Honoring a family empire

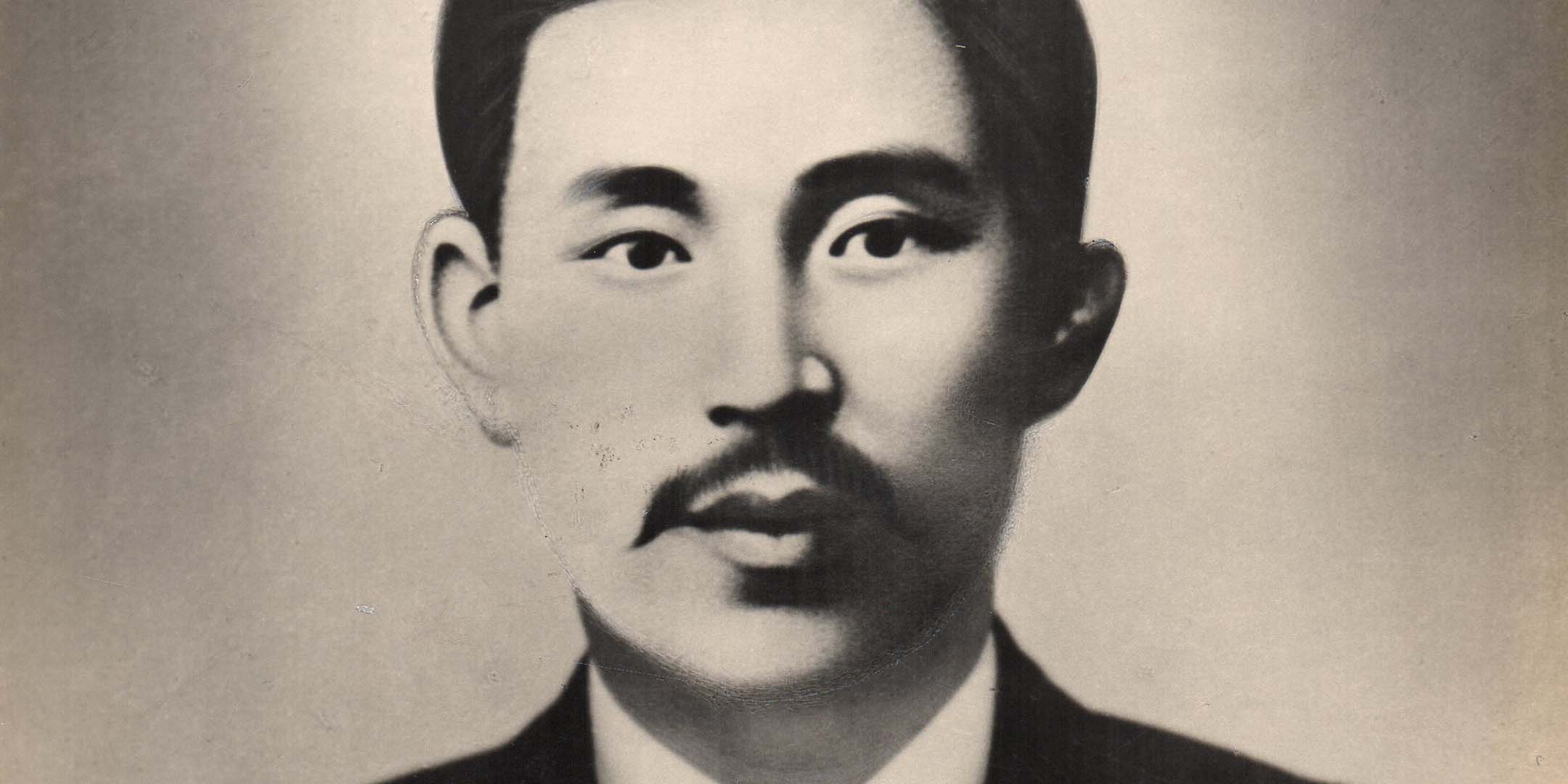

Gock Quay (1878–1916) was born in the small farming community of Chuk Sau Yuen in Xiangshan county (now Zhuxiuyuan, Zhongshan), in southern China’s Guangdong province. Today Zhongshan (meaning ‘Middle Mountain’) is best known as the birthplace of revolutionary leader Dr Sun Yat-sen, but from the mid-19th century it was also a major source of Chinese migrants and sojourners seeking their fortunes on the Australian goldfields.

Gock Quay was the fourth of six sons, and arrived in Australia at the age of 12 to join his older brothers, Gock Lok and Gock Chuen. Gock Lok, who was the first to land in the New Gold Mountain of Victoria, quickly discovered that the streets of Melbourne were not paved with gold. Without any English, and with little experience beyond that obtained on his father’s farm, Gock Lok headed to Sydney where he worked as a market gardener and then a vegetable hawker. This humble beginning would eventually grow into a multi-billion dollar family empire, Wing On (meaning ‘perpetual peace’) – a diverse group of companies that operated greengrocers, banks, department stores, warehouses, hotels, textile and knitting mills, and insurance offices in a vast commercial network stretching from Sydney to Hong Kong, Macau and Shanghai.

Gock Lok quickly discovered that the streets of Melbourne were not paved with gold.

In the 1890s, as the Wing On business expanded, Gock Lok and Gock Chuen were joined in Sydney by their younger brothers, Gock Quay and Gock Son. The four brothers learnt English from a Chinese pastor and converted to Christianity, taking on the English baptismal names James Gock Lok, Philip Gock Chuen, Paul Gock Quay and William Gock Son.

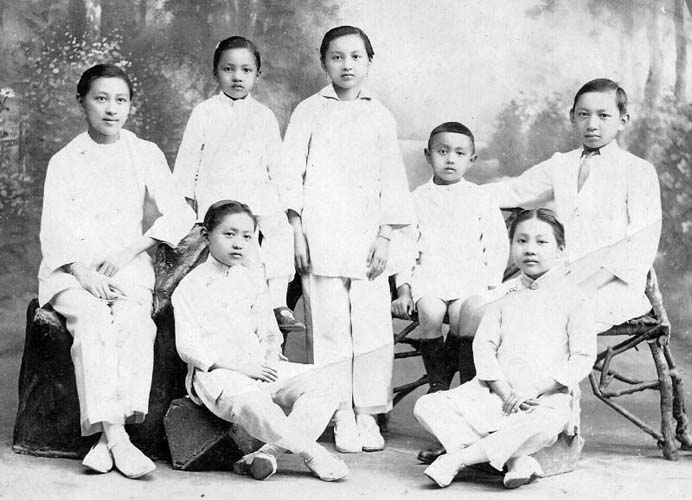

Immigration records show that Gock Quay lived in Parramatta, Hay and Sydney, New South Wales, before his arranged marriage to 17-year-old Rose Fok in Hong Kong in 1903. The couple returned to Sydney in 1904 and resided at 8 Mary Street, in the inner-city suburb of Surry Hills. Their seven children – David, Doris, Ada, Gladys, Violet, Marjorie and Edward – were all born in Sydney.

Rose Fok in Hong Kong, c 1903. Reproduced courtesy Paul Kwok.

In 1907 the Gock brothers opened the highly successful Wing On department store in Hong Kong’s Central district. They also owned godowns (warehouses) and the Great Eastern Hotel in Hong Kong, along with hotels in Canton (now Guangzhou) and Wuchow (now Wuzhou). As their wealth grew, the brothers did not forget their home village of Chuk Sau Yuen, where they helped to build a hospital and school, install irrigation and surface the roads.

With the overthrow of the imperial Qing dynasty in 1911 and the subsequent establishment of the Republic of China, the Gock brothers decided to extend their business to the mainland. Gock Quay was dispatched to the cosmopolitan treaty port of Shanghai to purchase a block of land for a new department store. He then returned to Hong Kong but in September 1916 sent a telegram to the Wing On office in Sydney that read, ‘Tell my family come to Hong Kong.’ Within a fortnight, his wife Rose, two sons and five daughters, ranging in age from two to 12, departed Sydney on St Albans. They were accompanied by Rose’s sister-in-law Flo, the wife of Gock Son, who helped to care for the children. Sadly Gock Quay died of an illness in November 1916, just weeks after his family’s arrival in Hong Kong, and did not see the opening of the grand new Shanghai emporium on Nanking Road (now Nanjing Lu). Following his death, Rose and the children remained in Hong Kong, later moving to Shanghai.

Edward Kwok (third from right) with his six siblings, late 1910s. Reproduced courtesy Paul Kwok.

This humble beginning would eventually grow

into a multi-billion dollar

family empire, Wing On.

In the years preceding World War II, the Gocks decided to anglicise their surname to Kwok. This reflected the opening of Wing On offices in San Francisco and New York, and also the fact that their children were attending western educational institutions. In the early 1930s, Gock Quay’s youngest son, Edward Kwok (1914–2003), studied at Queen’s College and the University of Hong Kong before enrolling in a textile chemistry course at Manchester College of Technology in England. In 1934, Edward met Edith Spliid (1916–2003), a proud Cockney born within earshot of Bow Bells to a Danish father and English mother. Prior to his return to the family textile mills in Shanghai in 1937, Edward informed the Spliids that he wanted to marry Edith.

In September 1937, a naïve 21-year-old Edith sailed from England on the Comorin, bound for Hong Kong. She arrived on the morning of 14 October and married Edward at St John’s Cathedral the same afternoon. The newlyweds lived with Edward’s sister Gladys and her husband, until Edward was called back to the family business in Shanghai by his brother David. Edith initially found Shanghai to be overpowering and lonely, but she gradually settled into family life with the arrival of three children, Paul (born 1938), Pamela (born 1940) and Peder (1943–2012).

Edward Kwok and Edith Spliid in England, 1935. Reproduced courtesy Paul Kwok.

On 8 December 1941, Edward and Edith were attending a family birthday party when they heard loud noises coming from the waterfront. An announcement was made that the Japanese were attacking Shanghai. At 10 o’clock the next morning, Edith watched on with sadness and fear as Japanese forces entered the city. The Kwok family textile mills were taken over by the Japanese, so Edward went to work extended hours at the Wing On offices in Nanking Road, leaving Edith alone with the children for long periods.

In 1942 residents of the Shanghai International Settlement (formed through the merger of the British and American settlements) were required to register with the police as enemy aliens. Their property was confiscated and assets frozen. The following year, enemy aliens were sent into the internment camps – a fate that Edith narrowly avoided as her father was born in Denmark, which made her a neutral national. She had to wear a red armband marked with the initial of her country and an identification number, and although free to move about with her children, she lived in constant fear. On one occasion, Japanese soldiers armed with rifles entered the family’s home demanding to see their papers, but fortunately no one was harmed.

In August 1945, the war ended and the Nationalist government took control of the International Settlement, the French Concession and other districts of Shanghai. Life was difficult and food was scarce, and inflation reached a critical point, prompting financial reforms and the introduction of a new currency.

In April 1949, Edward and Edith were booked to travel to Hong Kong with their youngest son Peder, leaving Paul and Pamela behind with friends. But when Communist forces crossed the Yangtze River and captured Nanjing, it was decided that the whole family should depart together. In Hong Kong they lived in a house owned by Edward’s brother, David, in Stanley.

In September 1949 David insisted that Edward return to Shanghai. Edith and the children followed in 1950, to a much changed city. With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China under Mao Zedong in October 1949, Wing On was forced to close its banking, insurance and textile businesses employing more than 20,000 people. The iconic Wing On department store in Shanghai was nationalised and renamed Hualian (now Yongan). All aspects of daily life in Shanghai were controlled by the Communist government and people were not permitted to stay away from their place of residence for even one night without seeking prior approval. The popular Chinese game of mahjong was banned, spying was rife and Maoist propaganda blared from loudspeakers across the country.

In 1952 the family began the process of applying for exit permits, which became increasingly crucial in the lead up to eldest son Paul’s 18th birthday and the looming threat of his conscription into the People’s Liberation Army. The family was finally granted a permit in November 1956 and the following month departed Shanghai for Hong Kong, sailing via Tsingtao (now Qingdao).

The Kwok family in Shanghai, Christmas 1955. Edith and Edward are seated with their three children (left to right) Peder, Paul and Pamela. Reproduced courtesy Paul Kwok.

In Hong Kong, Edward and Edith arranged a job for Paul in a textile mill owned by friends on Castle Peak Road. Paul did not like the work, however, and found a position with a company that produced window-fitted air conditioning units. Around this time he met Maunie Bones through the Vespa Club of Hong Kong. In January 1959, Paul and Maunie were married at St Andrew’s Church in Kowloon. Their first two sons were born in Hong Kong – Stephen (born 1959) and Christopher (born 1963).

Paul later joined the British firm, Gilman & Co, which promoted and exported Hong Kong manufacturing to the world. This was followed by positions in Christchurch, New Zealand, and then Sydney, where Paul and his family have remained since arriving in August 1964. In Sydney, Maunie gave birth to two more sons, Kevin (born 1965) and Derek (born 1969). Paul and Maunie now have 13 grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.

Paul’s parents and siblings also made the decision to move to Australia – Peder in 1964, Edward and Edith in 1969, and Pamela in 1978. Pamela has two children, three grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. Peder is survived by three children and two grandchildren. The four generations of the Kwok family now living in Australia are proud to have the opportunity to visit Darling Harbour to view the name of their pioneering ancestor, Gock Quay, on the Welcome Wall.

With thanks to Paul and Maunie Kwok for their assistance with this article.

This article originally appeared in Signals Magazine (Issue #119).