Cathodic Protection System

In 2015, responsibility for preservation, interpretation and exhibition initiatives associated with AE2’s wreck site passed from the AE2 Commemorative Foundation to the Australian National Maritime Museum. Under this mandate, one of ANMM’s primary objectives is to monitor, assess and maintain a cathodic protection system installed on the submarine in 2014 to ensure its continued preservation. The cathodic protection system is a network of three ‘pods’ comprising several sacrificial anodes made of zinc. Each pod weighs approximately 1.5 tons (1,361 kilograms) and was connected to AE2 in order to prevent further corrosion of its hull.

One of the anode pods that comprise the cathodic protection system installed on the AE2 shipwreck site in 2014. Image: Selçuk Kolay/Kolay Marine, Ltd.

When metal surfaces come into contact with electrolytes, they undergo an electrochemical reaction known as corrosion. Corrosion is the process by which a metal returns to its natural state as an ore. The corrosion process causes a metal’s chemical structure to weaken. Iron or steel that is submerged in seawater is one example of a metal coming into contact with an electrolyte. Under normal circumstances, a steel object—such as AE2’s hull—would react with the surrounding seawater and begin to corrode. Over time this would result in its complete disintegration.

Sacrificial anodes are highly active metals that are used to prevent a less active material surface from corroding. They are often created from zinc or magnesium, which has a more negative electrochemical potential than the metal it is used to protect. The anode is connected to the metal it is protecting and consumed in its place, hence the ‘sacrificial’ designation. If given enough time anodes will completely disintegrate and disappear. As a consequence, they must be changed at regular intervals.

Active corrosion of the anodes comprising AE2’s cathodic protection system indicates it is functioning as intended. Image: Selçuk Kolay/Kolay Marine, Ltd.

An inspection of the cathodic protection system was conducted via a remotely-operated vehicle (ROV) in August 2015. The purpose of the inspection was to gather data from monitors attached to the cathodic protection system, review the corrosion rates for each anode pod, and determine whether they were working as designed. An ROV-mounted probe designed to acquire corrosion data from the monitors unfortunately failed; however, the ROV’s cameras acquired video footage and still imagery that showed the anodes were clearly corroding. Further, the level of anode depletion was greater in the submarine’s aft and midships sections, where the concentration of iron and steel internal structural components—such as the engines—is more substantial. This correlates well to the manner in which the cathodic protection system was predicted to operate and indicates it is functioning as intended.

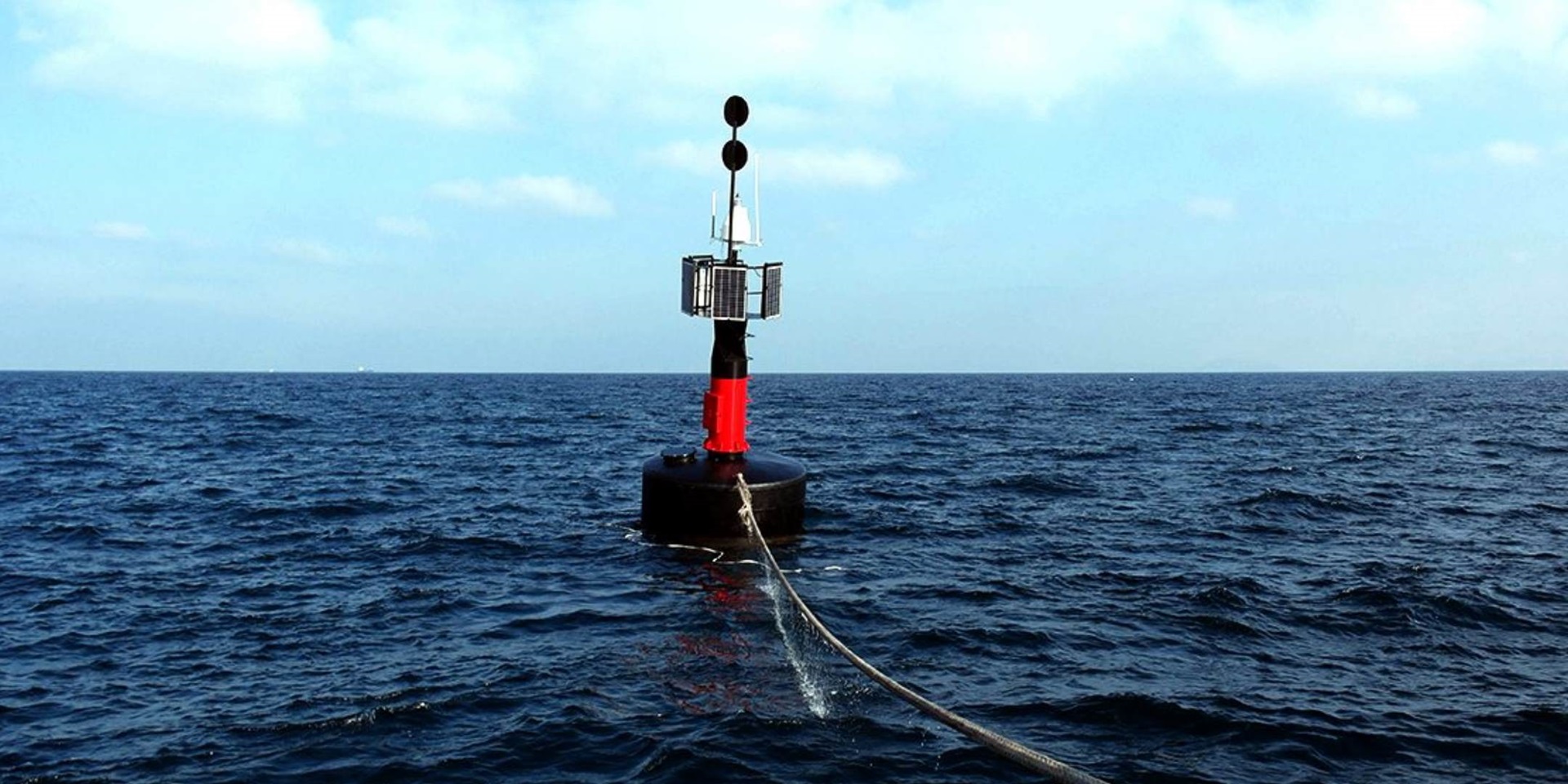

Marker Buoy Replacement

Another task undertaken by the Museum has been to liaise with Turkish government officials and arrange replacement of a large marker buoy moored over AE2’s wreck site in 2014. The buoy was installed as a means to prevent accidental anchor and trawling damage to the submarine’s surviving hull, but was found in April 2015 to have incurred significant damage—including the loss of integrated navigational aids such as its lights and electronic transponder. In addition to being an unmarked hazard to navigation, the buoy’s structural integrity failed, and it began to gradually take on water. Through efforts spearheaded by ANMM Research Associate RADM (Ret.) Peter Briggs, and the Australian Embassy and Office of the Defence Attaché in Ankara, the defective buoy was replaced with a larger, more robust version outfitted with an alarm to prevent unauthorised access to the submarine. In addition, Turkey’s Directorate General of Coastal Safety initiated the process of having the wreck site marked as a ‘protected area’ on official Turkish navigational charts of the Sea of Marmara.

An infographic panel and two zinc anodes (one intact and one depleted) featured in Action Stations illustrate AE2’s cathodic protection system. Image: Andrew Frolows / ANMM.

Exhibition and Interpretive Initiatives

Transfer of responsibility for AE2’s ongoing preservation and interpretation to ANMM coincided with the development of the Museum’s newest exhibition space Action Stations. A sub-section of Action Stations is devoted to maritime archaeology and historic Australian naval shipwrecks, so it was only logical that AE2 should be included as a featured site within the exhibition. The submarine is used as a case-study for identifying shipwreck sites in a touch-screen digital interactive. Using archival photographs and plans, as well as digital images and video of the wreck site, this interactive highlights some of the specific hull features (including the hydroplanes, cutwater bow, and wireless telegraphy mast) that set AE2 apart from other First World War submarine wrecks in Turkish waters.

One of the screens from the AE2 identification digital interactive in Action Stations. Image: ANMM.

The Australian naval shipwrecks digital interactive in Action Stations, showing the AE2 information screen. Image: ANMM.

AE2 also features in another digital interactive that shows the locations of Australian naval shipwrecks around the world. This interactive highlights the historical backgrounds of selected warships, and summarises the results of their respective archaeological studies. In the case of AE2, archival photographs of the submarine are interspersed with digital images and video of the wreck site acquired since its discovery in 1998. Action Stations also includes an infographic panel that discusses in situ preservation of historic shipwrecks, and graphically illustrates the manner in which the cathodic protection system is currently being employed to stabilise AE2’s hull and associated artefacts.

AE2’s forward periscope pedestal as it appeared in 2014. Both of the submarine’s periscopes are fully retracted, which indicates neither were damaged by shellfire from Sultanhisar. Image: AE2 Commemorative Foundation / ANMM.

Moving Forward

Still and video imagery of AE2 acquired during the 2014 archaeological survey has provided a unique opportunity to test historical accounts of the engagement between the submarine and the Ottoman torpedo boat Sultanhisar. For example, Sultanhisar’s commander, Captain Ali Riza, claimed the torpedo boat’s opening salvo struck AE2’s periscope from a distance of approximately 2000 metres; however this is not corroborated by existing accounts of the submarine’s officers and crew. Close examination of site images and footage does not show evident damage to either of AE2’s periscopes, both of which are fully retracted. Indeed, it is highly unlikely that the damaged periscope could have been retracted at all had it been struck directly by shellfire. These findings appear to contradict Riza’s account, and are but one example of a number of contested events during the AE2–Sultanhisar engagement that may be clarified with archaeological evidence.

The anodes that comprise AE2’s cathodic protection system will continue to corrode, and eventually must be replaced before they completely disappear. When installed, the system was projected to operate for approximately ten years, but it is difficult to gauge its actual lifespan without hard data to indicate the rate at which the anodes are depleting. An inspection of the submarine and its cathodic protection system was tentatively scheduled to occur in 2018-2019, but recent events in Turkey may affect those plans and alter the current timetable. In the meantime, AE2 will continue to be preserved where it lay, protected by an army of zinc plates and the deep, dark waters of the Sea of Marmara.

Historic images were sourced from the Australian National Maritime Museum, the Australian War Memorial, the Royal Naval Submarine Museum and the Royal Australian Navy. Still images from inside AE2 are courtesy of Project Silent Anzac, which was funded as part of the Commonwealth’s Anzac Centenary Program 2014-2018. Additional images courtesy Selçuk Kolay/Kolay Marine, Ltd. Navigation Aids Branch/Turkish Directorate General of Coastal Safety and AE2 Commemorative Foundation.