The sinking of HMAS Armidale (I)

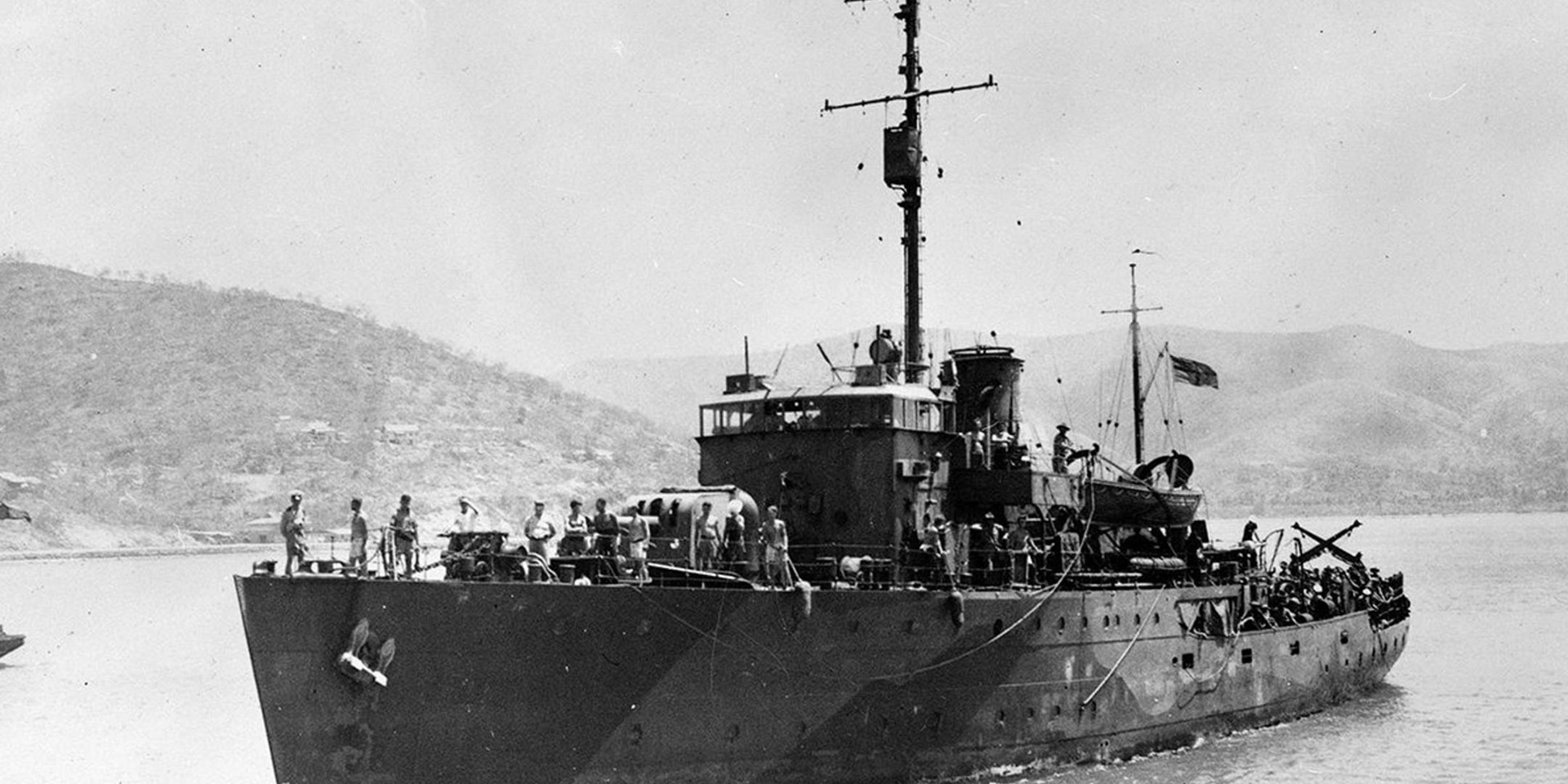

One of 60 Bathurst class minesweepers built in Australia during World War II, HMAS Armidale was laid down on 1 September 1941 at Mort’s Dock & Engineering Co Ltd in Balmain, Sydney. The corvette – as the minesweepers were more commonly called – was commissioned into the Royal Australian Navy on 11 June 1942. Six months later – on 1 December 1942 – the ship was at the bottom of the sea.

Commissioning of HMAS Armidale. Courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Armidale’s initial wartime service was as an escort vessel protecting convoys moving between Australia and New Guinea. The Japanese had already taken the Malay Peninsula, Singapore, Java, Timor and New Guinea – islands to Australia’s north that could be seen as jumping off points for an attack on northern Australia. The work of the convoys in supplying goods, equipment and personnel was vital.

In October 1942 Armidale was ordered to Darwin to join the 24th Minesweeping Flotilla; arriving there on 7 November. On 24 November the Allied Land Forces HQ approved the evacuation and relief of the Australian 2/2nd Independent Company which was operating as a guerrilla force in Japanese-occupied Timor, and suffering from malaria and chronic dysentery. The operation also included the withdrawal of Portuguese civilian evacuees and 176 Netherlands East Indies troops from Betano Bay on the southern shores of Timor.

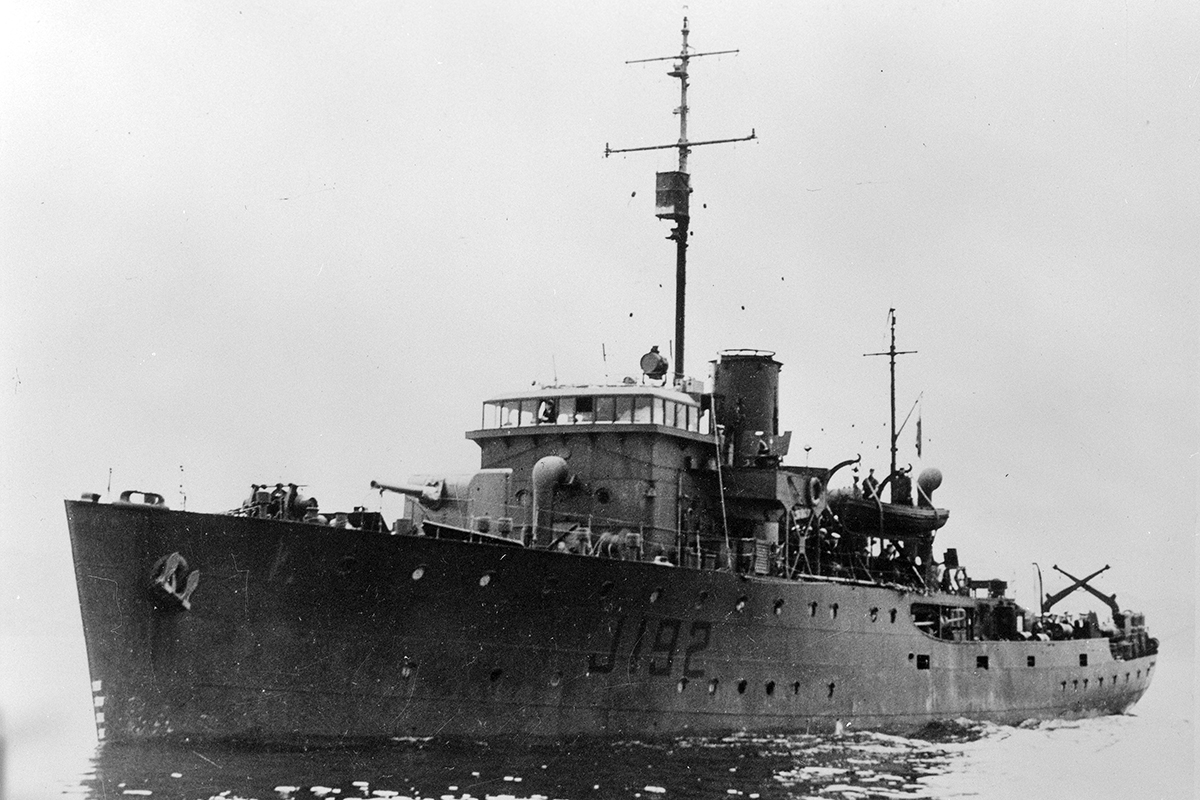

HMA Ships Armidale,Castlemaine (also a corvette) and Kuru were tasked with the resupply and evacuation operation. Kuru was a 23.2-metre (76-foot) former customs and police patrol wooden motor vessel which had been requisitioned in 1941 and was part of the ‘Timor Ferry Service’ running supplies, troops and equipment under cover of darkness to Timor and returning with evacuees.

HMAS Kuru. Courtesy Royal Australian Navy.

HMAS Armidale and Kuru came under attack

Kuru left Darwin on the night of 28 November with Armidale and Castlemaine leaving the following day. On board Armidale were three members of the 2nd AIF and 61 Javanese commandoes under the command of two Dutch officers. On the 30th both corvettes came under aerial attack from a single aircraft, having been spotted leaving Darwin by Japanese reconnaissance aircraft. Although they suffered no damage, there was concern that their mission had been compromised. However, they were ordered to proceed and Bristol Beaufighters were sent to provide aerial cover. The ships came under attack twice more, each time by formations of five bombers which dropped some 45 bombs, and also machine gunned from a low level. The Beaufighters drove off the enemy aircraft and, despite minor damage, the ships reached Betano at 3.30 am on 1 December but no-one was waiting. They left without landing the troops.

Kuru in the meantime had embarked 77 Portuguese women and children at Betano and was sailing south when she met up with Castlemaine. Just as the transfer of the Portuguese from Kuru to Castlemaine was completed, enemy bombers appeared again, forcing the ships to seek cover in a nearby heavy rain squall.

Armidale and Kuru were then ordered by the Naval Officer-in-Charge in Darwin, CDRE C J Pope, to return to Betano to complete the troop operation. Castlemaine headed back to Darwin, at the same time searching for two downed airmen from a Beaufighter.

Armidale and Kuru soon came under fierce aerial attack and became separated in the chaos. For almost seven hours Kuru was attacked by some 44 fighters, suffering damage to the engine when shrapnel penetrated the hull. Initially instructed by Darwin to complete the operation, Kuru was then ordered to return to Darwin after Japanese cruisers were reported to be in the area.

Unidentified crew members from HMAS Armidale. Courtesy Australian War Memorial.

The sinking

At about 1.00 pm HMAS Armidale was attacked by five Japanese bombers. Requesting air cover from Darwin, LCDR Richards was told fighters would be there at 3.45 pm. CDRE Pope famously signalled that ‘air attack is to be accepted as ordinary, routine, secondary warfare’. This type of warfare was undertaken exceptionally well by the Japanese air crews and Pope was later criticised for his apparent dismissal of aerial attack as being a significant element of warfare.

At 3.00 pm nine Japanese bombers, three Zero fighters and a float plane began attacking the single corvette. The fighters strafed the ship from low levels while the bombers attacked from different directions loosing their torpedoes at the gallant ship.

I had watched our gunner, Lou Lyndon, fire at the Zeros as they flew in low to machine-gun the ship. He seemed to be spot on, the tracers seemed to penetrate the planes’ windscreens and sides as they flashed over us, but the Japs didn’t hesitate. They just kept coming. Ordinary Seaman Rex Pullen

Manoeuvring desperately in an attempt to avoid the torpedoes, Armidale was struck by two and heeled sharply to port.

Most of the soldiers crowded into the mess deck were killed in that first blast. [They] would have felt this black, hopeless anguish before the sea rushed in. Ordinary Seaman Col Madigan

The order to abandon ship was given; rafts were cut loose and a motor boat freed before the men took to the water and Armidale sank.

Ratings were trying to get out lifesaving appliances as Jap planes roared just above us, blazing away with cannon and machine guns. Seven or eight of us were on the quarterdeck when we saw another bomber coming from the starboard quarter. It hit us with another torpedo and we were thrown in a heap among the depth charges and racks. We could feel Armidale going beneath us, so we dived over the side and swam about 50 yards astern as fast as we could. Then we stopped swimming and looked back at our old ship. She was sliding under, the stern high in the air, the propellers still turning. Leading Seaman Leigh Bool

In this time of terror one man’s actions stand out. Eighteen-year-old Edward ‘Teddy’ Sheean went down with the ship as a hero. Seeing his shipmates under attack, he strapped himself to his Oerlikon gun and fired continuously, sending one Zero into the sea. He was shot in the chest and back but still he kept firing, even as the ship sank. Sheean was posthumously Mentioned in Despatches but not recommended for the Victoria Cross as many believed he deserved (and are fighting for today).

Teddy Sheean (right) and his brother Mick. Courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Stranded and trying to survive

102 sailors and soldiers were now without a ship and their ordeal had just begun. Japanese airmen machine gunned the oil-soaked survivors before leaving the area – their work done. In the water, the survivors found themselves in dire straits. The motor boat, the damaged and submerged whaler and a Carley float were gathered up; fuel drums, painters’ planks and other flotsam were lashed together as a makeshift raft. The men clambered aboard as best they could although not all could fit. Sea snakes swam amongst them and sharks fed on the dead. In an effort to deter the sharks, the men would yell and scream and thrash the water when one came too close.

Right through that first night we heard the noise of water being disturbed. It was either sharks eating some of the bodies or blokes giving up and drowning. We did not know and it was better not to know. Telegraphist Denis Reedman

The sun was hellish by day but after sundown and during the night the air was freezing. No wonder we found a few missing at sunrise roll call. Ordinary Seaman Rex Pullen

When no rescue ship arrived, LCDR Richards made the decision to take 16 of the most badly injured of the ship’s company plus some fit rowers in the motor boat and head south for the Australian reconnaissance area; Timor was closer but certainly not safer. He had only a pocket compass and the stars to guide him. They were eventually sighted by an RAAF Hudson on 6 December and rescued by HMAS Kalgoorlie, another Australian corvette. Two of the men aboard the motor boat died before rescue arrived.

HMAS Kalgoorlie. Courtesy Australian War Memorial.

After some trouble with the Javanese soldiers, they and their Dutch officers were given the Carley float; they floated away and were never seen again. The 8.8 m (29-foot) whaler was in bad condition and in a feat of exceptional ingenuity it was docked with the raft and the holes patched and plugged with canvas, rag and even clothing. The whaler held 26 RAN and three AIF personnel and on 5 December under the command of LEUT Lloyd Palmer it left the half-submerged makeshift raft and the men began rowing to Australia – 470 kilometres away.

Day 6 for the whaler crew was, if anything, worse than Day 5. Of course, we were quickly using up our energy and our sores were getting worse. Even to hold the oar was an effort with our cracked, swollen and festering hands. How long could we last? Ordinary Seaman Rex Pullen

Rescue

On 7 December the raft was sighted by a searching Catalina aircraft. On 8 December both the raft and the whaler were seen by a Catalina but the sea was too rough to land. Aboard the whaler, food and water ran out; the men drank urine and tried to catch fish and gulls with their bare hands.

He recalled a tin of bully beef divided up into half-inch cubes and handed out … Then a sip of water, or condensed milk – then nothing. The belly shrunk, no evacuation, no water – could he drink his urine? Put it in that condensed milk can and woof [sic] it down; it was still warm, it made him retch. Ordinary Seaman Col Madigan

No food or water to speak of was quite evident. I was looking into faces covered in despair – and oil – and the eyes were sinking back into their sockets. Ordinary Seaman Rex Pullen

Ulcers and severe sunburn plagued them and they suffered delusions and were disoriented. On 9 December parcels of food and water were dropped by Hudson bombers as they waited for rescue. Some three hours later HMAS Kalgoorlie appeared and put its scrambling nets over the side for the Armidale men. Eight days after the sinking they were a pitiful sight but had achieved an epic feat of survival under appalling conditions.

Our legs were like strips of liquorice and we had to be carried in to the mess deck where lovely hot soup or stew was being issued to survivors – for surely that’s what we were now! After a feed or as much food as we could manage, each one of us was carried to the showers where we sat or knelt on the deck while Kalgoorlie sailors helped us clean ourselves up. Boy, oh boy! – soap and hot water! What a combination! What a luxury! Ordinary Seaman Rex Pullen

They were a pitiful sight.Their condition was appalling, with sunburnt, blistered, ulcerated skin covered in caked fuel, oil and salt. Fred Still, HMAS Kalgoorlie

Twenty-eight survived the whaler voyage and as the Kalgoorlie crew lifted the whaler aboard it broke apart – they had been rescued just in time, having somehow rowed just over 200 kms, almost halfway to Darwin.

But the men in the raft were never seen again despite days of searching. The raft was in poor condition so it may have broken up although no wreckage was sighted.

It wasn’t really a raft, it was something made up, objects off Armidale’s deck. Rope, oil drums, French mine-sweeping floats, Denton floats, the small Carley raft and painting planks; these were all collected at dawn, after the first lonely night. Ordinary Seaman Col Madigan

There was hope that they had been taken as POWs but no record of them was ever found. The third explanation was that they were picked up by a Japanese warship and executed.

Last image of the raft survivors. Courtesy of Australian War Memorial.

Delayed help

The motor boat and whaler survivors were reunited in Darwin and spent several days in hospital. Those who were physically able soon resumed their war duties.

Why had it taken so long for ships to go looking for the Armidale? On 1 December Armidale signalled Darwin that it was being attacked and was in need of air support. After it was sunk the men assumed Darwin would conclude the worst and send a rescue ship. What they didn’t know was two Japanese cruisers had been sighted and all ships had been ordered to observe complete radio silence. It was assumed that Armidale was following orders. The three day delay meant more suffering for the survivors.

Of the 149 sailors and soldiers aboard HMAS Armidale, 49 survived the nightmare. Armidale’s service in the Royal Australian Navy lasted a total of only 173 days.

Credits

References

- Feature image: HMAS Armidale in Port Moresby. Courtesy Australian War Memorial.

- Survival at sea: In the whaler after the sinking of HMAS Armidale in 1942. A personal account by Rex Pullen

- Armidale ’42: Memory and Imagination – a survivor’s account, A collaboration between Survivor Col Madigan, Artist Jan Senbergs, Historian Don Watson, Macmillan, 1999

- HMAS Armidale – The Ship That Had To Die, Frank B Walker, Kingfisher Press, 1990

- Corvettes – Little Ships for Big Men, Frank B Walker, Kingfisher Press, 1995

- http://www.navy.gov.au/history

Acknowledgements

This story is part of the museum’s ‘War and Peace in the Pacific 75’ program.

Presented by the USA Programs of the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Funded by the USA Bicentennial Gift Fund.