specialist nicknamed ‘The Cowboy’ is ferried over. He leaps off the small boat onto the top of the MIR and, riding it like a bull, detaches the cable, then jumps free and swims back.

The Cowboy releasing the cable from the MIRs. Image: Brendan Ward.

Communications and systems are checked again, and when the all clear given, the MIR begins its descent.

The descent averages three to four hours, with about two-to-three hours of working time on the bottom of the dive. An ascent also takes two-to-three hours. So a total 9-12 hour turn around. While the MIR measure 7.8 meters on the exterior, inside it is only two meters across, with the capability to hold two passengers and a pilot. With only two metres of shared space for a 12-hour trip and no mobile phones to amuse you, you’d better be sure you’ve got good dive buddies.

With only two metres of shared space for a 12-hour trip and no mobile phones to amuse you, you’d better be sure you’ve got good dive buddies.

Each passenger is stretched out on a fairly comfortable padded bench, while the pilot is seated in a recessed padded chair in the centre.

There are three viewports, one on each side, and a slightly larger one in the centre for the pilot. The passenger viewports are small, because they have to be. The immense pressure of the water at depth means that smaller and thicker glass apertures present a lower risk of pressure collapse.

We were well prepared for the voyage: it was recommended to eat, but not too much, and hydrate (but not too much of that either!). Remember, the toilet system is fairly primitive – just a bag. The three hour descent is spent checking in with the mother ship and the sister MIR via radio, prepping systems for the bottom and talking about the dive. Through the viewports, you see the colour of the ocean change from blue to black as you slowly descend.

In order to look outside, you press your forehead (and nose, if you have a honker like mine) to the glass and look down, or turn slightly sideways and press your cheek to the glass so that you can peer out and up through one eye.

View from the viewport.

The view isn’t immediately mind-blowing. It’s an immense silty bottom with the occasional ghostly fish, crab or crinoid.

We know so little about this landscape and underrate it because it’s something we don’t completely understand (a very human trait, yes?). The deep ocean is slowly yielding its secrets to science and is also incredibly beautiful. Barking about its barren appearance is like an astronaut whining about the lack of trees on the moon or the earth looking too small.

Inside Titanic

The first time I saw Titanic was on the sonar. It looked surreal. After nothing but the sandy seafloor stretching out in front of us, all of a sudden, my tiny viewport was filled with the side of a mammoth vessel. The steel hull, reaching up above, beyond and all around us. I couldn’t crane my neck enough to see and relied on the searching eyes of our cameras to tell me it was the bow section of Titanic.

Central to the bow section is the Grand Staircase, which extended from the Boat Deck down to E Deck, and the Turkish Baths, creating a path for first class passengers to traverse the ship without having to interact with second or third class passengers. Designed by Thomas Andrews, managing director and head of the design department for Harland and Wolff, the Grand Staircase was carved of oak, with balustrades of wrought iron and gilt bronze, topped by a wrought iron and glass dome. At the base of the stairs stood a statue of a bronze cherub holding a lamp.

Filming model of light-bearing cherub from the grand staircase seen in the movie Titanic. On display in James Cameron: Challenging the Deep. Photographer Andrew Frolows.

Today, the Grand Staircase is devoid of dome, stairs or balustrades. An open shaft, it is the best point of entry into Titanic. To access the interior of the bow section, the MIR submersible hovers over the entrance and deploys its ROVs down the shaft. The second MIR submersible operates as support vessel and is positioned so as to backlight any footage captured by the ROVs or externally–mounted cameras.

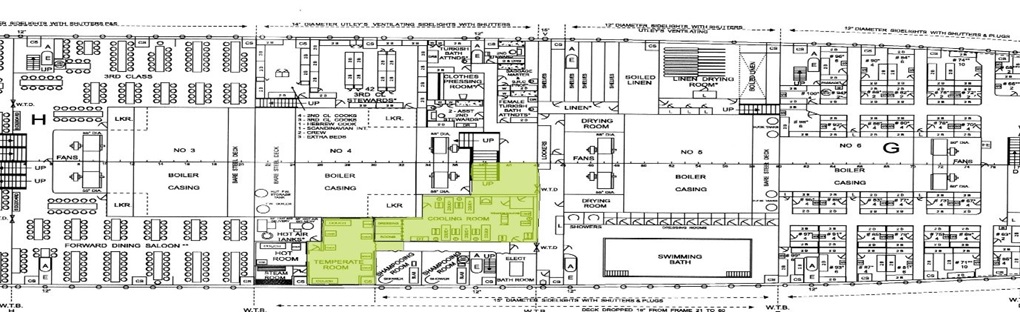

One of the goals of the 2005 expedition was to image the Turkish Baths, located deep within the vessel down on F Deck. Deploying the X-BOTs down the grand staircase, the team manoeuvred them aft of the elevators and into the cooling room, seen in stunning recreated CGI detail here on Park Stephenson’s Marconigraph.

Location of Turkish Baths on F Deck, with areas explored (Cooling Room, Temperate Room) highlighted in green.

Back to the surface

Actual bottom time at these depths is always limited. I wasn’t ever afraid, just excited. And frankly, completely overcome.

It wasn’t until we started our ascent on my first dive that I got a taste of danger. Ghost nets, large fishing nets used by trawlers to indiscriminately scoop up fish from the depths, litter the ocean, even in the deep. During our return to surface, the sub became momentarily entangled in one of these nets and stuck.

I watched the screen as I felt the aft end of the submersible rise, while the nose was still firmly and solidly pointed to the sea floor. 'Just watch the bubbles', said my veteran companion, Mike deGruy, 'if they are still going up, so are we'. Good advice.

An hour or so into the ascent, the adrenalin starts to wear off and you realise that you are hungry. The pilot, Genya, pulled out a small bag and decanted cups of hot strong tea. He broke off pieces of raisin chocolate for us to eat. It’s a bit cold in there and condensation drips down the sides.

At one point, the light for ‘leakage’ came on. I told Genya. 'Is no problem,' he replied. Then the light for "water in sphere" came on. 'Genya,' I said, ‘water in sphere’. 'Is no problem,' he said again, turning it off, with a quick flick of his index finger. I trusted him... and we surfaced just fine.

Resurfacing in the MIRs. Image: Brendan Ward.

Ripples of time

It was an unbelievable adventure and an opportunity for which I will forever be grateful. I was a student, and I looked at the voyage and the vessel with a student’s eye. I thought I wasn’t allowed to be emotional about it. I still thought that science and emotion were two parallel poles that weren’t allowed to cross. I was there to assist with accomplishing a project. But I did get a bit goggle-eyed over the squad of Russian marine engineers who worked all hours to make sure that these exceptional 20-year-old submersibles operated at top capacity at all times. I was overwhelmed by the magic of 200 people crammed together on a ship, the relationships that build and dissolve in moments, yet feel like a lifetime.

We were a big ship, filled with people working at top capacity to achieve a goal. Two miles beneath us, was a ship that only 100 years before, had attempted the same. Beating hearts and furiously crackling synapses heaving together to create a connection between the past and the future.

I think that’s why Titanic is still with us: you have faces, names, stories, objects, you have the ship (and of course, the movie). You have everything you need to create a mythology that withstands the test of time.

James Cameron: Challenging the Deep is on now.