A watershed for white Australia

When Japanese forces invaded the Netherlands East Indies (NEI, now Indonesia) in 1942, Samuel Jacob (1907–1944) and Annie Maas Jacob O’Keefe (née Dumais) (1908–1974), along with seven of their eight children, were evacuated to safety in Australia. Both Samuel, a headmaster, and Annie, a domestic science teacher, were Dutch subjects by birth and enjoyed many privileges because of their profession. Samuel also served as a civil administrator in the eastern Indonesian city of Merauke, a Dutch military post and site of an Allied air base during the Second World War. While he was decorated for bravery by Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, Samuel’s support of the Allied forces would also put his welfare and that of his family at risk.

Samuel and Annie’s daughter Johanna (Mary) Burns (née Jacob), who was seven years old at the time of her family’s evacuation from the Aru Islands in August 1942, recalls, ‘My father was a head man, a leader, and he was wanted by the Japanese. When the war came, Father and Mother kept things to themselves, and shielded us from complicated things like war. I can remember when the Australian Air Force came and there was a lot of bombing. My parents got us all, packed our things, and we tried to hide to avoid the bombing. Because my father was a wanted man, we owed a lot to his Indonesian followers who helped us to escape from one island to another, from one village to another. And all this happened at night time. We were all separated in the canoes. My eldest brother Samuel [then 13 years old] was left behind because he was at school on another island, Ambon. That was traumatic for my parents, especially for my mother, to leave him behind.’

Samuel, Annie and their seven children – Ann (11), Tineke (nine), Johanna (Mary) (seven), Adolfina (Bernadette) (six), Nicoline (Therese) (four), Adolf (Patrick) (two) and William (John) (one) – were reunited on a yacht in the Arafura Sea and then rescued by the Royal Australian Navy corvette HMAS Warrnambool. They were the only civilian passengers on board. Mary remembers, ‘The Dutch helped transfer us to the warship. They had a call, and the captain said they had to pick up an Indonesian family with some other forces. We were brought to Darwin in September 1942 and settled into a big hospital. The Australian Army was there too.’ The Jacob family was among 15,000 wartime evacuees (nearly 6,000 of whom were non-European) that were granted temporary refuge in Australia on the understanding they would return home at the end of the war.

Following a short stay in Darwin, the family travelled in a military convoy to Adelaide, via Alice Springs. On arrival they were met by the Red Cross and transported to the Metropole Hotel in Bourke Street, Melbourne, where they shared a floor with the NEI Army. Mary states, ‘My parents began looking for a place for the family to live. A lot of the places they went to, they were rejected because a family with seven children was a bit too much for some owners.’ Eventually they rented the ground floor of a two-storey house in Shenfield Avenue, Bonbeach, in Melbourne’s southeast. Their landlord was a retired postal clerk named John William O’Keefe (1889–1975).

In August 1943, Annie gave birth to her ninth child, Peter. She continued working with the Red Cross, while Samuel served as an intelligence operative with the NEI Army in the latter stages of the war. In March 1944, Samuel was sent to New Guinea on a mission for the NEI Intelligence Service, and asked his landlord John O’Keefe to look after his wife and children should anything happen to him. Tragically Samuel died in a plane crash near Mossman, in Far North Queensland, while returning from Merauke in September 1944. Mary says, ‘I don’t even remember my father going away. All I remember is my mother telling us you must write a letter to your papa. My mother got the telegram. My eldest sister Ann was with her. My sister said she cried and cried and cried.’ It was not until 1989 that the wreckage of the Dutch C-47 Dakota was discovered in dense jungle, and Samuel Jacob’s remains were buried in the Cairns War Cemetery.

After the Second World War ended in 1945, the Australian government, under the nation’s first Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell, sought to repatriate all non-European wartime evacuees. While most departed voluntarily, some 800 wanted to stay in Australia permanently. Among them was the widowed Annie and her children, who had now settled into Australian life and were achieving outstanding results at their Chelsea school. In June 1947, in the face of increasing government pressure to leave, Annie and John O’Keefe were married at St Joseph’s Church in Chelsea. Mary recollects, ‘Uncle Jim [as he was known to the children] was a marvellous Irish-Australian. He helped us a lot during our school years with our homework. We’d sit on the big dining table with books everywhere. He helped my elder sister with shorthand. She was a secretary.’ But the government maintained that the marriage did not give Annie the right to remain in Australia as a permanent resident. In early 1949 Calwell issued a deportation order for Annie O’Keefe and her children.

Mary Jacob helps her mother Annie O’Keefe to prepare afternoon tea, 1956. Photographer Neil Murray. Reproduced courtesy National Archives of Australia: A1501, A429/3.

Reflecting on her childhood memories of this period, Mary reveals, ‘We had no idea – we thought we were here permanently. We were kept shielded from all the nasty things as children. My memory as a child was really happy. We had lots of friends and our house was full of kids. When we came to Australia, we lived right on the beach. We used to come home for lunch and go for a swim. The only time we heard what was going on was when the journalists came to our place to interview my mother and some of us. We had no inkling until my mother told us we had to go back. We asked her why but she didn’t tell us why. We were quite amazed really because we’d lived here for a while before this came up.’

"We were kept shielded from all the nasty things as children. My memory as a child was really happy."

Calwell’s controversial deportation order and perceived lack of sympathy for the family attracted widespread criticism in Australia and overseas, and captured the imagination of the media and the public, who rallied behind the O’Keefes. With financial assistance from public donations, the O’Keefe family appealed to the High Court of Australia, mounting what would become the first successful legal challenge to the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (colloquially known as the White Australia policy). This policy aimed to prevent the entry of non-European immigrants through the administration of a dictation test. In March 1949, the High Court ruled that Annie O’Keefe could not be deported because she had not been declared a prohibited immigrant on entry in 1942 (as she had not taken the dictation test), nor could she become a prohibited immigrant through application of the test more than five years after her arrival.

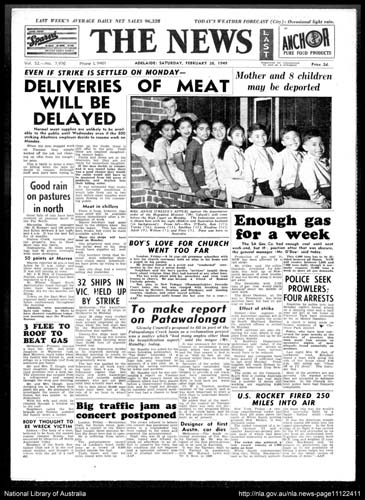

‘Mother and 8 children may be deported’, The News, 26 February 1949, p 1. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

Calwell's controversial deportation order and perceived lack of sympathy for the family attracted widespread criticism in Australia and overseas

Mary recalls, ‘Neighbours and friends had donated money to support our case to pay the court and for our education. The church, the journalists and the papers were very good – they all gathered to organise money. During the case we always had the wireless on. It was to do with the politics in the parliament. And that was the time we used to listen to the politicians talking about immigration. I remember my mother and Uncle Jim coming in and saying we won, we were allowed to stay in Australia.’ The infamous Mrs O’Keefe case helped to pave the way for the gradual dismantling of the White Australia policy throughout the 1950s and 1960s (the policy was finally abolished in 1973). In 1950 Annie and John had a daughter, Geraldine, but sadly Annie’s eldest son Samuel was never permitted to enter Australia. Annie O’Keefe died in Fitzroy in 1974 and John O’Keefe died in Camberwell in 1975.

The O’Keefe family at Bonbeach, Victoria, 1956. Left to right: Annie O’Keefe, Geraldine, John O’Keefe, Peter and Mary. Photographer Neil Murray. Reproduced courtesy National Archives of Australia: A1501, A429/5.

Today the Jacob siblings, many of whom followed their parents into teaching, are dispersed between Australia and Indonesia. Mary, who jokingly refers to herself as ‘the black sheep of the family’, trained as a nurse after completing her secondary education in 1951. She later gained qualifications in midwifery and worked at the Royal Women’s Hospital Melbourne, Chelsea Bush Nursing Hospital and Freemasons Hospital, East Melbourne, until her retirement in 1995. She has been married to architect Peter Burns for more than 50 years and they have two daughters and a son.

Reflecting on her life in Australia, Mary says, ‘I admire all the people that helped my mother, my parents to escape Indonesia. I give credit to them. I admired my mother a lot too. I miss her. There was no beating around the bush with her. I think she died really of stress. She was always worrying – about deportation, the court case, how she could survive, coupon days.’ On behalf of her siblings, Mary registered Samuel Jacob and Annie O’Keefe on the Welcome Wall with the dedication: ‘To our heroes – our parents. Thank you both for your miraculous escape, through the sacrifices of others, during World War II, which enabled us to grow up in this wonderful country Australia.’

This article originally appeared in Signals Magazine (Issue #118).