Banks Papers/Series 40.114, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Signatures to a petition to Lieutenant Governor Paterson ‘disapproving of the present measures’, April 1808. Banks Papers/Series 40.114, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

A long history of petitions

When then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull asked his parliamentary colleagues to sign a petition over his leadership in August 2018, the connection may have been lost on many, but petitions have some long historical parallels in the Turnbull family, going back to the so-called ‘Usurpation’ of Governor Bligh in 1808.

Among a list of signatures from Hawkesbury settlers in support of Governor Bligh, who was deposed in the ‘Rum Rebellion’ of January that year, there is one John Turnbull. So dear to his heart was the deposed Bligh that John and his wife began a tradition of giving the middle-name ‘Bligh’ to their children — a tradition that went on through the family including Australia’s 29th Prime Minister Malcolm Bligh Turnbull.

The opening lines of the Hawkesbury address to William Paterson suggest a long lineage of tempestuous moments of Australian political crisis. Banks Papers/Series 40.114, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

Family connections

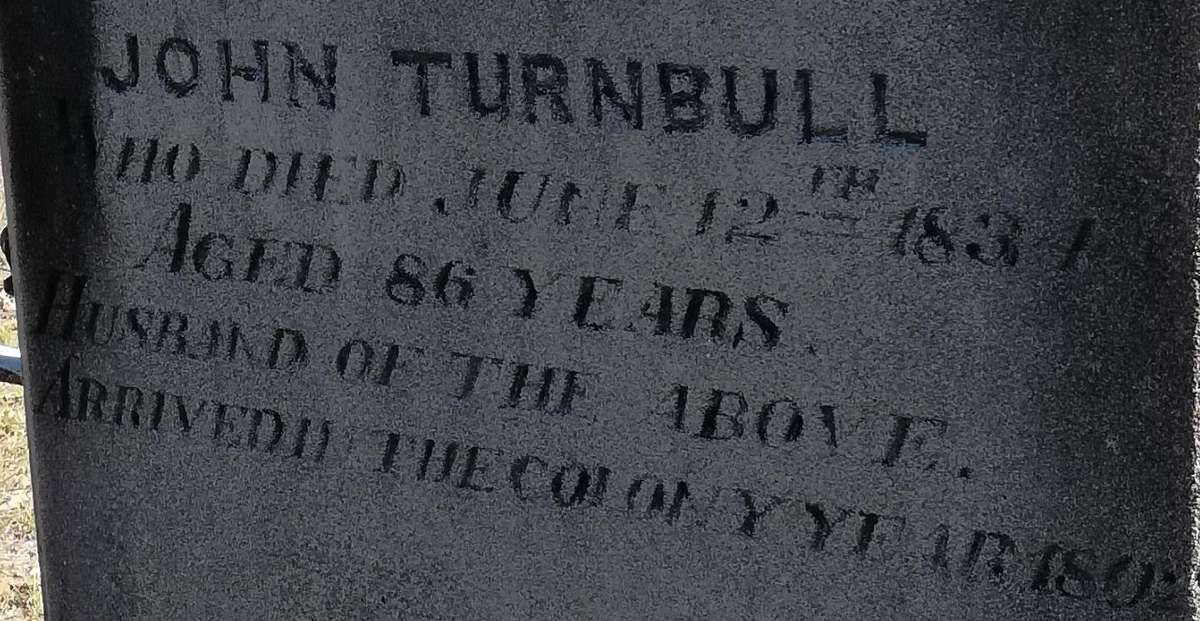

Malcolm Turnbull’s great-great-great grandfather was Scotsman John Turnbull (1751–1834), who arrived on the ship Coromandel in 1802. In an interview in 2015, Malcolm Turnbull said his middle name has been a family tradition for generations, originally given in honour of Governor William Bligh.

Indeed, the Turnbulls weren’t the only Hawkesbury settlers of the early 1800s to show their support for the Governor, who was deposed on January 26 1808, by giving their children the middle name Bligh.

Another headstone at Ebenezer church on the Hawkesbury River, with a Bligh middle name. Image: Dr Nigel Erskine/ANMM.

Support for Bligh

As historian Bruce Baskerville has noted, Bligh’s downfall ‘has been variously described as a coup d’état, a rebellion, an uprising or an insurrection, although the usual description at the time was a usurpation (according to its opponents) or the overthrow of a tyrant (according to its supporters)’.

Despite the political shenanigans of John Macarthur and his supporters (mostly ‘landed interests’ concerned with obtaining more land grants than Bligh felt warranted or useful to the colony) that convinced many in the colony Governor Bligh was indeed a ‘tyrant’ who needed to be deposed, the settlers at the Hawkesbury had fewer qualms with a Governor who had shown them support and established a ‘model farm’ near Windsor.

In fact, soon after arriving in the colony in 1806, Bligh immediately made an impression by providing public assistance to the Hawkesbury settlers who had just survived their fourth devastating flood with great losses to their crops, stock, houses and even lives.

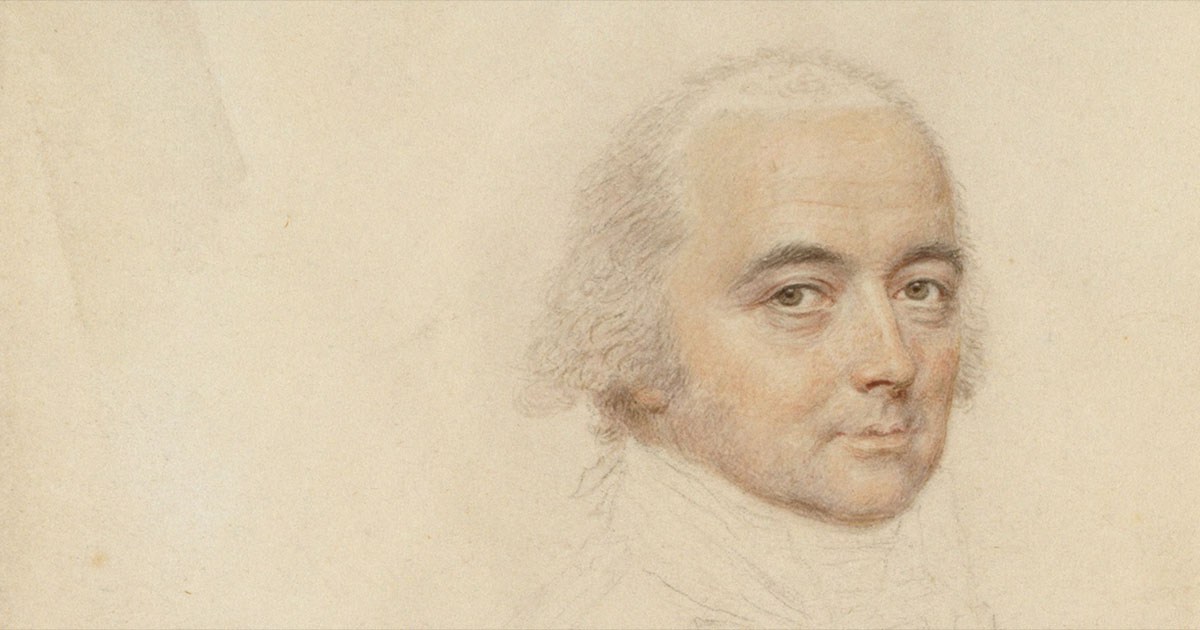

From her 2017 series of miniature portraits Heroes of Colonial Encounters. Repainted, re-Historicised, Helen Tiernan’s ‘Heroes of Colonial Encounters – William Bligh’. As Tiernan notes, ‘the point of post-colonialism is to show how many unresolved issues from colonial history are embedded in the present’. © Helen S Tiernan, ANMM Collection 00055148.

Signing the petition

When the soldiers of the New South Wales Corps, under Major George Johnston marched to Government House and declared martial law, Bligh knew where his support lay. He had hoped he might be able to escape to the Hawkesbury River, where he could rally the settlers and other loyalists.

Yet despite knowing the settlers were ‘in a very enraged state of Mind at the indignity’ Bligh was suffering, he realised their ‘want of Arms’ meant there was little hope against the military.

The Hawkesbury settlers, including John Turnbull, resorted to putting their names to a petition urging the ‘re-establishment of His Majesty’s Government and to restore tranquillity’, though to little avail. The arrival of Governor Macquarie in December 1809 put an end to the upheavals, Bligh returned to England to continue to seek redress and the debate over his role has continued ever since.

The Turnbull headstone at Ebenezer church on the Hawkesbury River. Image: Dr Nigel Erskine/ANMM.

Was Bligh blighted by history?

Governor Bligh suffered the ignominy of being the target of two mutinies and has been a controversial topic for historians. Was he a tyrant? Did he fall foul of many due to his intemperate bad language? With such support from John Turnbull and other Hawkesbury settlers naming their children after him, was Bligh such a bad character after all?

In June 2019 the museum will open a new exhibition: Bligh – Hero or Villain? Curator Dr Nigel Erskine will ask whether the view of Bligh as a villain in the many movies and books about him stands up to close scrutiny. The exhibition will look beyond the stereotypes of Bligh’s other mutiny on HMS Bounty.

Tenacity and determination to overcome all opposition were hallmarks of Bligh’s life, which earned him both praise and loathing, as was seen in the difference between the so-called ‘Loyalists’ of the Hawkesbury settlements and the ‘Usurpers’ of the military and their allied ‘landed interests’ of Macarthur supporters in 1808.

– Dr Stephen Gapps, Curator

Further Reading

- Bruce Baskerville’s blog post ‘‘Ready at all times’: The Hawkesbury resistance to the rum rebels’ is an excellent overview of the topic and historiography.