Key inquiry questions:

• What were the motivations for scientists to join HMB Endeavour's voyage of exploration?

• How successful were the scientists in achieving their goals?

Scientific motivations and success

What motivates humans to sail into the unknown? Money, prestige, scientific discoveries, a sense of adventure? Since the early 17th century European explorers have searched the Pacific region looking to extend their economic and political ambitions but for the scientists on board HMB Endeavour it was to expand scientific knowledge in the Age of Reason known as the Enlightenment. Technological innovations that advanced navigation and cartography reduced the risks of earlier seafaring expeditions providing safer passage for wealthy and influential gentlemen.

Charles Green

The Royal Society of London commissioned the Endeavour to solve the mysteries of the universe. The 1769 transit of Venus would answer many of their questions. If the time that it took Venus to cross in front of the Sun could be measured, then the distance between the Sun and the Earth could be calculated, which could give key information to finding out the size of the Universe. Tahiti was identified as a key position to observe this phenomenon that occurs eight years apart then not again for approximately 120 years. Charles Green, an astronomer was appointed by the Royal Society of London to accompany Cook to observe the transit.

On June 3, the day of the transit, Green, Cook and Solander observed and recorded the transit. Cook noted the three observations were different due in part by the black drop effect. Telescopes, diffraction and the sun's atmosphere created a fuzzy outer edge making it difficult to determine the exact times of Venus' transit. This raised doubt on the usefulness of the observations. On their own, HMB Endeavour's results were not conclusive. After HMB Endeavour returned to England all the different results from the different sites around the world were merged creating clearer results. When compared to current measurements, these results were surprisingly accurate. Charles Green died on the return to England suffering from scurvy and dysentery.

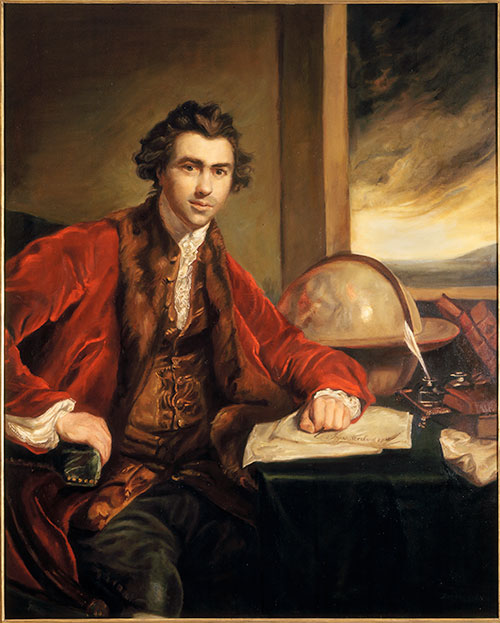

Portrait of Sir Joseph Banks, 1970, by Joyce Aris, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Te Papa 1000-0000-59.

Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander

Joseph Banks was born in London, the son of a wealthy landowner. He was educated at private schools and studied natural history at Oxford University. He was influenced by the lectures and classification method used by Swedish botanist Dr Daniel Solander who became his friend as well as teacher.

At 21, Banks inherited his family estate and become one of England's wealthiest men. He undertook an expedition to Newfoundland and by 1770 was a confidant of King George III and a member of the Royal Society of London.

Banks saw the scientific potential in the expedition to the Pacific and used his contacts and wealth to join. Banks brought with him eight men that included Dr Solander, two artists Sydney Parkinson and Alexander Buchan, four servants trained in collecting specimens and his secretary Herman Spöring.

Banks enthusiastically collected samples of flora and fauna and made thorough and detailed notes in his journal on all aspects of the living world as well as the customs and practices of the indigenous people he encountered. On the return to England Banks and Solander had collected 30,300 plant samples, including 1,400 species previously unknown to Western scientists.

In 1778, Banks was elected president of the Royal Society, a position he held until his death. He supported further scientific expeditions and was fundamental in the decision for the British colonisation of Australia.

What scientific knowledge did Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have in astrology and botany?