Warning not heard or seen no help at hand

The wide dark bosom of the angry deep

With irresistible and cruel force

Received them all. One only cast alive

Fainting and breathless on the fatal rocks

To weeping friends and strangers afterwards

Thus told his melancholy tale.1

The 1850s were years of great social and economic growth in Australia, spurred on by the Australian gold rushes and corresponding increase in population, agriculture, industry and commerce. As the demand for goods and services grew, so did the demand for passenger and cargo ships. This persuaded Scottish shipowner and merchant Duncan Dunbar to order a series of hardwood clipper ships from the English shipbuilder James Laing and Sons of Sunderland, England, to cater for the new Australian trade. Credited with introducing the American-style clipper ship to the Australian run, Duncan Dunbar named the various clippers after his family including Phoebe Dunbar, Dunbar Castle, Duncan Dunbar and the Dunbar.

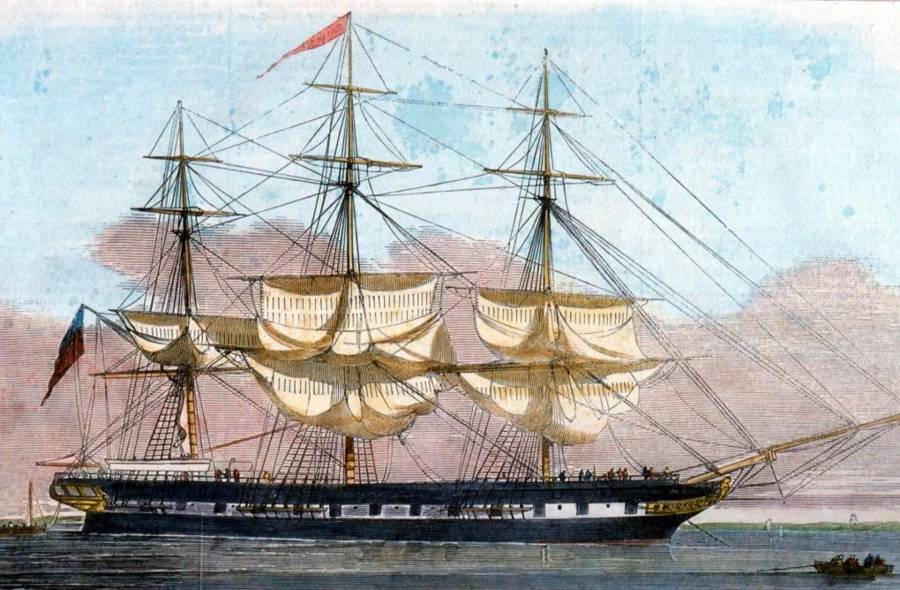

Hand-coloured wood engraving of the 'Dunbar' by the Illustrated London News, 1853. ANMM Collection 00000957

Built in 1852, the cooper-sheathed, three-masted sailing ship Dunbar cost over £30,000 and was designed to carry passengers and cargo quickly between England and Australia. The Dunbar was first requisitioned by the Royal Navy however, for use as a troop carrier during the Crimean War, so it wasn't until 1856 that it made its first visit to Port Jackson.

On 31 May 1857 the ship departed Plymouth for its second voyage to Australia, carrying 63 passengers, 59 crew and a substantial cargo, including dyes for the colony's first postage stamps, machinery, furniture, trade tokens (coins privately issued by traders and manufacturers as change and to promote their business), cutlery, manufactured and fine goods, food and alcohol. Many of the first-class passengers were prominent Sydneysiders, local 'currency' that had made it in the colonies and who, after a visit 'home' to England, were returning to Australia.

Dunbar's master Captain Green was a veteran of eight visits to Sydney, as first mate aboard the Agincourt and Waterloo, then as commander of Waterloo, and again commanding Vimeira and Dunbar. After a relatively fast voyage of 81 days, Dunbar arrived off Port Jackson on the night of Thursday, 20 August 1857, with a rising gale and bad visibility. The Macquarie Light on the cliff top a mile south of South Head was seen between squalls, although the night was dark and the land was invisible. Shortly before midnight Captain Green estimated the ship's position off the entrance to the Heads and changed course to enter, keeping the Macquarie Light on the port bow.

Captain Green then ordered a blue light to be burnt to summon the Sydney Harbour pilot. According to the only survivor – a sailor on watch at the time who became the sole source of information about events on board – the urgent cry of 'Breakers ahead!' was heard from the second mate on the forepeak. Captain Green gave the order 'Port your helm!' to swing the ship to starboard while the watch braced the sails.

It was already too late. Captain Green's orders instead drove the vessel broadside onto the 50-metre-high cliffs just south of the signal station at South Head, midway between the Macquarie Lighthouse and The Gap. The impact brought down the topmasts, mounting seas stove in the lifeboats and the Dunbar heaved broadside to the swells. Lying on its side, the ship began to break up almost immediately. The mizzen and main masts crashed over the side but the foremast remained standing.

One crewman, James Johnson, found himself in the poop clinging to the mizzen chains. Unable to cross the deck, which was being swept by each successive wave, he went below and made his way forward before climbing out of a cabin skylight and onto the chain plates of the surviving foremast. When the foremast finally gave way, Johnson was hurled onto the cliffs where he managed to gain a finger hold. Scrambling higher, he became the sole survivor amid a sea of bodies. All 63 passengers and the remaining 58 crew perished in the disaster.

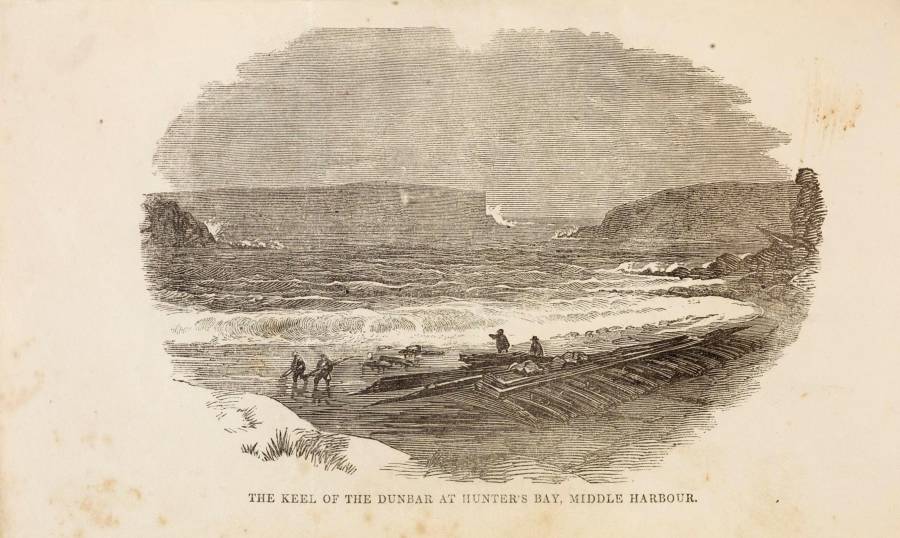

Illustration showing the keel of the 'Dunbar' at Hunter's Bay, Middle Harbour from the book, A narrative of the melancholy wreck of the Dunbar merchant ship ...', 1857. ANMM Collection 00009344

When dawn came, Johnson found himself on a rocky ledge some 10 feet above the wreck, surrounded by wreckage and dead bodies. From here he climbed up out of the reach of the waves and remained on the cliff face until being rescued on 22 August.

Dawn had unveiled the enormity of the event to the community of Sydney. Thousands were drawn to the scene of the wreck over the ensuing days to watch the rescue of Johnson, the recovery of the bodies and the salvage of some of the cargo. For days afterwards the newspapers, journals and local guides were filled with graphic descriptions of the wreck – and of the public's interest in the horrible 'spectacle'.

The rumours as to the fact of a dreadful shipwreck having just occurred soon assumed distinct shape and certainty. At length it generally became known in Sydney that numerous dead and mutilated bodies of men, women and children were to be seen floating in the heavy surf at the Gap thrown by immense waves at a great height; and dashed pitilessly against the rugged cliffs, the returning water sweeping them from the agonised sight of the horrified spectators ...2

To some, this spectacle would have been one of morbid curiosity, something to record in a diary or in a letter home to relatives in Europe, but to many, many others, once the wreck had been identified as the Dunbar, it would have been the need to identify or possibly recover the body of a father or mother, sister or brother or friend, that drew them to the scene of the disaster.

For the Dunbar was not just another ship carrying unknown immigrants starting a new life in Australia. On board were many local residents returning to the colonies after a visit to the old country, including eight members of the Waller family; Mr and Mrs Peek; Mrs Egan, the wife of the Sydney MP Daniel Egan; and Mr and Mrs Cahuac, son and daughter-in-law of the former Sheriff of Sydney.

Also on board were family members migrating from Europe to join family members in Australia such as the two Miss Hunts, the only sisters of Robert Hunt, the First Clerk of the Sydney Branch of The Royal Mint, who was a well-known colonial scientist and photographer.

Seventeen bodies, including some mutilated by sharks, were recovered on the north shore of Sydney Harbour from the Mosman Spit around to Taylors Bay. Some were identified immediately by names on their clothing or by personal appearance. But others were so badly mutilated they could not be recognised.

At Middle Harbour, the majority of the wreckage of Dunbar appeared to have drifted ashore, along with several bodies:

The shore is literally white with candles, and the rocks covered or so deep with articles of every kind – boots, panama hats and bonnets are here in abundance. Drums of figs, hams, pork, raisins, drapery, boots and pieces of timber are piled in heaps along with the keel of the Dunbar.

Never before, and probably never since, had a shipwreck off the coast of New South Wales had such a traumatic and long-term effect on the people of the colony.

The aftermath

The victims of Dunbar were buried at Camperdown Cemetery in O'Connell Town (near Newtown). The bodies of some unidentified victims were placed in a mass grave funded by the colonial government. Some 20,000 people lined George Street for the funeral procession that consisted of the band of the artillery companies, seven hearses, four mourning coaches and a long procession of carriages surrounded by a guard of honour provided by the Mounted Police Force.

Sydney's banks and offices closed for the service, church bells tolled, every ship in the harbour flew their ensigns at half mast and minute guns were fired as the seven hearses and over 100 carriages went past.

While the victims were being buried, conjecture was rife regarding the wrecking. The great loss of life led immediately to letters to the editor of The Empire and Sydney Morning Herald demanding the upgrading of the lighthouses at the Heads. The issues of lighthouses and pilotage were also raised during question time in Parliament, and were the matter of recommendations by the jury at the Dunbar inquest.

A small selection of the museum's Dunbar collection, purchased with the assistance of the Andrew Thyne Reid Charitable Trust

The calamitous shipwreck not only generated much speculation about the causes, but also a minor industry in memorialising the event. The wreck event formed the focus for several contemporary artists, including S F Gregory, Samuel Thomas Gill and Robert Hunt, who captured the terrifying scene through notable lightographs, paintings and photographs. Numerous poems, narratives and accounts were written, some published just days after the event.

Besides the pamphlets and brochures, other items began to appear as part of the memorabilia industry associated with the tragedy. Salvors had acquired bits of the vessel and were manufacturing all manner of items including a set of chairs marked 'Made from the wreck of the Dunbar' by Andrew Lenehan of Sydney. 'Church, House and Garden Furniture manufactured to any design from the wreck of the Dunbar in teak and oak' were advertised in the Sydney Morning Herald.3

More official and in most cases longer-lasting memorials were also built, including the one marking the mass grave in Camperdown Cemetery. A Dunbar memorial on the cliff top near The Gap was also established by the local government as a permanent memorial of the horrendous loss.

Two initiatives should also be considered memorials to the tragedy. One was the erection in 1858 of the red-and-white striped Hornby Lighthouse and the accompanying lighthouse-keepers' houses on South Head, immediately adjacent the entrance to Port Jackson and Sydney Harbour, which no doubt prevented other vessels from being cast ashore against the cliffs of South Head. And the wreck site itself became a memorial in October 1991 when it was protected under the Commonwealth Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976 due to its historical, archaeological and symbolic significance.

Artefacts from the Dunbar

Due to the exposed nature of the site near South Head, its shallow depth and the constant southerly swells that crash into the cliffs for most of the year, the Dunbar has been greatly reduced by the elements since August 1857. Nineteenth-century salvors, of course, tried to recover anything of value that they could reach. The archaeological remains have also been severely reduced due to the actions of salvage and recreational divers at the site since its rediscovery in the early 1950s, when scuba diving equipment became more readily available and affordable both to professional and recreational divers.

Without heritage legislation in force and with a lack of understanding of conservation science and heritage protection, the Dunbar and other wrecks in Australian waters were severely damaged by divers using many means, including explosives, to obtain materials from the wreck. In good weather and fairly shallow water, scuba divers were able to pick over the Dunbar site for trinkets – the many small, imperishable items such as coins and belt buckles, pipes and pocket watches and even gold dentures that spilled from smashed trunks and cabins and settled in crevices on the rocky seashore.

This was often accompanied by a misguided belief that they were preserving relics from the ravages of the sea, when in fact being brought up from the sea bed accelerated the deterioration of items that did not receive the appropriate conservation treatments. The divers' efforts also destabilised what was already a fragile site – the protective concretions that covered parts of the wreck were removed and the site was exposed further to the actions of the waves, sand and rock.

In 1991, the Dunbar and its associated relics were declared a historic shipwreck under the Commonwealth Historic Shipwrecks Act. This meant that the site was to be protected from any future unauthorised interference and subsequent damage. Two years later, in 1993, the Commonwealth Department of the Arts and Administrative Services declared an amnesty from prosecution to encourage people who had material from protected shipwrecks to come forward and declare that material.

As a result of this amnesty, John Gillies, an active sports diver in the 1950s and 60s, declared a collection of over 5,000 objects from the Dunbar wreck to the New South Wales Department of Planning. In August 1994 the department granted Mr Gillies a permit to dispose of his collection at auction under the condition that the collection be registered, photographed, remain in Australia and the new owner inform the department within 30 days of purchase.

Shortly afterwards, the Australian National Maritime Museum negotiated an out-of-auction settlement with Mr Gillies to prevent this important collection from falling into private hands and possibly being broken up. You can browse these various artefacts on our Collections website.

References:

[1] A narrative of the melancholy wreck of the Dubar by James Fryer, 1857.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 August 1857.