In 2003 museum staff completed the first Vessel Management Plan for Tu Do and commenced a program to restore the vessel to its appearance in 1977 – the most significant period in the boat’s history. It was around this time that we received the tragic news that Tan Lu had died during a business trip to Vietnam. The restoration program took on even greater meaning – it became a way of preserving Tan’s legacy as well as documenting the arrival of the first Indochinese boat people in the late 1970s.

This was a period of great social change in Australia. The Vietnamese initially received a warm welcome from Australian authorities, and their arrival coincided with major shifts in immigration legislation, including the final dismantling of the White Australia policy that had been in place since 1901. Tu Do provides a fascinating contrast to more recent unauthorised boat arrivals in Australia, which have contributed to a growing culture of fear in both the political and public discourse. This modest fishing vessel remains a powerful vehicle through which we can examine past and present immigration debates that are a central part of our maritime history.

Shipwrights Michael Whetters and Ron McJannett during extensive conservation and repair work to Tu Do’s hull, 2004. Photograph by Andrew Frolows/Australian National Maritime Museum

The Tu Do restoration program was developed by a team comprising curatorial and conservation staff, together with staff of the museum’s fleet section, which has the important (and very large) task of maintaining our floating collection – one of the largest and most challenging of any maritime museum in the world. The Tu Do program was underpinned by extensive research into Vietnamese fishing boat construction and wooden boat restoration, as well as oral histories and discussions with the Lu family, interviews with subsequent owners, and Michael Jensen’s photographs of Tu Do arriving in Darwin in 1977.

The first stage of the program (2003–08) involved repairing and stabilising the vessel, while trying to retain as much original fabric as possible. Tu Do’s wheelhouse was removed for strengthening on shore, under cover, and the powerful Jinil diesel engine that had been installed to outrun pirates was restored with parts sourced in South Korea or manufactured by museum shipwrights.

Shipwrights also removed Tu Do’s deck to access its hull structure and replaced damaged sections of the framing and planking with Australian hardwoods, which have similar properties to the original South-east Asian timbers. Shipwrights utilised techniques that were consistent with those of the builder and its era of construction, such as using trunnels (wooden pegs) instead of nails. Once the internal structure was sound the deck planking, restored engine and wheelhouse were reinstalled, making Tu Do the only fully operational refugee boat displayed on water in Australia.

The Lu family back on board Tu Do, 2005. Left to right: Mo, Dzung, Dao, Tuyet and Quoc Lu. Photograph by Andrew Frolows/Australian National Maritime Museum

Reconstruction and repainting

The second stage (2009–12) involved reconstruction and repainting, and relied heavily on the visual evidence in Jensen’s photographs. Elements identifiable in the photographs included an awning over the deck, supported between the mast and cabin by a beam, tree branches and bamboo poles; makeshift timber barricades on the port side of the vessel; a trawl winch on top of the cabin; and a very basic plank toilet at the stern – nothing more than a small wooden platform enclosed by a hessian sack for privacy.

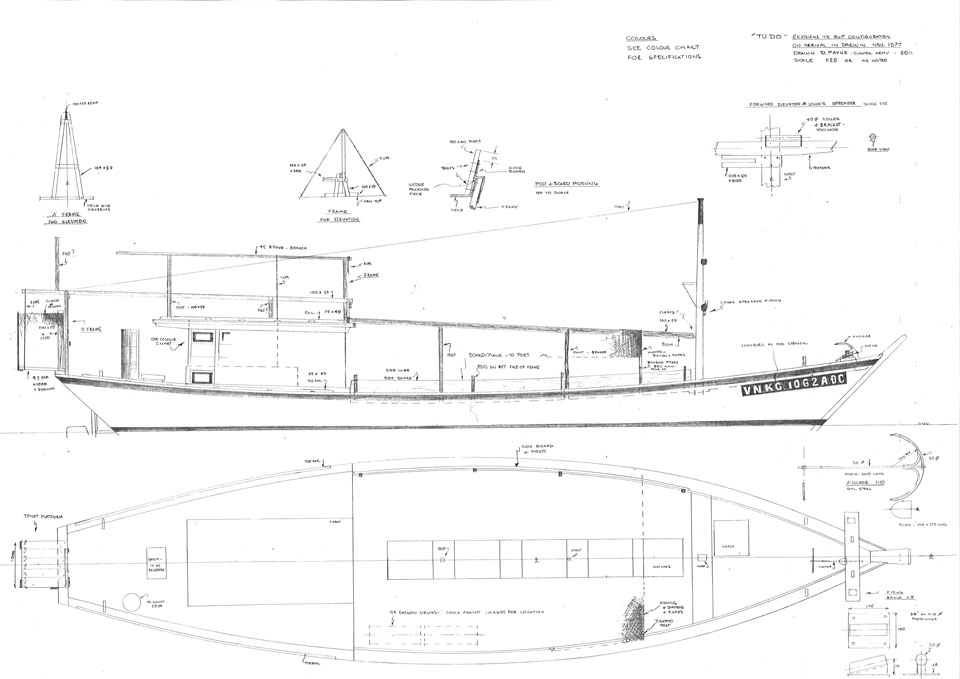

Tu Do revisions to suit the vessel’s configuration on arrival in Darwin in 1977. Plan drawn by David Payne/Australian National Maritime Museum, 2011

Plans were drawn up by curator David Payne to show the design and dimensions of each element, as well as its position on the vessel as determined from the 1977 photographs. Our fleet team scoured different timber yards to find replacement timbers and weathered boards, and also sourced props such as branches, bamboo, steel drums, a tarpaulin and old rope to dress the vessel. As elements were constructed and installed on deck, Tu Do’s original configuration slowly re-emerged. The final step was to return the vessel to its arrival colour scheme.

After arriving in Australia Tu Do was painted several times by its subsequent owners, and was delivered to the museum in 1990 with a white hull and a multi-coloured cabin reminiscent of various South-east Asian fishing boat styles, but not the colours with which the boat arrived in Darwin. Museum conservators took paint samples to trace back the chronology to the original colour scheme. Using these samples and information gleaned from interviews with the Lu family, we were able to construct a detailed paint scheme for Tu Do. The Jensen photographs, although black and white, were helpful in determining the different paint tones, while research into Vietnamese fishing boat livery provided a background to traditional trims. Once Tuyet Lu and her eldest daughter Dzung identified the correct sky blue colour from paint charts we were ready to commence painting.

Shipwrights Tom Kershaw and Matt McKinlay prepare to paint Tu Do’s hull, 2012. Photograph by Phil McKendrick/Australian National Maritime Museum

Shipwrights Tom Kershaw and Matt McKinlay prepare to paint Tu Do’s hull, 2012. Photograph by Phil McKendrick/Australian National Maritime Museum

Tu Do was slipped at a boatyard in North Sydney, where shipwrights painted its hull blue with a coat of red anti-fouling paint below the waterline. The vessel registration number ‘VN,KG,1062A,DC’, identifying it as a motorised fishing boat of Vietnam’s Kien Giang province, was painted on the bow. The numbers added up to nine – Tan’s lucky number. Tu Do was then returned to the museum’s floating vessel marina, where shipwrights completed the paint work on the deck, cabin and mast. Trim details were added, such as white beading around the wheelhouse panel frames and red on the gunwale, mast and stem. Finally replica fuel drums were installed on deck, fishing nets were suspended from the winch mechanism and a tarpaulin was fitted over the reconstructed awning to restore Tu Do to the configuration photographed by Michael Jensen when it docked in Darwin on a steamy November day in 1977.

Shipwright Tom Kershaw, apprentice shipwright Clarke Prior, apprentice boiler maker Ben Daley and shipwright and painter Teresa McKinlay dress the restored Tu Do at the Australian National Maritime Museum, 2012. Photograph by Kim Tao/Australian National Maritime Museum

Shipwright Tom Kershaw, apprentice shipwright Clarke Prior, apprentice boiler maker Ben Daley and shipwright and painter Teresa McKinlay dress the restored Tu Do at the Australian National Maritime Museum, 2012. Photograph by Kim Tao/Australian National Maritime Museum

For me it was a defining moment as I watched the museum’s fleet team install the tarpaulin, huddling beneath the low canopy as they tied up the ropes. I imagined the conditions as Tan and his crew assembled this makeshift shelter out on the open sea, having risked everything on a voyage into the unknown. It brought home the terrifying reality of their escape and validated the Australian National Maritime Museum’s rationale for restoring Tu Do. As the issue of unauthorised boat arrivals continues to dominate political and public debate, Tu Do stands as testament to the courage, hope and ingenuity exhibited by Tan, his family and their fellow passengers. It provides museum visitors with a compelling, tangible insight into the nature of refugee journeys and their enduring impact on individual lives.

For Tuyet Lu, who still lives in northern NSW, the restored Tu Do evokes mixed emotions. When she saw photos of the boat recently, Tuyet was reminded of how grateful she was to arrive in Australia but also how sad she felt to leave her homeland for a country so far away. Above all she was reminded of her late husband Tan and their journey in a fishing boat called Freedom.

Tu Do is open daily at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Darling Harbour, Sydney.

Tu Do on display at the Australian National Maritime Museum, Darling Harbour.