While this year marks the 75th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Australia and the Philippines, our migrant connections date back to the second half of the 19th century, when Filipino divers (known as ‘Manilamen’) were recruited for the booming pearling industry in northern Australia.

A free-spirited adventurer, Filipino-born Telesforo Ybasco (1879–1972) loved the water. By the age of 17, he had already left his hometown of Daet, capital of the province of Camarines Norte, to travel the world on a sea freighter. In 1896 Telesforo landed in Broome, the Western Australian coastal town that by the turn of the century would become the pearling capital of the world.

Telesforo was lured by the prospects of deep-sea diving for the prized Pinctada maxima, the world’s largest pearl oyster. Today the species is cultivated to produce lustrous South Sea pearls, but in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the pearling industry was centred on harvesting pearl shell for the manufacture of mother-of-pearl buttons, buckles and fine cutlery.

Pearling lugger at work in Broome, Western Australia, c 1926. Photographer R A Bourne. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Pearl diving was a dangerous, and sometimes deadly, occupation and the industry relied heavily on indentured Aboriginal and Asian labour. The recruitment of Japanese, Chinese, Malay and Filipino divers from the 1880s saw Broome develop into a vibrant multicultural port town. By 1910, more than 400 pearling luggers operated out of Broome, carrying crews of hard-hat divers into deeper waters, and the town supplied about 70 per cent of the world’s pearl shell.

It was around this time that Telesforo Ybasco met Theresa Marques (1899–1979), who was born in Broome to a Japanese mother and a Spanish father. Despite their 20-year age difference, Telesforo courted Theresa and the couple married in 1917.

Theresa’s mother Omito (Omisca) Serotame had come from Japan as a teenager. Omisca married Basilio Marques in 1896 and sadly died soon after giving birth to their daughter in Broome’s infirmary. While Basilio wanted to raise baby Theresa on his own, Catholic mores of the day prescribed that a single parent – particularly a father – was not a suitable caregiver. The broader political climate was also one of growing intolerance towards ‘coloured’ people, reflected in the passing of the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901 and expressed in the ethos of the White Australia policy.

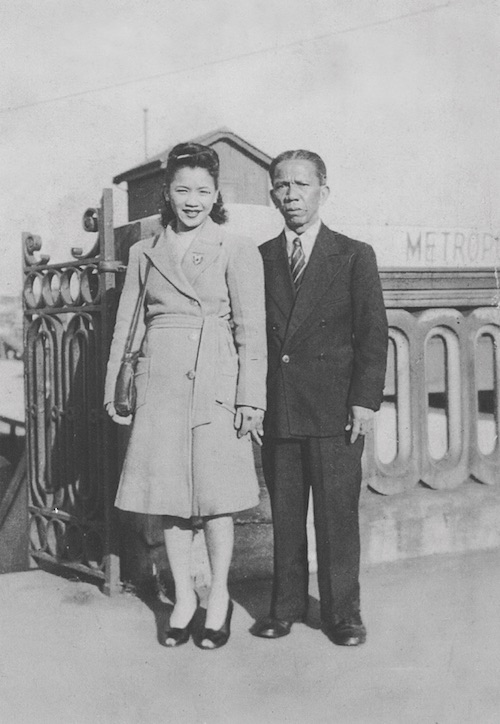

Theresa and Telesforo Ybasco in Broome, Western Australia, 1930s. Reproduced courtesy Cecilia Manalang-Spurrier

Basilio was forced to give Theresa up and she was placed in a Catholic mission at Beagle Bay, north of Broome. The mission was involved in the removal of children from Aboriginal or mixed-raced families before the Stolen Generations (1910–1970). Theresa finally left the Beagle Bay mission at the age of 17 and married Telesforo Ybasco.

Telesforo and Theresa had 12 children between 1918 and 1945. The five boys and seven girls – Joseph, Olivia, Mary, Paul, Anastasia, Magdalena, Theresa, Elizabeth, Peter, Rosemary, James and Martin – were all born in the upstairs bedroom of the family’s wooden cottage in Napier Terrace. Today the building is heritage listed and houses the Som Thai restaurant in the heart of Broome’s Chinatown.

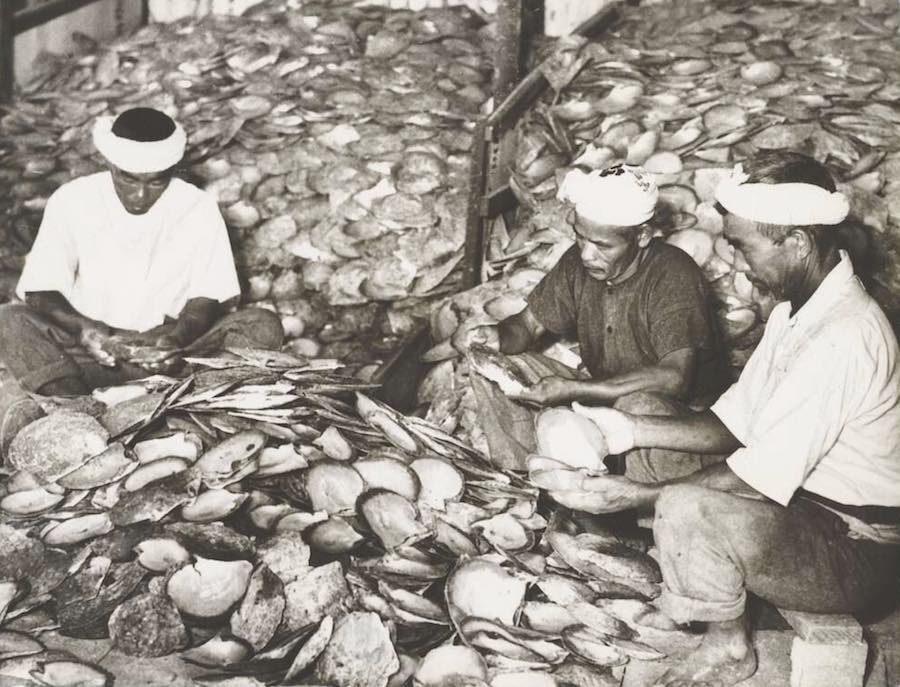

Grading and sorting mother- of-pearl shell in Broome, Western Australia, c 1953. Photographer Frank Hurley. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

With an expanding family, Theresa was reluctant for Telesforo to continue pearl diving, where the hazards ranged from ear and chest infections to shark attacks, cyclones and diver’s paralysis (or ‘the bends’, caused by bubbles of nitrogen gas forming in the blood and bodily tissues). Wearing a canvas suit, copper helmet and lead-weighted boots, Telesforo would dive up to 45 metres under water and walk along the seabed to collect pearl shell. Telesforo and Theresa’s seventh child, Theresa (born 1929 and known as Tess to distinguish her from her mother), remembers:

The physical rigours of diving and the inevitable toll it took on a diver’s body, including and especially internal organs such as the lungs and heart, meant my father’s occupation could not be sustained in the long term. In an early form of workplace health and safety, if not union mandating, divers were supposed to retire upon reaching 30.

Dad lasted in the water as long as his age would allow. His growing family dictated that he could not rest, however, so he learnt to cut hair and shave beards, becoming the only hairdresser in Broome in the early 1920s and 30s.

Telesforo operated his barber shop from the downstairs front room of the family’s home until the outbreak of World War II, when the Australian government ordered civilians to be evacuated from Broome to Darwin. Tess, who was 11 years old at the time, says:

I couldn’t understand why we would be sent [to Darwin] – indeed, this location further north may well have placed us in more peril, given its easier access from the north and the Japanese threat to bomb the Northern Territory port city [Darwin was attacked by the Japanese on 19 February 1942 and Broome was attacked on 3 March 1942, constituting the two worst air raids in Australia’s history].

The Ybasco family remained in Darwin for six months before they were forced to relocate again, this time to Perth. Tess recalls:

Leaving Darwin for Perth in 1940 was a nightmarish experience. The ship sailed under the darkness of night, only the moon casting any illumination. Lights could not be seen in case it might broadcast our location to the Japanese who, it was feared, could at any time launch an attack. It was in this darkness that we were told to be very quiet all the time we were on the ship.

In Perth, the family lived in a small house (now part of a row of shops) on the north side of the Horseshoe Bridge in the city centre. Telesforo opened a barber shop on William Street, near Perth’s central railway station.

In 1949 Telesforo and Theresa decided to return to the Philippines with six of their younger children. They ran a small takeaway shop in the capital, Manila. Telesforo died in 1972, aged 93, and Theresa died in 1979. In 1999, their daughter Theresa Manalang-Robertson registered Telesforo Ybasco’s name on the Welcome Wall to honour one of Broome’s pioneering deep-sea pearl divers and Manilamen.

The author wishes to thank Cecilia Manalang-Spurrier, Eugene van Prehn, Tina Ferrer and Deborah Ruiz Wall for their assistance with this article.

You can honour a migrant – yourself, a member of your family or a new arrival – on Australia's National Monument to Migration (formerly the Welcome Wall) at the museum.