The Seiz family

Departure: Harbin, China, 1955

Arrival: Sydney, Australia, 1955

Vessel: SS Tjibadak

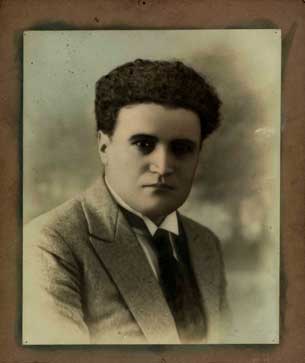

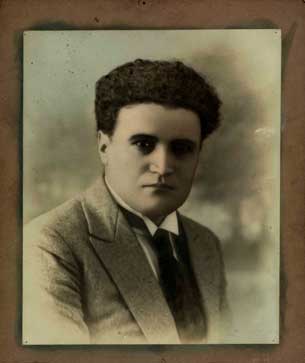

White Russians Ilia Seiz Pocrnja and his wife Katherine fled to China in 1918 after the Bolshevik Revolution. In 1919 Ilia co-founded the English Language School in the northern city of Harbin, home to a vibrant Russian community until the Japanese occupation in the 1930s drove many away. Ilia helped Russians in Harbin to apply for visas for Australia and South America, but was harassed by the police and branded a spy working for Britain and the United States.

Revolution in China

Ilia, Katherine and their adult son Eugene were forced to leave China after the Communist revolution and establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. They packed their precious belongings – Russian vinyl records, photographs, and stamps and language books from the Harbin school – into a Chinese silk-lined trunk, now part of the ANMM collection.

Eugene Seiz remembered, ‘My father said don’t believe [the Communists] son, they have not at all freedom in their country. You can find real free world, only in British countries or US. I believed my father. Our only hope was to get visa to Australia.’

Sponsored to Sydney

In 1955 a Russian family in Sydney sponsored the Seiz family’s migration to Australia on the Royal Interocean liner SS Tjibadak. When they arrived, the word ‘stateless’ was stamped on their immigration papers, even though they had lived in both Russia and China.

Sydney and St Petersburg

In Sydney, Ilia worked as a trimmer at the Dunlopillo factory in Bankstown, Katherine found work in the kitchens at the Imperial Service Club in Barrack Street, and Eugene established the Abode real estate agency. Katherine was an active member of the Russian Catholic congregation in Sydney. She would listen to her classical records as reminders of a distant life in Petrograd (now St Petersburg). Katherine’s granddaughter Natalie says:

She was nostalgic about St Petersburg and living there. Russia was always home … I don’t think she ever really felt she belonged [in Harbin] in the same way that she did in Russia. That was evident in that she didn’t really speak Chinese. I think my father did, but my grandmother seemed to be that stateless person, an outsider, yet within a country. It seemed that when she came here she was still an outsider in Australia. She learnt a bit of the language, enough to get by, but she never became really confident in speaking it.

When Katherine died in 1990, Natalie inherited her possessions from Russia and China, which she treasures as ‘a reminder of my father’s and grandmother’s lives’. The language books, in particular, take on even greater significance as symbols of her grandfather Ilia’s livelihood in Harbin and his desire to resume a teaching career in Australia, her father Eugene’s childhood, and the challenges many migrants face in learning a new language. For Eugene, ‘in Australia is only one difficult thing – language. But if you working on this language – try to speak everywhere in English including home – you will pick it up very quickly. Then everything will be alright.’