![The Observatory, Point Venus, Otahytey [Tahiti], George Tobin, 1792. State Library of New South Wales (FL1606978) The Observatory, Point Venus, Otahytey [Tahiti], George Tobin, 1792. State Library of New South Wales (FL1606978)](/-/media/anmm/images/blog-content/2019/09-sep-2019/signals/the-observatory-point-venus-otahytey-tahiti-george-tobin-1792-state-library-of-new-south-wales-fl160.jpg?h=960&la=en&mw=1920&w=1920)

The museum’s new exhibition Bligh: Hero or Villain? urges us to think about the debates over William Bligh’s personality and career. Curator Dr Stephen Gapps provides some context on an aspect often forgotten among the copious amount of literature, film and discussion around Bligh – the role of the peoples of the Pacific islands in this story.

Have you ever read an account of William Bligh and the mutiny on the Bounty written from the perspective of someone from the Pacific islands? Or seen a film or exhibition on any of the European navigators and voyagers from the point of view of the people whose lives were transformed forever by their arrival? Almost all of our knowledge of Bligh and the story of the Bounty mutiny and subsequent open-boat voyage comes through the work of European and non-Indigenous Australian historians. Yet the experiences of Bligh and other voyagers were deeply tied up in how they were received by the peoples they encountered. Indeed, the routes, the maps and the knowledge gained during all of these 18th-century voyages were in many ways shaped by the Pacific islanders, rather than the other way around.

The Polynesian Triangle is a huge region of Oceania of more than 1,000 islands from Hawai’i in the north to Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the east and Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the south-west. This vast space of ocean, islands and people was where the events of the mutiny, the open-boat voyage and the mutineers’ efforts to establish an island society all unfolded. The origins of Pacific islanders’ responses to Europeans can be seen in events as far back as 1595, when the Spanish navigator Alvaro de Mendana, on a search for the rumoured southern continent of Terra Australis, arrived in the Marquesas Islands. He was met by several hundred canoes and when conflict occurred, more than 200 Marquesans were killed.

The Europeans were often unaware that many major island groups across the Pacific were in regular communication with each other

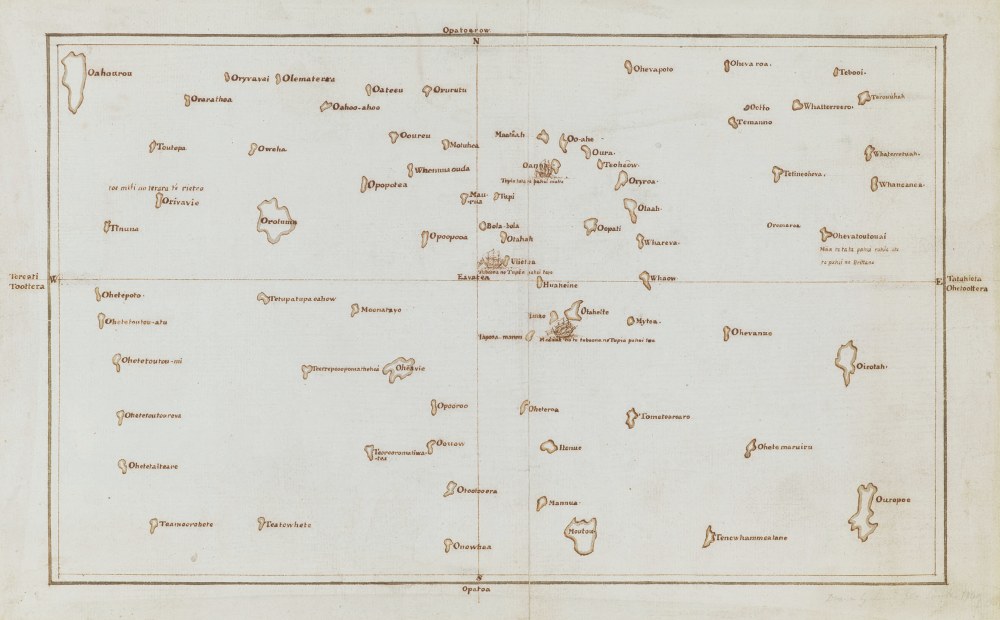

One hundred and seventy-four years after the Spanish violence in the Marquesan islands, Tupaia, a Tahitian priest and navigator with personal knowledge of more than 70 islands in the Pacific, joined the Endeavour voyage, in effect as a pilot. Tupaia recounted the events in the Marquesas to Cook. He drew a map with more than 130 islands on it for Cook, which Joseph Banks described as invaluable information. His map included the Marquesas Islands, and Tupaia described how, in the distant past, four of the islands were visited by ships similar to the British vessels. Cook and Banks took little notice of these oral histories and did not consider that this may have been the violent confrontation of de Mendana and the Marquesans – the Tahitians were, after all, so friendly towards the Endeavour crew in 1769 that it seemed they were not a violent people.

In fact the Tahitians were friendly for a very different reason than Cook’s ideas of their peaceful disposition. When Samuel Wallis had arrived there in the Dolphin in 1767, just two years before Cook, the Ari’i Amo (king) of Tahiti recognised that these voyagers were similar to the white people who had attacked the Marquesans. Around 100 double war canoes loaded with stones attacked the Dolphin for four days until Wallis ordered his crew to fire cannon into the Tahitian fleet and at villages ashore for good measure. The Tahitians rightly regarded this firepower as all but invincible and soon became hospitable. When de Bougainville arrived at Tahiti a year later, he called the Tahitians the friendliest and kindest people in the world, living in a paradise. He did not know that he had Wallis’ cannon fire to thank for his reception.

Captain Samuel Wallis attacked in the Dolphin by Otahitians, artist unknown, c 1800. The painting on this folding screen was copied from an engraving in John Hawkesworth’s 1773 book of Pacific discoveries. ANMM Collection 0006125

As most of us know from the many books and films on the topic, Bligh’s heroic open-boat journey began after the Bounty mutineers cast him and 18 other ‘loyalists’ adrift in the ship’s boat. Bligh hoped to find water and food on the nearby island of Tofua, and then planned to proceed to Tongatapu to seek help in provisioning the boat properly for a voyage to the Dutch East Indies. He had no thoughts of conducting a long open-boat voyage to Timor at that point. At Tofua, however, the initial wary welcome from the islanders turned to fierce resistance. Quartermaster John Norton was killed before the castaways’ boat was pushed out to sea, and Bligh and his remaining men only narrowly escaped a similar fate.

The islanders’ anger was not, as Bligh thought, merely due to the loyalists’ lack of muskets. Instead it seems to have been based on 180-year-old stories of previous visits by the Dutch, handed down over generations on the island. In 1616, Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire had ventured to several Tongan islands. They attempted to hail down a tongaiaki, a Tongan double-outrigger canoe that was voyaging between Tonga and Samoa, curious to see why and how it was so far out to sea. When the islanders ignored their strange commands to stop, the Dutch fired and killed several of them. Later, at Niuatoputapu Island, the Dutch came under attack from a fleet of 23 double canoes and 45 outriggers, incensed at the Dutch attack on the tongaiaki.

Map of some of the Pacific islands known to Tupaia, with Tahiti in the centre, by Captain James Cook, who made his first exploration of the Pacific Ocean between 1769 and 1771. The chart is a copy of an original document by Tupaia. Image © The British Library Board Add.21593 C

Tofua is part of a group of islands in northern Tonga close to where the tongaiaki had been attacked by the Dutch many years earlier. When a group of white sailors landed at Tofua, the memory of the Dutch slaughter of their ancestors was, according to Pacific scholar Jean-Claude Teriierooiterai, foremost in these islanders’ minds. When they attacked and killed John Norton, Bligh – who had just four cutlasses and no muskets – decided to sail for Timor and not to make landfall on any inhabited island for fear of another attack. Bligh’s decision to sail on, undertaking what became the longest open-boat voyage in history, was not a free choice, but was forced on him by the Tofuans. [1]

While there were some friendly encounters that seemed genuine, the islands were in general wary of the arrival of European ships due to their initial violent contact with Dutch and Spanish vessels

The famous French navigator La Perouse visited Samoa in 1787, losing his second-in-command de Langle to an attack by the Tongans. In 1791 HMS Pandora (carrying as prisoners some of the Bounty mutineers) was also attacked by a strong fleet of canoes at Tutuila. And as Bligh himself had experienced first-hand as master of the Resolution on Cook’s third voyage, where he witnessed the death of Cook at the hands of Hawai’ians, Pacific islanders showed no mercy when they perceived the slightest European weakness.

The resistance of Pacific islanders was informed by their communication networks. Even the Bounty mutineers, when in search of a paradise to settle in far from British eyes, were met by an ambush from Tubuai islanders in war canoes loaded with stones. The mutineers fired on them as they sailed into the island’s lagoon, today known as Bloody Bay. Even when the mutineers built a small fort, the islanders resisted their settlement. Fletcher Christian and company ultimately left to search for Pitcairn Island, which they found uninhabited and where they formed their settlement.

![Matavai Bay, Island of Otahytey [Tahiti] Sun set, by George Tobin, 1792. Image State Library of New South Wales FL1606990](/-/media/anmm/images/blog-content/2019/09-sep-2019/signals/hms-providence-1811_1000.jpg?la=en)

Matavai Bay, Island of Otahytey [Tahiti] Sun set, by George Tobin, 1792. Image courtesy State Library of New South Wales FL1606990

The story of the mutiny on the Bounty did not take place on a blank canvas, but across a rich tapestry of thriving cultures that were ultimately forced by firearms to acquiesce to Europeans. The legend of Bligh’s navigation skills is a case in point. Cook and earlier voyagers all marvelled at the Polynesians’ navigation skills that could take them hundreds of miles from the nearest land and back again, precisely into safe harbours. Their knowledge of the night sky, in particular, astounded the Europeans. At a time when Europeans were still trying to solve the difficulties of accurate longitude, the Polynesians had been traversing oceans with pinpoint accuracy for centuries. The European surface grid of longitude and latitude was mirrored by Polynesian sky maps – tracking the route of certain stars and the rhumb lines of others meant Polynesian navigators could sail over horizons and return. European and Polynesian navigation systems are in fact quite similar; both systems ‘define positions on the surface of the Earth using two coordinates that vary at right angles to each other and use stars, and to a lesser extent the sun, to determine directions’. [2] Cook had learned Pacific navigation skills from Tupaia. Indeed, it is possible that William Bligh’s time with Tahitians and his navigation lessons from Cook himself contained some of Tupaia’s vast knowledge of the Pacific. [3]

Most of the narratives of the Bounty tale with which we are so familiar are about the navigational achievements of the British, in particular William Bligh. The amazing, arguably superior navigational skills and knowledge of the Polynesians were all but wiped away from these stories as the Pacific was colonised by Europeans in the wake of Cook and Bligh. Lacking an expert Polynesian navigator on board, the Bounty mutineers were not aware of the many islands on Tupaia’s map that might have been better places for their reclusive settlement. With the revival of traditional boat building and voyaging among Polynesians in recent years, the profound influence of the peoples of the Pacific on the grand narratives of European voyages is slowly unfolding.

References:

[1] Jean-Claude Teriierooiterai, ‘Contextualising the Bounty in Pacific Maritime Culture’ in Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega (ed), The Bounty from the beach, ANU Press, Canberra, 2018, pp 21–65.

[2] M Walker (2012) ‘Navigating oceans and cultures: Polynesian and European navigation systems in the late eighteenth century’, Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 42:2, 93–98.

[3] Ibid. For more information about traditional Polynesian navigation, see Signals 111 (June–August 2015).

This article originally appeared in Signals magazine (Issue 128).