Cowra High School - Central West NSW, Australia.

Student researchers at Cowra High School in the rural town of Cowra, Central West NSW, have undertaken this project based on life at the home front during the second world war. The town is well-known for the P.O.W. camp built there in World War II and the breakout of its Japanese prisoners in 1944. The students take us through the events of that time and their effect on the township.

The Cowra P.O.W. camp

Forever Gone, Freedom from Fear

Cowra is a small country town which hides an eventful wartime past within its peaceful landscape. The site of the infamous ‘Cowra Breakout’ has become a centre of healing from its role in WWII. Situated 330 kms south-west of Sydney, Cowra in the 1940s was an average Australian town, with the population of approximately 3,000 people. At the time, Cowra was the site of a major prisoner of war camp which held mostly Japanese and Italian prisoners. Many of the Italians had been captured in the Middle East, while the Japanese had been fighting in and around the Pacific islands directly north of Australia.

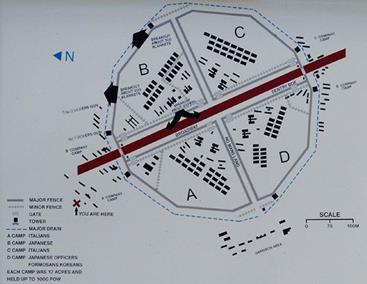

The Cowra P.O.W. camp was huge, covering an area of over thirty hectares, was almost circular in shape and divided into four different compounds. The compounds were separated by two, 700m-long thoroughfares, known respectively as 'No Man’s Land' and 'Broadway', so-called because of its bright lights at night, and was used as an access road for guard vehicles.

Before the Breakout

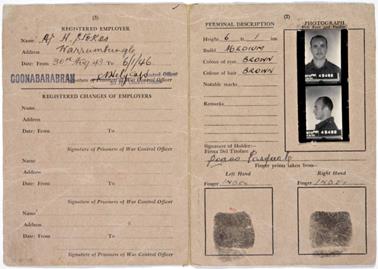

Construction of the P.O.W. camp began in the winter of 1940 and was designed to hold prisoners, mostly Italian, who were brought to Australia from overseas. The camp opened in June 1941, but the first prisoners did not arrive until January 1942. Each compound was surrounded by barbed wire fences, although the first few prisoners lived in tents while their huts were being built. By June 1942, the camp housed almost 500 prisoners; around 350 of those were Japanese. By August 1944, the camp housed almost 1,104 prisoners, 231 of them Italian.

The Italians

The treatment that the Italian P.O.W.’s received during their time at the Cowra camp varied. A former Italian P.O.W. Mick Carmada said that initially the reception they got from the local people was confronting. The Italian prisoners were treated harshly by the local community when they first arrived in Cowra, however as time went on, the Italians became more involved in the community by helping on various projects and eventually became well-liked by the locals. Following the end of the war, several former Italian prisoners chose to remain in Australia and continue their lives in the local community thanks to the largely positive experiences they'd had at the Cowra camp.

The Locals

Cowra locals had positive views of the camp as it brought economic opportunity; on the other hand, it posed a serious security issue, with many worried that their children would be injured during a time of violence. Securing the prisoners provided good money and also fostered a sense of pride in contributing to the war effort, but some people were nervous and uncomfortable with the foreigners being around town. Many people, like the famous Weirs, showed compassion to Japanese soldiers who were found on their property after the breakout by feeding them in their time of need despite the protests of the armed men rounding up the escapees. Acts like this cemented a bond between Cowra and Japan that is still strong today.

The Japanese

While the Italians held in the Cowra P.O.W. camp contributed to the community by working in a wide range of agricultural activities, the Japanese prisoners felt that it was their “duty” to make life for the enemy “as difficult as possible”. While the Italians accepted their capture, some Japanese, who could not be trusted to work outside of the camp, sat and festered with hatred for their Australian guards. Members of the Japanese military had been brought up to believe that any form of capture or surrender was intolerable and brought shame upon not only the individual, but their entire family as well. Because of this belief, the Japanese believed that rather than submit to capture, they should make an attempt to commit suicide or escape.

During the Breakout

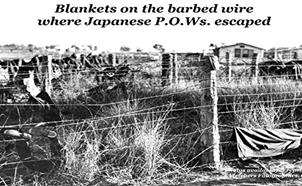

As the winter of 1944 was coming to an end, the Japanese prisoners of the camp joined together in a plot to sabotage their guards and escape the camp. In the early hours of August 5th the prisoners ran to the gates shouting. Guards sounded the alarm with a bugle and fired warning shots. Prisoners began breaking through the wire fences, flinging themselves over using their blankets while armed with makeshift weapons like knives and baseball bats. Within the first few minutes of the breakout attempt guards began firing their machine guns at the first wave of escapees. As the night continued, over 350 prisoners escaped, with many committing suicide, being killed or recaptured.

After the Breakout

Post-war reconciliation began shortly after the war ended and started with the camp being dismantled and the last P.O.W.s being expatriated to their homelands. Over the next 60 years Cowra became a centre of world friendship boasting a positive relationship with the Japanese. This was further strengthened in 1979 when the town's Japanese Gardens were established giving visitors to Cowra a scenic tribute to the ongoing friendship. Other contributions to Cowra included a peace bell, the Japanese war cemetery and the planting of cherry blossom trees. As of today, Cowra has deep cross-cultural goodwill via their international friendship that surprisingly bloomed from tragic origins.