Fighting in both the battles of Camperdown (1797) and Copenhagen (1801), William Bligh proved to be a formidable opponent of Britain’s enemies, taking on larger and more heavily armed ships as his military prowess became clear.

The Battle of Camperdown

In 1795, after the establishment of the Batavian Republic in what is now the Netherlands, Bligh was appointed to command HMS Calcutta, and soon after the 64-gun HMS Director. The Batavian Republic was supported by French forces and the resultant threat of Dutch naval activities on Britain’s doorstep resulted in a call to action. Bligh was assigned under Admiral Duncan to blockade the Dutch fleet in their anchorage behind Texel island off the Dutch mainland.

Battle of Camperdown by Thomas Whitcombe, 1798. GL Archive / Alamy Stock Photo. In the centre of the picture is Admiral Duncan's flagship the Venerable, flying the blue ensign from the mizzen. The Vrijheid, to the left of the image, flies the Batavian ensign from the stern; it is still firing at the Venerable but its fore and mizzen masts are gone, and the main mast is on its way over the port side. In the right foreground is the Dutch ship Hercules, on fire aft, with its mizzen gone.

The blockade remained in place for the following two years, though briefly thrown into disarray in 1797 by the mutiny of many crews of British ships at Spithead (Portsmouth) and the Nore (Thames estuary), demanding better pay and conditions. Bligh’s ship, Director, was one of the ships involved and he was temporarily removed from command, then reinstated when the mutiny fell apart in June.

In October the drama of the Nore mutiny was replaced by what came to be known as the Battle of Camperdown, a reference to the Dutch coastal village of Camperduin close to where the battle took place. The engagement between the Dutch fleet of Admiral de Winter and the British fleet under Admiral Duncan was fought on 11 October, and resulted in a crushing defeat of the Dutch ships. Bligh’s ship played a significant role in the battle, engaging Admiral de Winter’s flagship Vrijheid and battering it into submission after a bloody onslaught in which all of the Vrijheid’s masts were blown away and many of its crew killed. De Winter was taken to Admiral Duncan’s ship, where he formally surrendered.

After the threat posed by the Nore mutiny, the victory at Camperdown was celebrated as proof that Britain’s much-vaunted navy had lost none of its will to fight and remained a force to be reckoned with. Bligh, along with all the other British commanding officers involved in the battle, was awarded a gold medal. Later, as governor of New South Wales, Bligh gave the name Camperdown to his land grant along the road to Parramatta.

The Battle of Copenhagen

An alliance of Denmark, Sweden, Prussia and Russia was threatening to assert their right of free trade to supply France. In response, the Admiralty sent a fleet under the command of Admiral Hyde Parker to Copenhagen to bolster a diplomatic mission aimed at persuading Denmark to rethink its position. When diplomacy failed, both sides prepared for battle.

The Battle of Copenhagen, 2 April 1801 by Nicholas Pocock. Niday Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

The battle was fought in the shallow waters just offshore from the city of Copenhagen. The Danish fleet was anchored parallel to the shore to maximise the effect of their broadside and were supported by floating gun batteries, powerfully armed hulks and forts ashore. The Danish position was further protected by a number of sandbanks that effectively meant the British could not bring their largest (and deepest) warships within range of the Danish lines. The British were forced to depend on the fighting power of their smaller line-of-battle ships under the command of Vice Admiral Lord Nelson to win the day.

Nelson’s strategy was simple. Navigating the offshore channel in line of battle, parallel to the Danish position, each British ship would anchor in turn opposite a Danish ship and engage it at close range until it either surrendered or was destroyed. Nelson transferred from his flagship to the smaller HMS Sea (76 guns) for the battle, which commenced around 10.30 am. William Bligh fought close by Nelson’s ship and was later commended by Nelson for the Glatton’s conduct. The British triumphed, and Bligh left an account of the fierce battle:1

At 10:26 the action began. At noon the action continuing very hot, ourselves much cut up – our opponent the Danish Commodore struck to us but his seconds ahead and astern still kept up a strongfire. At 11:24 our fore topmast was shot away, seven of our upper deck guns disabled by the enemy.

The action continuing very hot at 2:45 it may be said to have ended. Our losses 17 killed, 34 wounded. Mast very dangerously wounded. Rigging and sails shot to pieces. Seven upper deck guns, and two lower disabled by the enemy’s shot.

Our number of men on board, including officers were 309 so that we had 1/6 of the whole killed and disabled. All the ships and vessels to the southward of the Crown Battery struck and except one or two, was destroyed or taken. We fought at a cables length distant from our opponents.

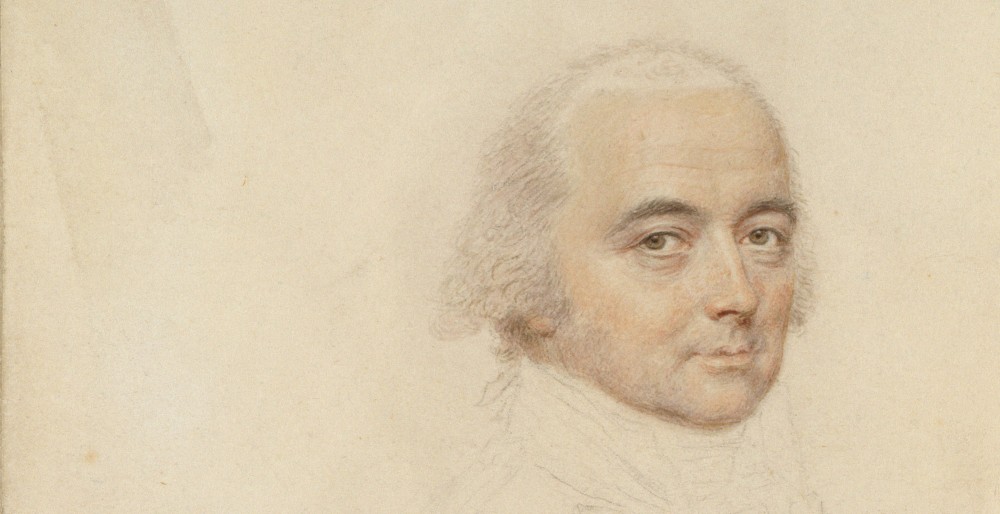

William Bligh, by John Smart, c 1797. © National Portrait Gallery, London. The sketch was probably made around 1797, shortly after Smart returned to London from India and after Bligh had successfully captured Dutch Admiral de Winter's flagship at the Battle of Camperdown. Bligh was 44 at the time.

A formidable opponent

Bligh proved to be a formidable opponent of Britain's enemies in battle, taking on larger and more heavily armed ships and relying on his men to do their duty. He was equally daunting to anyone who failed to meet his own high standards; in 1804, while commanding HMS Warrior, he unfairly accused one of his lieutenants of neglecting his duty. In response, the officer called for a court martial of his captain, stating that Bligh:2

... did publicly on the quarter deck on His Majesty's Ship Warrior grossly insult and ill treat me being in the execution of my office by calling me rascal, scoundrel and shaking his fist in my face ... and behaved himself towards me and other commissioned, warrant and petty officers in the ship in a tyrannical and oppressive and unofficerlike behaviour contrary to the rules and discipline of the Navy ...

Bligh was found guilty but only very lightly reprimanded, the court warning him 'to be in future more correct in his language.'3

In the course of the trial, Bligh attempted to justify his behaviour, telling the court:4

I candidly and without reserve avow that I am not a tame and indifferent observer of the manner in which officers placed under my orders conduct themselves in the performance of their several duties. A signal or any communication from a commanding officer has ever been to me an indication for exertion and alacrity to carry into effect the purport thereof and peradventure I may occasionally have appeared to some of those officers as unnecessarily anxious for its execution by exhibiting an action or gesture peculiar to myself to such.

Bligh’s experience in battle is just one of the many roles he fulfilled throughout his life. Be sure to visit our current exhibition, Bligh – Hero or Villain? where you can learn the full story of William Bligh’s career.

References

1 National Archives, UK, ADM/L/G/40.

2 Letter from John Frazier requesting court martial to try William Bligh, 13 November 1804, 'Minutes of the Proceedings of a Court-Martial on Captain William Bligh of HMS Warrior, held on the 25th February 1805, to investigate charges laid by Lieutenant John Frazier', Court Martial Papers, ADM 1/5368, the National Archives, Kew.

3 'Minutes of the Proceedings of a Court-Martial on Captain William Bligh of HMS Warrior, held on the 25th February 1805, to investigate charges laid by Lieutenant John Frazier', Court Martial Papers, ADM 1/5638, the National Archives, Kew.

4 Ibid, p 337.