Throughout the late 18th century, any lady or gentleman worth their barouche knew how to draw and watercolour. Traipsing through English country sides or European cities on the Grand Tour gave these wealthy amateurs the opportunity to capture romantic country scenes or some cultural de rigour. The ease of watercolour over other options such as oil painting or pastels saw it become extremely popular especially in Britain whose changeable weather preferred a quick drying medium. So significant did watercolour painting become between 1750 and 1850 that it became referred to as the British Golden Age.

Often trends are appealing and accessible enough on their own to cement their popularity, but the surge of watercolour painters during the late 19th century had a number of external forces working in its favour. The industrial age saw to it that much of what was once upper class became accessible to a much wider audience. What was once made to order and expensive could be mass produced at a fraction of the price, such as paint. The scenic countryside that was once the summer playground of the wealthy was now open to city dwellers for the price of a train ticket. People, particularly the middle class could now afford to be aspirational. They could afford to replicate those habits and tell-tale signs of wealth that had been so out of reach only decades before. Watercolour painting, like many other arts, so peripheral to everyday life and a trivial pastime for most, represented a cosmic shift in British society and consumer behaviour.

'From verandah, Lauraville, Melbourne, William Field, Sketches of travels including voyages to Australia, 1870–82. National Maritime Collection, 00000950

Watercolours also represented something significant to Henry “Old King” Cole. In 1852 Cole was appointed head of the Department Practical Art in London and hell bent on his mission to bring art, design and beauty to the British masses, no matter what class. He became most widely known, along with Prince Albert, for the formation of what would become the Victoria and Albert Museum. A lesser known achievement was Cole’s introduction of the Shilling Paint Box. He appointed paint maker Joshua Rogers to produce a pocketsize watercolour paint set with brushes and palette, to be affordable for the working and middle classes. So confident was Cole in this proposal that The Society of Arts offered to purchase 1000 of the sets if the venture fumbled. There was no need and it is estimated that over the next decades over 7- 11 million Shilling Paint Boxes were sold. “Old King Cole” had proved again that background or education was no barrier to the appreciation of design and art. Thousands of amateur watercolourists sprung up capturing scenes of everyday life in Britain that had not been seen before.

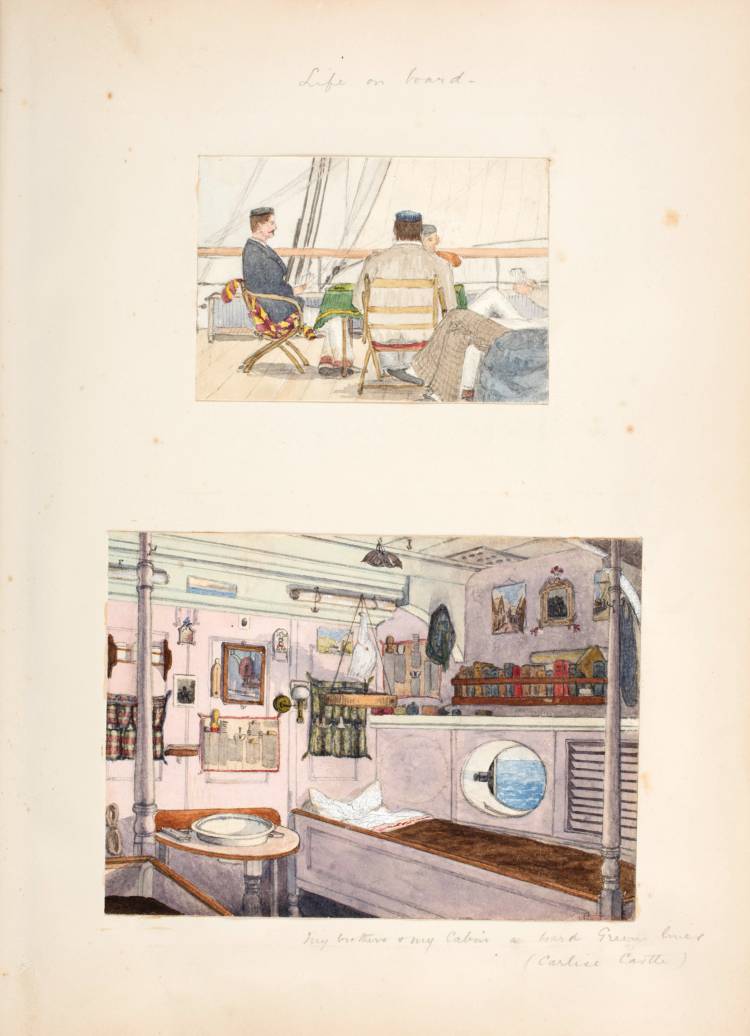

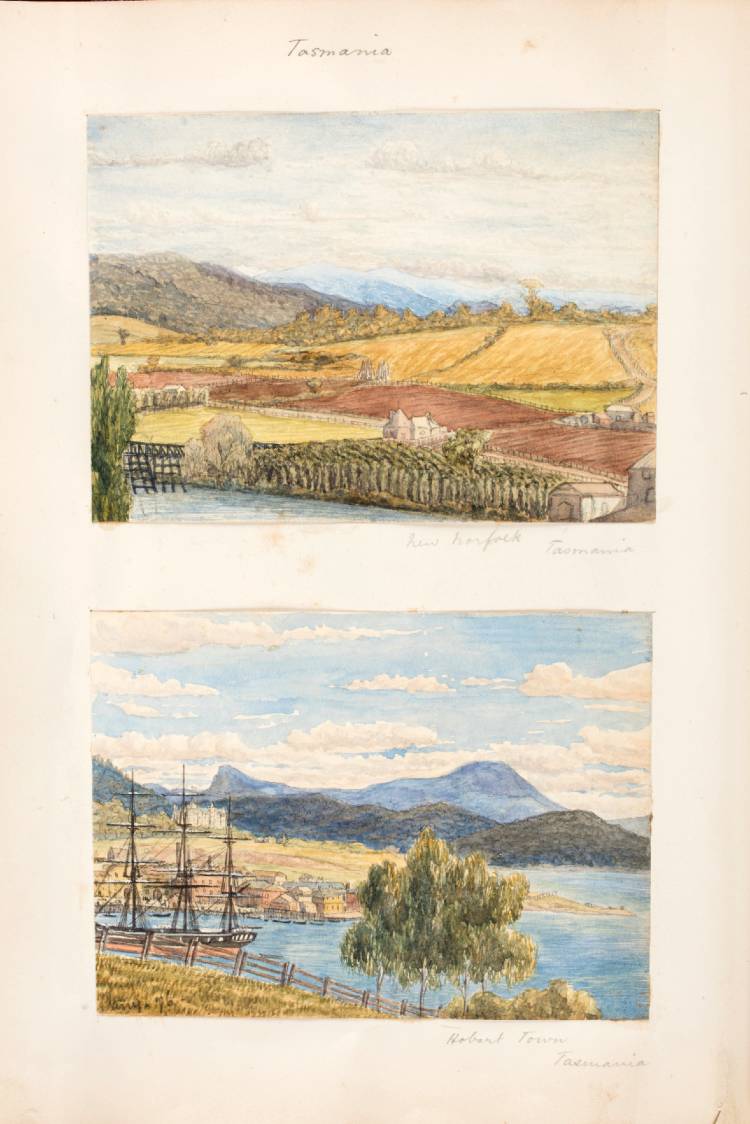

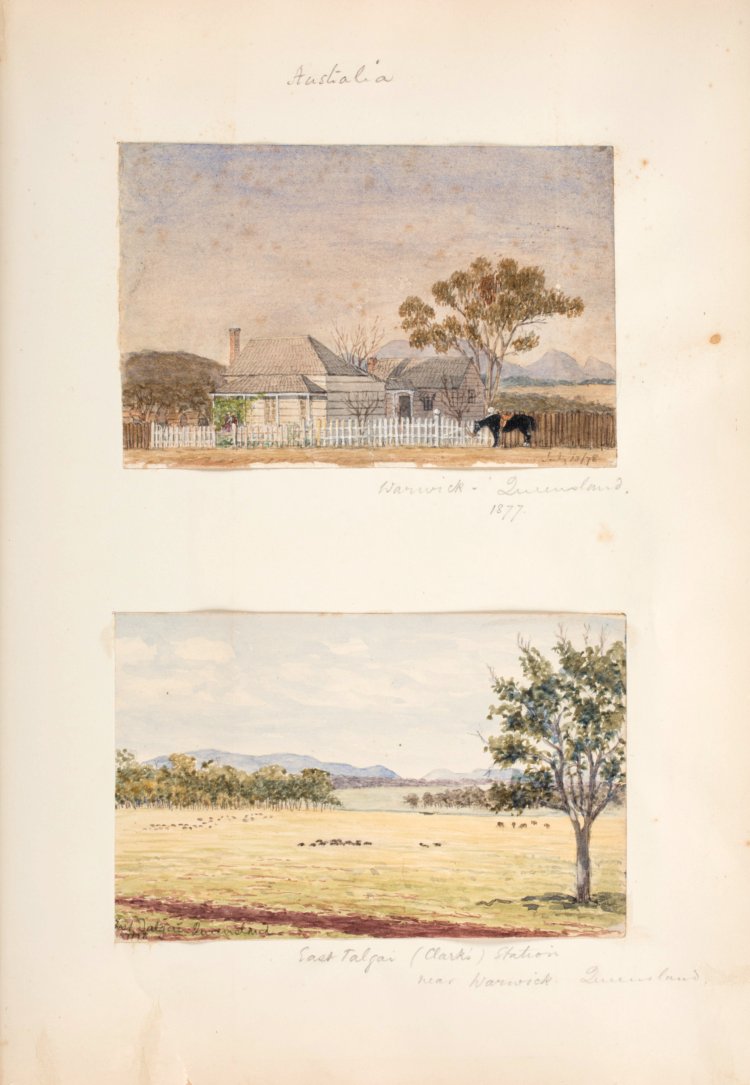

William Field was one such amateur. William and his brother Edward were part of the British middle class that were enjoying the educational and leisure benefits once solely the domain of the wealthy. The Field boys grew up in a modest home in Warwickshire and in 1875 boarded the Carlise Castle for an adventure to Australia. William had been an avid watercolourist before his Australian voyage, painting scenes of the family home and surrounds, even the family dog. Although photography was becoming more available at this time, it was an expensive and burdensome hobby and watercolour remained the choice for capturing opportune moments. William kept a sketchbook of his travels which is now part of the National Maritime Collection, and through these captured scenes there are moments not unlike those that would appear on an Instagram account today. The interior of William and Edward’s ship cabin, the veranda of a suburban Melbourne house or sweeping shipboard sunsets.

It is thanks to watercolour amateurs like William that these small records of life remain. They may never hang in galleries but Henry Cole, William Field and the thousands of other painters never intended them to. It was the everyman’s medium used to encourage people to see their lives in colour, capture what they loved when the moment presented itself.