Hidden in the deep

For over 60 years a Japanese midget submarine lay in the waters off Newport, on Sydney’s Northern Beaches. It was one of three submarines to the attack on Sydney Harbour on the evening of 31 May 1942, and the only one whose fate was unknown.

The site was discovered by the ‘No Frills Divers’ group in November 2006, and has been protected by The Heritage Division, Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) since then. As M24 is a war grave and a difficult site to dive, access to the site is restricted.

In 2017 a high resolution 3D model of M24 was produced, providing a map of the wreck in unprecedented detail. This project was a collaboration between OEH and the Australian and New Zealand Chapter of the Explorer’s Club. We spoke to the team leader, maritime archaeologist Matt Carter, about this exciting project.

How do you digitise a submarine?

Photogrammetry. We took thousands of photographs of the site and then fed the images into Agisoft Photoscan, a software program which effectively takes all the information captured in the images and produces an accurate and scalable 3D model. We used GoPros and DSLR cameras to take the photos (and some heavy duty underwater lighting rigs).

Photogrammetry is fast becoming an invaluable site recording technique, especially for land based archaeology sites. But it’s not as common for shipwrecks!

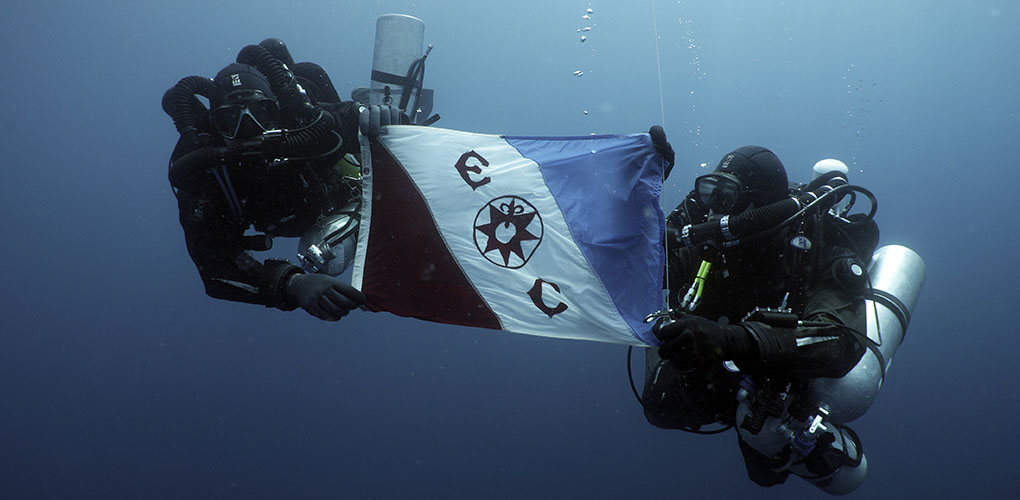

Conducting the photogrammetry survey of M24. Image: Steve Trewavas.

How hard is it to get those photos?

Once we were in the water, visibility was a concern. If you have particles in the water, when you turn on the lights to take the photographs, it’s like trying to photograph a snowstorm. Lot’s of swirling white spots and refracted light. Not what you want for photogrammetry.

M24 is a challenging site, not just the visibility of the water but also the depth of 56 metres. Recreational diving is safe to 30 metres but any deeper than that and you need specialised equipment, training and procedures to dive safely.

We captured a snapshot of the wreck in a particular moment of time. This is the highest resolution map of the site ever produced, the level of detail we now have for the site is light years ahead of what we had before. It means we can more accurately track the degradation and damage over time. We have an amazing baseline for the site - we could go back tomorrow and easily create another model to compare changes to the site.

Animated cut away of M24, created by technical animator Gary Jackson of Headland Creative for a documentary on the Japanese Attack on Sydney. Another example of collaboration between archaeology, science and the arts to explore heritage. Credit: Gary Jackson, ww2australia.com.au.

What does this model mean for making heritage accessible?

There is so much interest in this site, and its story. We can’t all dive on the site. It’s a technical dive. It’s a war grave. It’s protected. But we can make the site accessible virtually. You can see animation and videos of the model online. We’re looking into VR and 3D printing options too.

The project was conducted as the Explorers Club Flag 192 Expedition: Non-Disturbance Archaeological Survey of the M24 Japanese Midget Submarine. Image: Jonathan Di Cecco.

The dive team. From left: Edd Sotckdale, Matt Carter, Jonathon Di Cecco, Karl Graddy, Gideon Liew and Steve Trewavas. Image: Matt Carter (supplied).

The other success of the project was the development of scientific diving protocols to record these sites. Most maritime archaeologists aren’t trained to dive to these depths and OEH has collaborated with Navy divers in the past to get access to the site.

These new protocols are important to allow us to monitor underwater heritage sites deeper than 30 metres. With these protocols, the team can be trained to safely dive to these sites and record them. There are literally dozens and dozens of ship wreck sites around Australia which could be recorded with photogrammetry.

"This is the highest resolution map of the site ever produced,

the level of detail we now have for the site is light years ahead

of what we had before..."

Are you recording any other wrecks?

I'm the research director for The Major Projects Foundation. We're searching for and surveying shipwrecks from World War Two throughout the Asia-Pacific region, which are in danger of polluting the environment.

There hasn’t been a lot of studies of these wrecks or their rate of decay, so we don’t know how or how fast they are corroding. Many wrecks are still leaking oil, which impacts the local ecosystem.

The Foundation’s aim is to locate and model wrecks to bring attention to the problem. This scientific information is needed to make management decisions about the shipwreck: What condition is it in? What was onboard? How much oil was it carrying? How much is left? How long until it ruptures?

We estimate there are 3,300 World War II wrecks in the Pacific. These 3D models allow me to literally show people the wrecks, wrecks they are unlikely to ever dive on or see but still need management plans and for maritime archaeologists, corrosion scientists, marine biologists to work together to monitor these sites. It’s as much an environmental concern as a heritage one.

Cover image: Conducting the photogrammetry survey of M24. Image: Steve Trewavas.