A New Italy in New South Wales

In July 1880, Venetian couple Lorenzo Roder (1843–1931) and Maria Regina Roder (née Piai) (1855–1942) were among more than 300 Italian migrants that boarded the steamer India in Barcelona, bound for an idyllic new French settlement in the southwest Pacific Ocean. But when they finally disembarked from a disastrous three-month voyage, they were confronted by a desolate, malaria-infested mangrove swamp. They had been deceived by the Marquis de Rays.

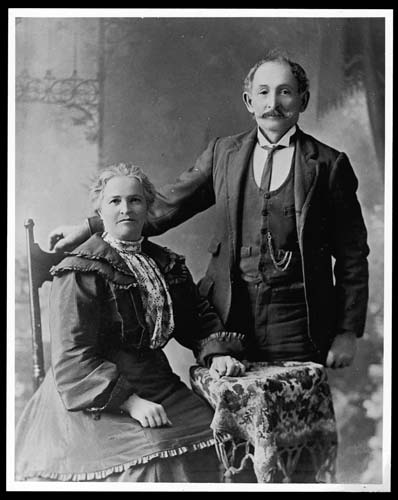

Maria and Lorenzo Roder in Lismore, New South Wales, c 1900. Reproduced courtesy Lorraine Lovitt.

Born Charles Marie Bonaventure du Breil in Brittany in 1832, de Rays aspired to establish a utopian society at Port Breton on the island of New Ireland (now part of Papua New Guinea). In the late 1870s the ambitious French nobleman launched a scheme to collect subscriptions for his imagined colony, which he called La Nouvelle France (‘New France’).

De Rays was an ardent follower of the journals of European explorers, and had travelled extensively in the United States, Senegal, Madagascar and Indochina during his youth. He regarded the colonising mission as a means of restoring the glorious past of his country, as well as his own privileged social standing, which had now been eroded in post-revolutionary France. Declaring himself King Charles I of New France, de Rays promoted the fraudulent scheme through newspaper advertisements and literature that extolled the virtues of his South Pacific paradise, with its fine buildings, wide roads, fertile soils and agreeable climate.

De Rays employed a Milanese emigration agent by the name of Edwige Schenini, who journeyed through the impoverished villages of northern Italy to recruit migrants for the venture. Participants were required to either pay 1,800 francs in gold or become indentured labourers for five years, in exchange for a four-room house and 50 acres of arable land, which would be cleared and ready for cultivation. For the contadini (peasants) of the economically depressed Veneto region, including the Roder family from the village of Orsago, this was an appealing prospect. Their farming existence had long been burdened by alternating periods of drought and flood, heavy taxes, and war between the Austrian Empire and the newly-formed Republic of Italy.

The Roder family farmhouse in Orsago, Italy, 1995. Reproduced courtesy Nancy Lovitt.

In early 1880, 27 members of the extended Roder family, including Lorenzo (37) and Maria (25), and their son Antonio (5), were among the 50 families assembled for a fresh start in La Nouvelle France. Complications surfaced early into the endeavour, when the Royal Investigation Bureau of Milan decreed that passports would not be issued to any Italians intending to join the Marquis de Rays expedition, due to concerns about the suitability of the proposed settlement site. But official forewarnings about the sterility of the land and the risk of death from starvation were not enough to deter the group. In April 1880 they managed to reach the French port of Marseilles, from where they were transferred to Barcelona, Spain. There they experienced miserable living conditions for several months, until they were finally able to obtain passports from the Italian Consulate.

On 9 July 1880, 340 migrants departed Barcelona on the third of de Rays’ four expeditions to Port Breton. Sailing on India under the command of Captain Jules Prévost, they were reassured that the passengers from the two earlier voyages of Chandernagore and Génil were already settled. The expedition began badly when Lucietti Buoro (née Roder), a widowed mother of two, died just nine days into the passage. Nine infants, including Agata Roder and Cristina Roder, died before India arrived at Port Breton on 14 October 1880. The migrants were greeted by the sight of Génil at anchor – but the promised settlement was not to be seen.

The industrious expeditioners promptly set to work to clear the land and plant crops, but tragedy and suffering soon ensued as food supplies ran short and the inhospitable foreign climate took its toll. Over the next four months, around 100 people died from disease and malnutrition, including Maddalena Roder (73), Giovanni Roder (76) and Giacomo Roder (42).

Tragedy and suffering soon ensured as food supplies ran short and the inhospitable foreign climate took its toll.

In December 1880, Captain Prévost sailed Génil to Sydney for provisions, but his return was delayed by engine repairs in Maryborough, Queensland. As the situation at Port Breton deteriorated, the settlers petitioned their interim leader, Captain Leroy, to transport them to Sydney. He decided to head for the closer French penal colony of New Caledonia instead.

The voyage to New Caledonia in February 1881 was beset by difficulties, and it was only because of the vigilance of passenger Angelo Roder that India avoided being wrecked on a reef. On 12 March 1881 India’s distressed passengers arrived in Nouméa, where they were offered food, water and fresh milk. But they were adamant about travelling to Sydney and appealed to Edgar Layard, the honorary British Consul in New Caledonia, for assistance.

Layard referred the group’s request to Lord Augustus Loftus, the Governor of New South Wales, and Sir Henry Parkes, the Colonial Secretary of New South Wales. Parkes responded favourably and arranged for the destitute Italians to be transported to Sydney on the steamer James Paterson. The 217 refugees arrived in Sydney on 7 April 1881 and were permitted to enter the colony as shipwrecked mariners. Parkes was later honoured by King Umberto I of Italy with the title of Commander of the Crown of Italy.

The survivors of the de Rays expedition were initially accommodated in the Agricultural Hall of the Exhibition Building in The Domain. They were then dispersed to labouring and domestic jobs throughout the colony – from Liverpool, Parramatta, Campbelltown and Penrith, to as far afield as Goulburn and Singleton – in an attempt to assimilate them into the community. However the group retained a deep-seated desire to reunite.

An opportunity arose in 1882 when Italian settlers Rocco Caminotti and Antonio Pezzutti selected 3,000 acres of land south of the Richmond River, near the town of Woodburn in northern New South Wales. By the end of 1883, 26 families from the de Rays expedition had relocated to the new settlement, which they named La Cella Venezia (‘The Venice Cell’). This became New Italy in 1884, when an application was made to open a school on the site.

The New Italians were highly respected throughout the Richmond Valley region for their dedicated work ethic. Using local materials such as bark, clay, and wattle and daub, they constructed their simple dwellings, followed by wells, ovens, cellars, a church, a school and a community hall. Timber getting provided the cash to raise livestock, while the settlers’ strong agricultural skills saw orchards, vineyards and vegetable gardens quickly flourish on land that the British deemed barren. The New Italy settlement was self-sufficient and its residents were extremely resourceful, using duck feathers to make pillows, corn husks for mattresses, and spinning and knitting wool on machines built by Angelo Roder. In the early 1890s they experimented with silk farming (one of the specialties of their homeland) and won prizes at international exhibitions in Chicago and Milan. Sericulture supplemented the other main industries in the region, namely timber getting, cane cutting, winemaking and dairying.

Going away party for the wedding of Maria and Lorenzo Roder’s daughter, Mary (front row, holding handbag), c 1921. Maria and Lorenzo are in the back row, third and fourth from right. Reproduced courtesy Pauline Lovitt.

By the turn of the century a number of butter factories, including Norco, were operating in the area, and cream boats were a common sight on the local waterways. The New Italians supplied cream to the butter factory in the busy port town of Coraki, located at the junction of the Richmond River and Wilsons River. Lorenzo and Maria Roder owned a dairy farm at Wyrallah, on the east bank of the Wilsons River, which they operated until they retired north to the town of Lismore. The couple lived well into their eighties and raised nine children – Antonio, Lawrence, Theresa, Giovanna, Andrew, James, Minni, Maria and Lucy – who all became loyal citizens of Australia. Their youngest son James served in the Australian Imperial Force during World War I. Lorenzo Roder died in 1931 and Maria Roder died in 1942. Lorenzo and Maria’s granddaughter, Nancy Lovitt, registered their names on the Welcome Wall to acknowledge all the hardships her forebears endured to reach Australia.

The New Italians were highly respected throughout the Richmond Valley region for their dedicated work ethic.

In the years after World War I, New Italy slowly lost its unique character as the ageing pioneers passed on and their descendants integrated into the community through schooling and intermarriage. The New Italy School was closed in 1933 and the settlement was abandoned following the death of its last resident, 87-year-old Giacomo Piccoli, in 1955. Today the New Italy Museum and Monument to the Pioneers stand as tangible reminders of the perseverance and resilience of the New Italians, along a stretch of the Pacific Highway between Grafton and Ballina.

And what became of the Marquis de Rays? In 1882 de Rays was arrested in Spain and extradited to France, where he was tried and sentenced in 1884 to four years’ imprisonment. He had amassed a wealth of more than seven million francs through four failed expeditions to the South Pacific. Upon his release from prison in 1888, de Rays engaged in a few more dubious adventures before he died in 1893, having never set foot in La Nouvelle France.

This article originally appeared in Signals Magazine (Issue #121).