Apartheid, academia and Dutch-Australian connections

Klaas Woldring was born in July 1934 in the university city of Groningen, in the north of the Netherlands. Aafke van Oostrum was born in Utrecht, in the central Netherlands, in October 1936 and was then adopted by a farming family in Munnekezijl, near Groningen. Both Klaas and Aafke were young children when Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands in May 1940, thus marking the beginning of their country’s involvement in the Second World War.

During the Nazi occupation, Klaas’ family spent most of their time in Wassenaar and The Hague, where their house in the Bezuidenhoutkwartier was bombed on 3 March 1945. He remembers the Germans launching long-range V-2 rockets against Allied targets in London, and also the Dutch famine during the winter of 1944–1945 (known as the ‘Hunger Winter’). In the final months of the war, Klaas lived with his grandparents in Groningen, and experienced the onslaught that destroyed half of the city in April 1945. Later that year, after the conflict had ended, he was fortunate to be sent on a children’s health transport to Vejle, Denmark, to recuperate for six months under the care of foster parents. Klaas will never forget travelling through the German cities of Bremen and Hamburg and witnessing the once great centres reduced to rubble as far as the eye could see.

Klaas Woldring (top right) with classmates at Hotelschool The Hague, 1959. Reproduced courtesy Klaas and Aafke Woldring.

Aafke spent most of the war years at her family’s farm in Munnekezijl, apart from a six-month stay at a sanatorium where she was treated for tuberculosis. Sadly her mother died from the disease in 1943. Aafke has vivid memories of the Nazi soldiers confiscating their farm supplies and searching for her father, who often went into hiding to avoid being sent to Germany. Her proudest memory was when the Canadians liberated Groningen in April 1945 and her father was the only person in the whole village who could speak English.

Klaas will never forget travelling through the once-great German cities of Bremen and Hamburg and seeing them reduced to rubble.

Klaas and Aafke met in July 1953, on Klaas’ 19th birthday, and were married in October 1959. In the same year, Klaas completed a diploma in hotel management in The Hague, while Aafke trained in Amsterdam as a registered nurse. She later gained her qualifications in midwifery in Scheveningen, the beachside suburb of The Hague. Shortly after their marriage, in the face of some difficult family circumstances, Klaas and Aafke decided to leave the Netherlands. They considered several options including Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States, but eventually settled on South Africa because of its interesting history and diverse cultural heritage.

Klaas and Aafke Woldring on their wedding day, the Netherlands, 1959. Reproduced courtesy Klaas and Aafke Woldring.

Aafke Woldring on her wedding day, 1959. Reproduced courtesy Klaas and Aafke Woldring.

There had been a Dutch presence at the Cape of Good Hope since the 17th century. In 1652 the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC) established a victualling station at Table Bay to supply fresh meat, fruit and vegetables for ships sailing from the Netherlands to the East Indies (now Indonesia). The Dutch-speaking settlers at this station, which became Cape Town, were the forebears of the Afrikaner communities in South Africa.

Klaas and Aafke spent two and a half years in South Africa, during which time they had two children, Hans (born in Durban in 1959) and Eke (born in Cape Town in 1962). This period had a powerful and enduring effect on their lives. Klaas and Aafke were strongly opposed to apartheid, the system of racial segregation introduced by the governing National Party in 1948, and they were involved in campaigning against the policy for many years.

In 1962 Klaas secured a job as an assistant manager at the new Ridgeway Hotel in Lusaka, capital of the mineral-rich former British protectorate of Northern Rhodesia (which would become the independent Republic of Zambia in October 1964, under the leadership of Kenneth Kaunda). Although it was a time of uncertainty, particularly for the British colonial public servants, the local Zambian population was optimistic about their future. Klaas remembers playing soccer in the country’s new first division league, which included matches with former England international Jackie Sewell, who had been engaged by the City of Lusaka Football Club as a coach and marquee player.

The family immediately felt at home in Sydney and was relieved to discover that Australians rarely discussed politics or race...

In 1963 the young family moved north to jointly manage the new Sea’s Head Hotel in the lead and zinc mining town of Broken Hill (now Kabwe), which was named after a similar mine in far western New South Wales. A year later Klaas and Aafke were invited to take a five-year lease on the hotel, but declined as they felt it was too great a financial risk. In 1964 the couple met some Australian auditors from the Broken Hill mine, who were guests at their hotel. The auditors told them about Australia’s successful mass migration program, and how the Dutch were held in high regard. With their encouragement, the family submitted an application to the Australian High Commission in Pretoria, South Africa, underwent a medical examination, and completed the formalities for their third migration.

In May 1964 the family joined a long list of passengers in Durban awaiting the sea passage to Sydney. It was only on the morning of their departure that they were able to confirm a cabin for Aafke, Hans and Eke on the Shaw Savill liner Northern Star. A few days later, Klaas boarded a flight from Johannesburg to Sydney, where he found casual work in the banquet department of the Chevron-Hilton Hotel in Potts Point. The voyage for Aafke and the children took nine days from Durban to Perth, and three days from Perth to Sydney. On the ship, Aafke met Englishwoman Patricia Wilce, who was also travelling with two children. Aafke’s and Patricia’s husbands met them on arrival in Sydney and the two couples remain friends today.

During their first six rainy weeks in Australia, the Woldring family stayed at a holiday apartment in Albert Gardens, Manly. They later paid a deposit on a two-bedroom flat in the beachside suburb of Coogee, where they lived until 1970. The family immediately felt at home in Sydney and were relieved to discover that people rarely discussed politics or race. However they noticed that Australians had little awareness of the situation in South Africa, until the cancelled cricket tour of 1971 opened up the public debate on apartheid. Australia went on to play an important role in the dismantling of the policy, through the universities, trade unions and the political intervention of leaders such as Malcolm Fraser and Bob Hawke.

Prompted by his experiences of apartheid, Klaas embarked wholeheartedly on the study of government, race relations and political economy. In 1968 he gained a Bachelor of Arts (through part-time study via distance education) from the University of South Africa, while also employed full-time at the reception desk of the Chevron-Hilton. Klaas went on to complete a Master of Arts in Political Science (Comparative Federalism) at the University of Sydney in 1969, followed by a PhD on the international relations of Southern Central and Eastern Africa at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in 1974. He also tutored in political science at UNSW from 1970–1975. At the same time, Aafke obtained further qualifications in nursing and worked as a sister at a baby health clinic. She gave birth to two more children in Sydney, Karin (born 1969) and Oliver (born 1971). The Woldring family became naturalised Australian citizens in 1969.

In 1975, the family of six relocated to Lismore in northeastern NSW, after Klaas was appointed as a lecturer in political and administrative studies at the Northern Rivers College of Advanced Education. When the college was upgraded to Southern Cross University, Klaas was promoted to senior lecturer and then associate professor. Aafke continued her work as an early infant sister in the Northern Rivers region.

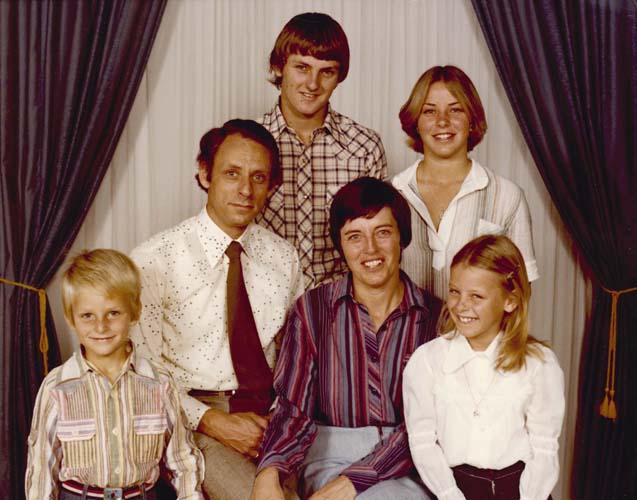

Woldring family portrait in Lismore, NSW, 1978. Reproduced courtesy Klaas and Aafke Woldring.

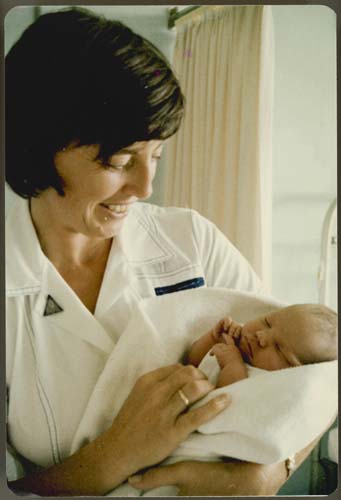

Aafke Woldring at Lismore Base Hospital, NSW, 1984. Reproduced courtesy Klaas and Aafke Woldring.

In the early 1980s, the family returned to Zambia, where Klaas taught for two years as a senior lecturer at the University of Zambia. In the 1990s, he became the head of the School of Management and Marketing at Southern Cross and chair of the Business Faculty Board. He retired in 1999 as an associate professor and took on various part-time teaching appointments at the University of Western Sydney, Macquarie University and Workers’ Educational Association.

One of Klaas’ fondest recollections from his distinguished academic career is the difficulty that many Australian students had with pronouncing or spelling his name. He delighted in commencing each year by showing some 50 different misspellings of his name on an overhead projector, which led the students to contribute further variations. Aafke had the same problem with her name and recalls how some of the new mothers that visited her baby clinic would memorise her name as Agfa. When they forgot, they would call her ‘Kodak’.

Klaas and Aafke, who have nine grandchildren, now live on the Central Coast of NSW. Having encountered very few Dutch immigrants during their time in Lismore, they have become involved with organisations like the Dutch Australian Cultural Centre (DACC), which is based at Holland House in the Sydney suburb of Smithfield. Klaas is currently the secretary of the DACC, having served as president from 2007–2011. As keen supporters of the Dutch community in Australia, Klaas and Aafke registered their names on the Welcome Wall to commemorate their own part in the nation’s migration history following their journey via the Cape.

This article originally appeared in Signals Magazine (Issue #116).