Over the last few months, museum conservators Katie Wood and Lucilla Ronai have had the meticulous task of treating a hand-written letter by William Bligh’s daughter Frances. Currently on display in our exhibition Bligh – Hero or Villain?, I spoke to the pair to find out how they got this special item display ready.

Each object held in the museum's collection is first sent to us (Conservation!) before it is displayed in an exhibition. We determine if the item is stable, in a suitable condition for display, and if any treatment or a special support is required. This ensures that the items are displayed safely and beautifully.

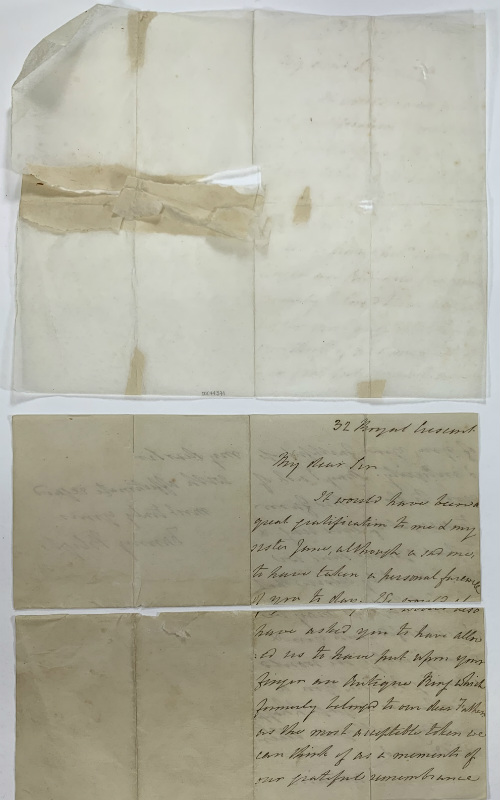

Before being displayed in Bligh – Hero or Villain?, Frances Bligh’s letter was brought to the Conservation Laboratory. Addressed to George Suttor – one of William Bligh’s most prominent supporters during the Rum Rebellion – this letter accompanied a small package that contained:

… an antique ring which formerly belonged to our dear Father, as the most acceptable token we can think of as a memento of our grateful remembrance of you, your faithfulness and integrity.

Condition and Cross-Examination

The condition of an item can tell you so much about its history – how it was used, and whether it was looked after carefully or not. It also reveals the strengths and weaknesses that are important to know for displaying an item. We looked closely at the letter’s condition using different lighting conditions, including:

- Reflected light (how you normally view an item)

- Raking light (angling a torch across the surface of the letter to see its characteristics and texture)

- Transmitted light (shining a light from underneath)

Special photographs were taken of the letter using these three different lighting methods to record the structure of the letter, its material, condition and areas of vulnerability.

The three different lighting methods used to determine the letter's condition

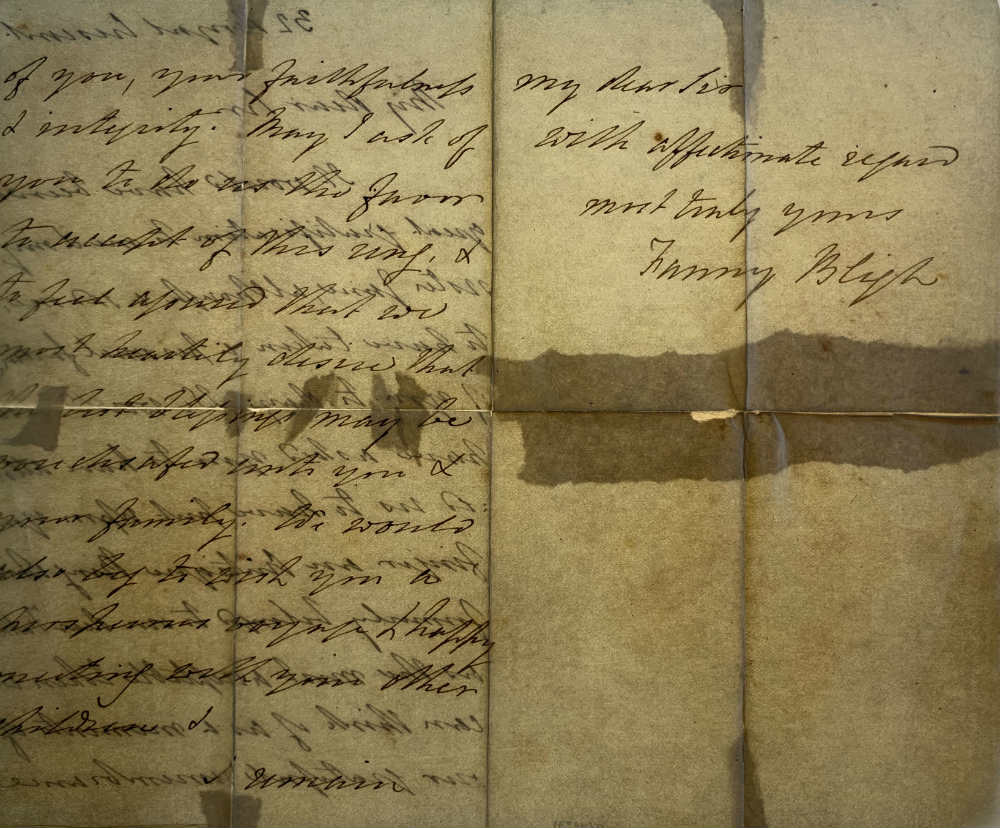

The photographs confirmed what we had suspected – the letter had undergone a cosmetic treatment before the museum acquired the piece. Possibly completed by a conservator at an auction house, the letter had a full-facing repair on the front and back (something we generally avoid). Instead of small repairs to fix different tears, they had covered the whole thing.

The repair was problematic as it was obscuring parts of the text and was unnecessarily large for such small tears. While we do want conservators’ repairs to be detectable, it’s important to make sure they don’t draw away the eye as we don’t want the interpretation of the object to change.

.jpg?la=en)

The haziness in the bottom-right corner is evidence of the full-facing repair that had been completed previously. On the left-hand side, you can see that the repair is also obscuring the text.

Here you can see the large pieces of Japanese tissue paper that were used to repair the various tears, the most obvious being the tear along the horizontal fold line (especially on the right-hand-side).

Testing and Treatment

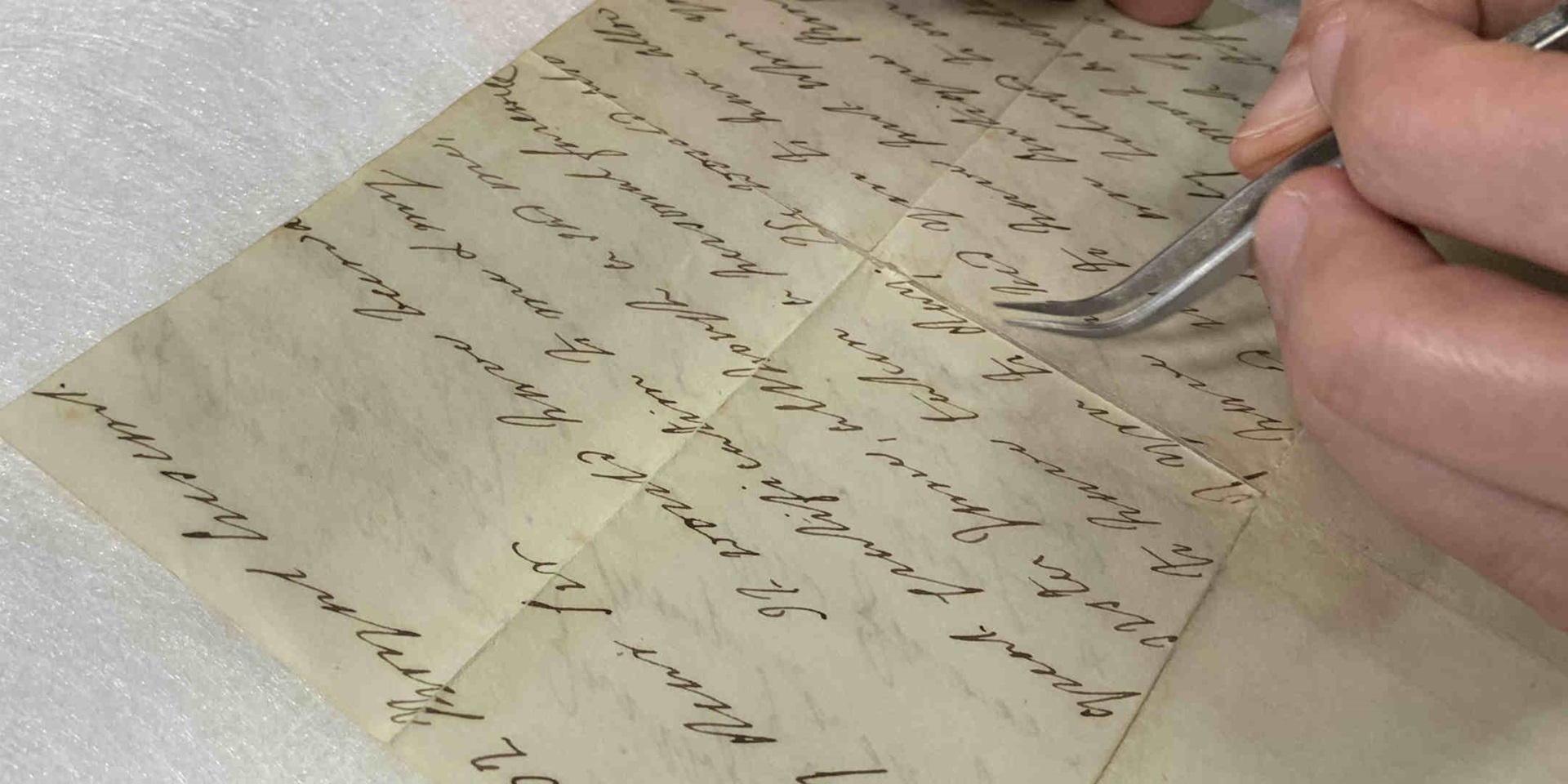

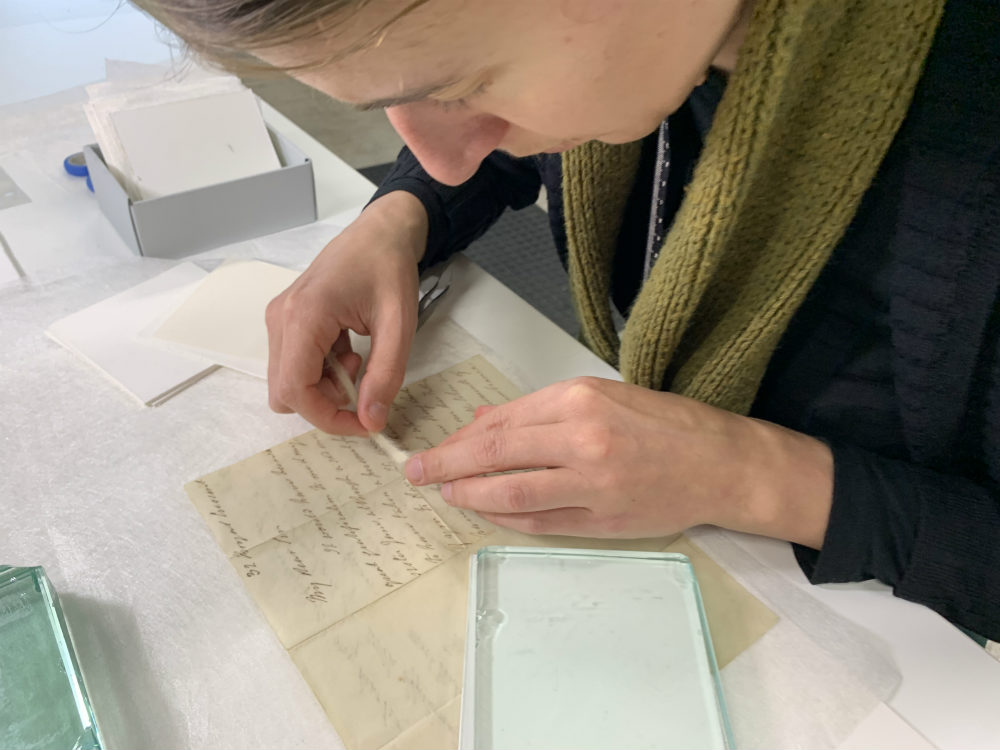

After conducting some small tests, we worked out we could remove the facing repair without damaging the letter. The repair was lifted off with a special stainless steel spatula. Sometimes if the adhesive used to attach the repair to the paper is too strong and you try to peel it off, it will actually peel the layers of the original paper, resulting in severe damage. Thankfully, the old repair came off easily so we didn’t have to worry about this being an issue. You can see it being removed below.

A five-hour process shown in seconds: Conservator Lucilla uses a special stainless steel spatula to remove the old repair

Once the old repair was removed, we discovered the letter was in two separate pieces. Fold lines on paper can become a point of weakness, especially when it is more than 180 years old. In this case, the letter had torn across the horizontal fold line, where it had been folded to fit into the envelope (also part of the museum’s collection). There were also small tears across the vertical fold lines. Now that we had revealed the damage to the letter, we wanted to repair all of it – not only for visual reasons, but also to prevent further damage in the future.

The repair that was lifted from the original letter (seen below in this image)

To repair the tears we used extremely small pieces of Japanese tissue paper that had been specially sized and toned to match the original colour of the letter. Japanese tissue paper is a conservation grade material that is stable, proven to last and will not impact the letter in any way (other than repair it). Using tweezers, we placed the pieces in-between the handwritten letters and used tiny amounts of wheat starch paste to adhere the repairs.

Conservator Katie working out the appropriate size to cut the Japanese tissue paper repairs so they can fit seamlessly in-between the handwritten letters.

While it was a slow and laborious process, the letter is now in a safer condition for display both now and in the future and we couldn’t be happier!

Be sure to visit our current exhibition, Bligh – Hero or Villain? where you can admire the hard work of our conservation team and read this letter that provides insight into Bligh’s illustrious career and his supporters.