Recording and re-creating watercraft

Drawing is satisfying. The picture that’s in your mind develops and evolves with the pencil in your hand – sometimes it’s a gradual outline or build-up of elements in a planned fashion, at other times it has more speed as you can sense an area being completed, meeting your expectations or better still providing a surprise as it looks even better than you envisaged. You want to finish it off.

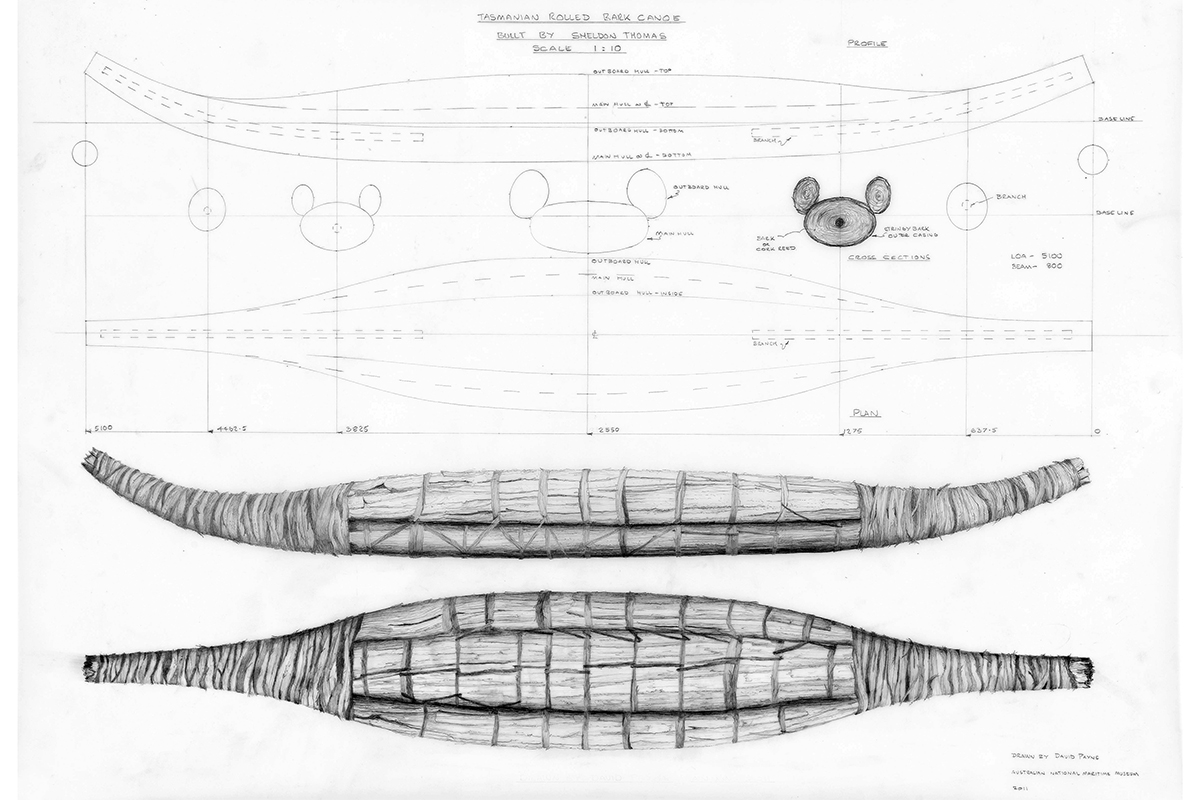

A Tasmanian ningher built by Sheldon Thomas in 2011, now on display at Melaleuca in Tasmania. Image: David Payne.

A Tasmanian ningher built by Sheldon Thomas in 2011, now on display at Melaleuca in Tasmania. Image: David Payne.

With these drawing projects it was both a plan and an illustration coming together, with both parts trying to capture what was unique to each craft. The plan encapsulates an outline of the shape in an orderly fashion, easing out some of the sharp changes in direction and shape. Dimensions give it a comparison in size with others; significant parts are located and their characteristics noted. It’s a record of the facts. And you might use them to make another one, and if you did make another one it would not be identical – that is the beauty of these craft and their building.

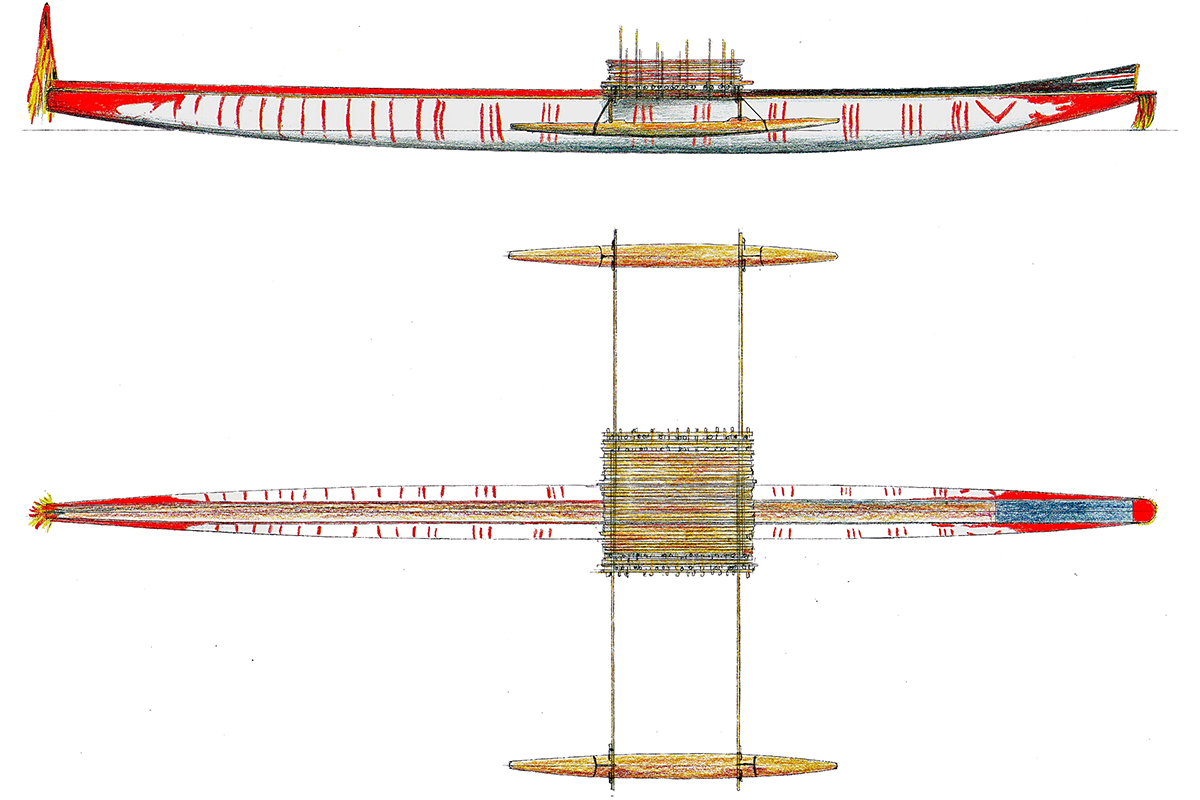

Kai Marrina, a double outrigger from the Torres Strait. This pencil drawing was based on historical documentation from the 1850s. Image: David Payne.

Kai Marrina, a double outrigger from the Torres Strait. This pencil drawing was based on historical documentation from the 1850s. Image: David Payne.

Each one is different, and the shaded illustrations give the picture life and show this craft with all its personal nuances. They highlights the knots, holes, splits, undulations, unevenness, textures and form that make it unique to its builder – their hands made this from the material they chose.

The drawings are in 5H pencil and on drafting film, a modern polyester medium with stability and longevity. A couple of set squares, some curves and the ever-present eraser were the other tools required – but then much of it is freehand too, many hours in total – but you get absorbed in the task and it’s not tedious. It’s actually just as hard to stop and say ‘it’s done’.

The shaded illustrations gives the picture life and show this craft with all its personal nuances.

Model making is enlightening. It teaches you many things in preparation for a bigger project, and produces a lovely artefact. You can experiment, make mistakes and then get it right in a compact, easily managed form. The finished article becomes a prop for presentations – models are easy to show around and generate interest. A number of model-making workshops have been undertaken at the museum, and they have also led to full-size projects. The same materials and same techniques are demonstrated and practised, and the finished model is often ready quite quickly.

Model nawi from a workshop in January 2014. Image: David Payne. Image: David Payne.

Nawi, gumung derrka and ningher models. Image: David Payne.

Nawi, gumung derrka and ningher models. Image: David Payne.

Building is enriching. It is the best way to appreciate everything about the craft. The manual labour gets you as close as possible to the material and the shaping.

Paul Carriage from Ulladulla LALC brings an end together. Image: David Payne.

The projects to make nawi , or tied bark canoes, have used eucalyptus stringybark. This presents as a tough, fibrous material as you lay down the inverted sheet and begin to work it, but as you thin down the material, making the ends much thinner again in preparation for folding, you can feel it developing some pliability. What you have been doing is working with the material, going with the direction of the fibres and the increasing strength of each layer as you go from the rough outside tree surface through to the smooth inner layers. It’s wet with the moisture from its own resin, and with the application of heat over a fire making the bark ends almost too hot to touch, it becomes damp and leathery.

Nawi made at the museum during NAIDOC Week in 2014, currently on display in our EORA gallery. Image: David Payne.

With bare hands it bends, folds, the sides begin to come together and the flat sheet rises up into a canoe shape, a boat made from a completely natural material.