Unveiling of panels 80 and 81 on the Welcome Wall. From left: Kevin Sumption PSM, Director and CEO of ANMM, Melissa Oujani, Sonia Gandhi, Eva Rossen (Szwarcberg), Dr Ish Sharma and Donna Ingram. Image: Andrew Frolows/ANMM.

Welcome Wall unveiling 23 September 2018

The Welcome Wall pays tribute to the migrants who have travelled the world to call Australia home. More than 200 countries are represented on the Welcome Wall, which faces Darling Harbour and Pyrmont Bay, where many migrants arrived in Australia.

503 names were added to the Welcome Wall during Sunday’s ceremony including families from Albania, Argentina, Austria, Burma, Canada, China, Colombia, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechoslovakia, Egypt, Estonia, Fiji, Finland, France Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lebanon, Lithuania, Macedonia, Malawi, Malaysia, Malta, Mauritius, Morocco, New Zealand, Pakistan, Poland, Rhodesia, Romania, Russia, Singapore, Slovenia, South Africa, Sweden, Syria The Netherlands, The Philippines, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, Uruguay, USA, USSR, Vietnam, Yugoslavia and Zimbabwe. There are now a total of 29 957 names on the Welcome Wall.

It was one of our largest unveiling ceremonies, with over 1200 people in attendance. The ceremony was officiated by Kevin Sumption PSM, Director and CEO of ANMM, with a Welcome to Country from Donna Ingram. Guest speakers included Sonia Gandhi of Multicultural NSW and Welcome Wall family representatives Melissa Oujani, Eva Rossen (Szwarcberg) and Dr Ish Sharma, whose speeches are below.

Eva Rossen (Szwarcberg) at the Welcome Wall. Her parents’ names were inscribed on the Wall to commemorate their journey from Poland to Australia after World War II. Image: Andrew Frolows/ANMM.

Eva Rossen (Szwarcberg)

When I arrived in Sydney, Australia, my name was Chava Ita Szwarcberg. It was May 1949 and I was 14-months-old. My parents had had quite a journey from their former homeland of Poland, through war-torn Europe to Australia. The journey had started on 1st September 1939, when Poland was invaded by Hitler`s German Army. Neither of my parents knew this was the start of their journey.

Mum was 17. Dad was 22. Both were the second youngest of their families, each one from a large family with many siblings. Most of their siblings were married with children. Both went through a series of ghettos and camps, including Auschwitz. This was their lives for five years.

How they survived these horrors is beyond me.

In April 1945, they were liberated by the Americans. My parents were sent to displacement camps in Frankfurt, Germany. They put their names and the names of their family members in all the Red Cross Offices they could. They asked everyone, anyone if there was any news of their siblings, the nieces, nephews, uncles, aunts… But no one knew any news.

Only my mother and her younger sister survived the war. My father was the sole survivor of his family.

Mum and Dad met in the Frankfurt displacement camp. They married on 3rd September 1946. I was born in Frankfurt-au-Main, Germany, in March 1948. We were now a little family and it was time to decide where to live. Neither of my parents wanted to go back to Poland. Back to nothing, no family, no friends. Only very bad memories remained in their former home. It was time to start afresh.

My father had suggested Israel, but my mother said “no more wars”. America and Australia were the places to go: Mum`s sister had married and gone to America, so mum wanted to go to America. But dad had a cousin in Australia. They applied to both countries…and Australia accepted us first.

Still, they drew straws to make their final decision: Australia was drawn three times.

We travelled from Frankfurt to Paris, then onwards to Marseille by train. Two pillows and a feather eiderdown their only possessions as my parents made their way onboard the ship that would take them to Australia, the Luciano Manara.

When we arrived, we stayed with dad’s cousins for six weeks until we found a flat on the top floor at 136 Campbell Parade, Bondi Beach. We stayed there until I was 10-years-old. My brother Max was born nine months after we arrived and my sister, Esther, was born 18 months after that. Mum, dad and I became Australian citizens in November 1955. We were our own little nuclear family of five.

Having three children under 4 was extremely hard and lonely for my mum. She had no mother or sisters to share the good and bad times with, to ask advice, or even to just talk to.

Dad went to work the very next day after we arrived in Australia. He was a barber, so sign language, a little Yiddish, Polish and German, served him well till he mastered English. My dad had a number of barbershops over the years. He was a very jovial and friendly man. He was very popular and his customers followed him where ever his shop was.

Mum went to night school to learn English, patternmaking and was soon an accomplished dressmaker. She made all our clothes – even my wedding dress, the bridesmaids’ dresses and her own ensemble. She soon became an outdoor worker for a fashion house. She was paid by the piece and she worked very long hours, even after we were in bed each night.

She was the serious one, the disciplinarian and the homemaker. I know she was very lonely and sad. I tried my best to make her happy. She didn`t talk of the war or her family very often. It was too painful.

Dad would tell us stories sometimes, but we still didn`t really understand the horrors they went through.

Thank you, Australia for taking us in, letting us live our lives and practice our religion without persecution. We love our country and do not want to live anywhere else.

Melissa Oujani is the granddaughter of Luis and Margarita Munoz, Chilean immigrants who arrived in Australia 30 years ago. Image: Andrew Frolows/ANMM.

Melissa Oujani

I am the granddaughter of Luis and Margarita Munoz, Chilean immigrants that arrived in Australia 30 years ago. The first record of Chileans to arrive in Australia was in 1873. Since then over 25,000 Chileans have arrived in search of new opportunities.

The peak of migration to Australia was between the 1970s-1990s, due to economic and political uncertainty. However, the Pinochet military dictatorship of 1973 was the reason thousands of Chileans had to leave the country. For many families it was a life or death situation, the pleads for help were ignored. The orders of Pinochet resulted in more than 30,000 being killed. Thousands disappeared without a trace. For these reasons, 200,000 Chileans left as political exiles.

On 29 April 1988, my mother’s brother was killed in a protest for being an activist at his high school. In October, my grandparents received a humanitarian refugee invitation to leave the country. They chose Australia.

In less than five days, my grandparents and my mother packed their bags with hopes of peace and freedom. My grandparents were in their 40s and my mother was just 19.

They were about to embark on a 30-plus hour flight flight to the unknown. They arrived to the hot, sticky and vibrant Sydney airport on 28th October 1988, with a Humanitarian Refugee status. From there, they were transported to the Migrant Hostel located in Villawood.They had to start life again, from zero.

My family was determined to change their fate. My grandpa said “this is home now, we have to leave the past aside and move on even stronger.”

Tata – my grandfather – had a few jobs here and there. Aweli – my grandma – sold homemade food in the hostel. Mum only knew basic English but as an avid learner and so naturally, in no time she was running the factory she worked.

30 years later the story has evolved and so has Australia. My background is half Chilean-half Azari. We are celebrating our past, our families, and leaving a gift for future generations so that tomorrow they can proudly look back at the Welcome Wall and say my Tatas, or Nonna, Yiayia, you name all the nations that are here gathered today, who one day left the countries they were born in, to call Australia home.

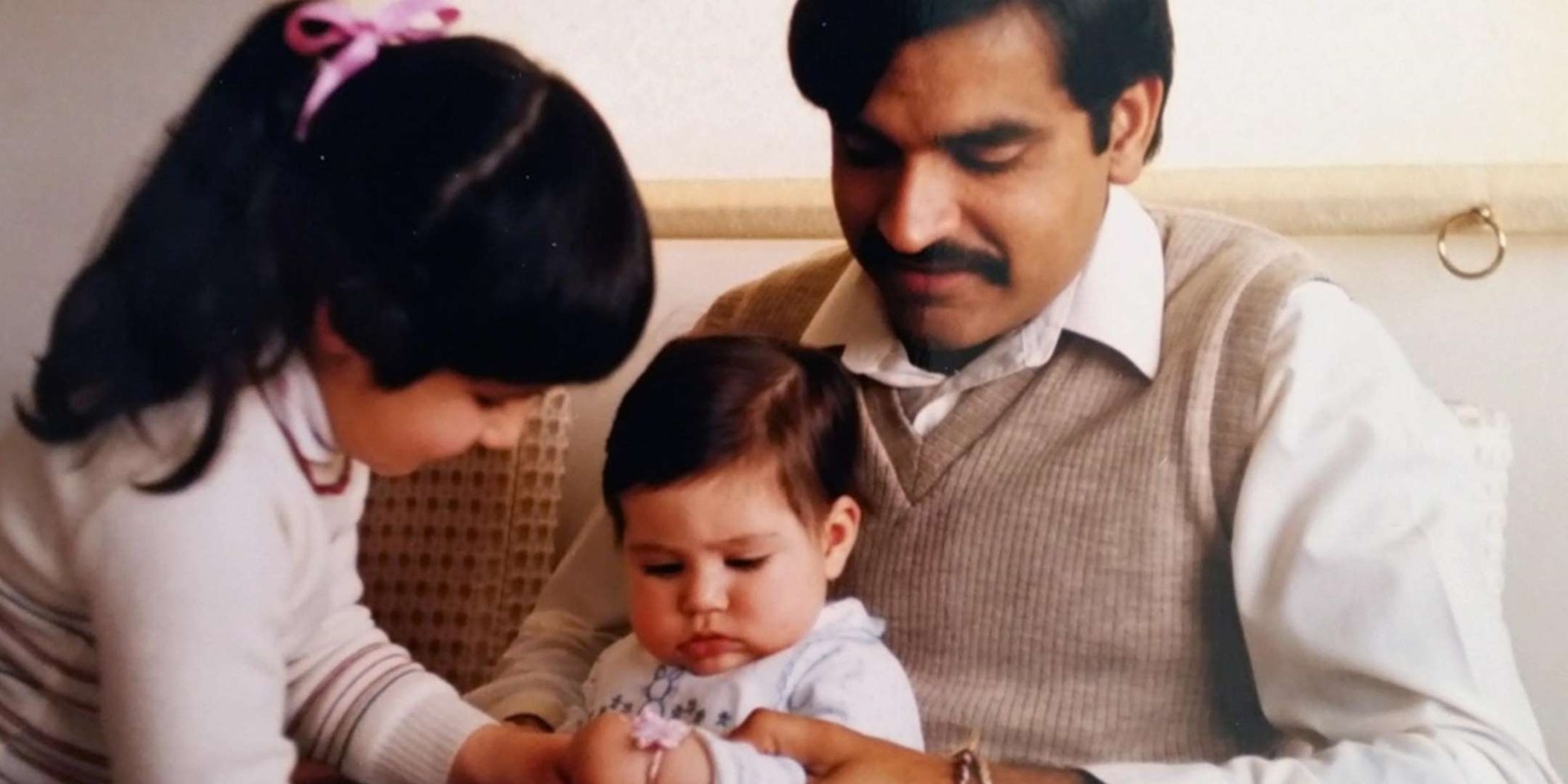

Dr Ish Sharma came to Australia in 1980 to complete a PhD in Science at ANU Canberra. Image: Andrew Frolows/ANMM.

Dr Ish Sharma

I came to Australia in 1980 to do my PhD in Science on a scholarship at ANU Canberra. Those first few months were tough: everything was different educationally, culturally and food wise too. When I first arrived there was another Indian student who had arrived a few months before me by the name of Mr Singh. On the second day in Australia, there was a barbeque for the department and a staff member came to me, welcomed me and quietly mumbled, “How’s things?”

I hesitated as I had never heard this common phrase before, being used to “How do you do?”, “How are you?” etc. The person persisted and asked me again “How’s things?” I thought ‘mmm he must be asking me about Mr Singh, as in “How’s Singh?”’. So I replied, “Oh he’s fine, he’s settling very well!”

At the same barbeque, I tried a sausage for the first time. A lady approached me and said, “Mr Sharma do you know you have just eaten beef?”

I was a bit shocked but then I replied: “well we Indians are not allowed to eat Indian beef, but Australian beef is OK!”

In the department, I found it really awkward to call my supervisor by his first name, and I was given a lot of independence to do my research project which was not what I expected in terms of guidance and support. Culturally, I had to get used to researching and living on my own, making all the decisions. Living in a student residence called Garran HallI, I had to cook, wash and iron for the first time in my life.

It was not until I met my future wife Annette that things started to improve substantially. We married in 1983, when I finished my PhD and I got my first job at the ANBG. We built a house, had two wonderful children, Monica and Jai, and we worked hard in our respective professions.

But how was my life as a migrant different from any normal family building their life in Australia? Well as a migrant I think you need a lot of one particular thing, and that thing is courage.

Courage is often spoken of as something we depend on in an instant, in an unusual moment of danger, to help someone else. But what if we thought about courage as something we need to find in ourselves? What if we need that courage every day for years? Or even decades?

Courage to motivate ourselves when we feel lonely for our homeland, disillusioned or disappointed. It is what gets us through those dark passageways of our own mind, along with a belief in a higher being, reasoned planning, analysis and strength of willpower.

Courage can be inherited – not through DNA, but by example. Children see their parents bravely making their way through a new world with a different language, different values and different cultural traditions. The kids say to themselves “Well, I can take on any challenge too, and do it courageously!” These kids model bravery for their kids and so on for generations.

I am now 61-years-old and I feel no one should be talking about being a migrant without mentioning the fact that Australia is an amazing country. Everything we say about it as a land of opportunity is true. I am extremely grateful to this country for providing everything I needed for a contented life. As a plant scientist, Australia has extraordinarily diverse and unique flora and fauna.

The Welcome Wall is a celebration of the courage of Australia’s migrants and their gratitude for a country that appreciates its migrant population. For all those people who have left the comfortable shores of what is known, loved and understood, who have come to this new land, they are a model for future generations.

Welcome Wall registrations are temporarily on hold. Register your interest here to be the first to hear when registrations re-open. Image: Andrew Frolows/ANMM.

— Edited by Kate Pentecost, Digital Curator and Sabina Peritore, Project Assistant Welcome Wall.