The reality of travelling steerage, where diseases found the perfect conditions. ANMM Collection 00005627

The year 1837 was a busy one for the colony of New South Wales. Busiest of all was Sydney Harbour, which saw thousands of convicts arriving and a growing number of immigrants. In addition to the free single men and women, whole families were travelling from Britain to try their luck with a new life.

On 5 November 1836 the immigrant ship Lady McNaughton left Ireland for Australia. On board was the largest number of children ever to immigrate to Australia at that time. Passenger lists show 196 of the passengers of the ship were under the age of 14. However, by the time the ship was about 300 kilometres from Sydney, 54 of the passengers had died – 44 of those being children. Even in the age of dangerous sea travel, this was an extraordinarily high death rate. The typhus fever on board showed no signs of abating, with some 90 passengers still afflicted.

Sydney Harbour in 1837 – not the best-prepared location for a typhus fever outbreak. View of Sydney Cove and Fort Macquarie by Conrad Martens, courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

But at this stage the ship met HMS Rattlesnake, on its way down to Port Phillip with Governor Bourke aboard. Upon hearing of the terrible state of the Lady McNaughton, it was decided that the Rattlesnake‘s assistant surgeon would go with the Lady McNaughton back to Sydney, as their surgeon had taken ill himself. Bourke sent instructions on the quarantine arrangements to be carried out in Sydney, where the colony was unaware that it was about to face its biggest medical challenge to date.

By the time Rattlesnake and Governor Bourke returned to Sydney on 8 April, the Lady McNaughton had quarantined its surviving passengers at Manly, on the northern entrance to the harbour. A further four adults and 10 children had died. Conditions at the isolated location were basic and life in makeshift tents in 37°C February heat did little to restore the passengers’ health or stamina. Bourke proposed a more suitable and permanent solution, which proved to be timely, as only three months later the colony would be tested again.

The Quarantine Station at Manly in its early years. ANMM Collection 00005538.

When the John Barry limped into Sydney on 13 July 1837, the horrors experienced on board could only have been imagined by those who had managed to survive on the Lady McNaughton. Three adults and 22 children had died. In an attempt to dampen local fear, papers played down the episode:

‘We are happy in being enabled to state, from an authentic source, that the alarming reports current in town relative to a violent and dangerous fever raging on board the John Barry, are very nearly without foundation. A medical board went to the quarantine ground yesterday, where the John Barry is lying, and the Executive Council has been summoned to meet this morning to receive their report, which is of the most favourable description. The following is a correct account of the deaths on board since her departure from Scotland; three adults, two men and one woman, and twenty-two infants, whose deaths are attributed to their mothers living upon salt provisions; one of the infants died since the vessel has been in the harbour.’

Whatever the paper proclaimed, it had been very clear to those on board that it was a fever and sickness that had claimed lives.The Rattlesnake was back in Sydney at that time and it is interesting to think of her moored on the harbour with the John Barry close by, after being released from quarantine. After seeing firsthand the despair aboard the Lady McNaughton just three months before, the crew of the Rattlesnake must have been happy to keep well clear of the John Barry.

Aboard the John Barry when it arrived in Sydney was the Crawford family from Dundee. With eight children, and living in steerage where the fever had raged, the parents had done well to get all of them to Sydney alive. One of their children was six-year-old Barbara Crawford. We can never know if Barbara had noticed the Rattlesnake moored nearby in July 1837, but we can say for sure that in 1849 the sight of that same Royal Navy vessel would cause her to sit down and cry.

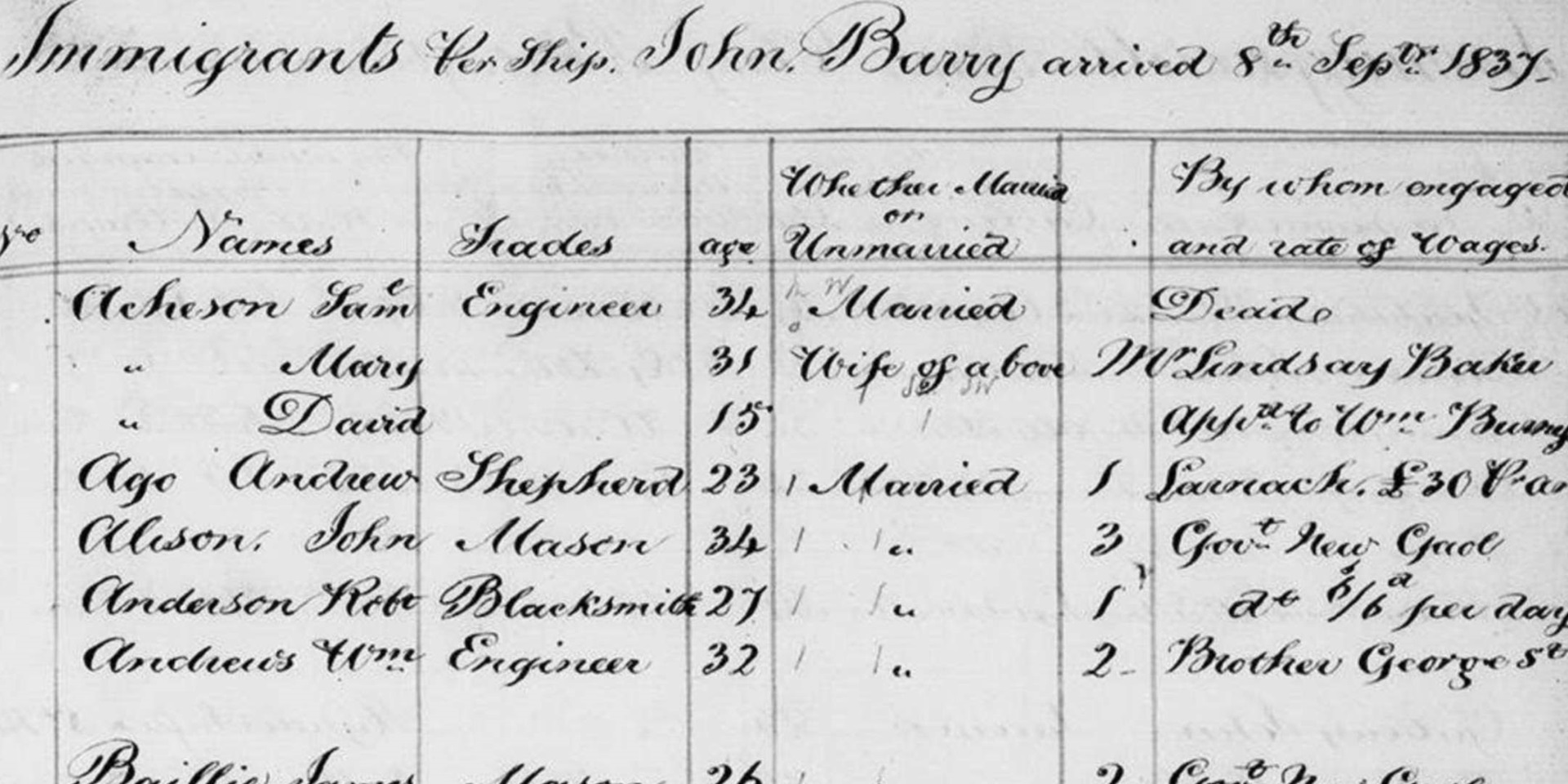

Extract of the passenger list of the John Barry, after it had been released from quarantine. Barbara’s father is listed as Charles Crawford, tinsmith. Although it claims he had seven children, it is understood that another was born on the voyage. Image: NSW State Records.

The Rattlesnake had returned to Australia in 1847 under the command of Captain Owen Stanley. The vessel was undertaking a survey the region of Evans Bay near Cape York in October 1849 when they came across a group of Kaurareg people, among whom was Barbara Crawford. Still less than 20 years old, Barbara had been living with the Kaurareg community for what she thought had been four to five years. She had been rescued by them after her vessel was wrecked and her husband presumed drowned.

Despite living and learning the ways of the Kaurareg, Barbara chose to return to Sydney aboard the Rattlesnake. After being taken aboard Barbara told her story to the artist Oswald Brierly, who was travelling with the survey at the time and had been one of the first to talk to Barbara ashore. Over the long weeks of the journey, Barbara talked to Brierly nearly daily and he wrote down everything she could tell him about her time with the Kaurareg people, drawing and recording what she could tell him of their language, beliefs and way of life. In 1849 this was a significant insight into the traditional way of life of the Indigenous people of the area.

An article about HMS Rattlesnake which briefly related the discovery of Barbara Crawford. Image: Sydney Morning Herald, 20 February 1850, via Trove.

The Rattlesnake moored back in Sydney in February 1850, and after four months aboard, no doubt it was a bittersweet farewell to the ship as Barbara was reunited with her family. After the usual public interest in her experience, little is definitely known about the next stage in Barbara’s life. It is believed she later remarried and died in 1912. No records remain to indicate whether she and Brierly kept in contact, but as Barbara was illiterate, it seems unlikely.

The discovery of Barbara is often overlooked as part of the Rattlesnake’s voyage to Australia in 1847. It became overshadowed by the subsequent death of the captain and the rise to fame of another crew member, the impressive Thomas Huxley. But in hindsight, the survival of Barbara through the trials of the John Barry, a later shipwreck, five years in the extremities of Cape York and her return to Sydney aboard the Rattlesnake is as worthy a story. The contribution of what Brierly recorded from his and Barbara’s conversations is as significant to our understanding of the world as the charts and collections that were made by others.

Want to find out more surprising stories? Why not check out our collection online (Warning: you might lose a few hours doing this).