Anchor A’wha?

An (Interim) Interpretation of an Early Nineteenth-Century Anchor Discovered at Boot Reef

In December last year, a team comprising maritime archaeologists and researchers from the Australian National Maritime Museum and the Silentworld Foundation conducted a shipwreck survey of Boot Reef, a small coral atoll in the Australian Coral Sea Territory near the northern entrance to Torres Strait. The primary focus of the survey was to locate and identify an unidentified historic shipwreck first reported in the 1890s by the captain and crew of a bêche de mer (sea slug) fishing schooner called Lancashire Lass.

According to the vessel’s captain, Sam Rowe, the crew stumbled upon an array of shipwreck material—including ‘old-fashioned’ anchors and cannons, and several thousand Spanish silver coins—while attempting to cut a channel through a coral atoll and free Lancashire Lass, which had been forced over the reef and into the atoll’s lagoon during a severe gale.

Although Rowe was intentionally vague regarding the actual whereabouts of the wreck site, a small number of Spanish coins in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (Sydney's Powerhouse Museum) are reported to have come from the hoard found by the crew of Lancashire Lass, and late nineteenth-century paperwork accompanying them state they originated from ‘Boot Reef’.

This and other historical information strongly suggested Boot Reef was the location of the mystery shipwreck, and the 2018 survey was undertaken with the goal(s) of re-locating the site and solving the riddle of its identity. The survey also aimed to find, document and—if possible—identify all other historic shipwrecks (both known and unknown) that may have occurred on the reef.

Anatomy of an atoll

Ultimately, only one shipwreck was located at Boot Reef. This was surprising, given the reef’s size (approximately 12 kilometres long), its sudden appearance from great depths (the seafloor rises precipitously from over 1,500 metres to approximately one metre depth in a span of less than half-a-kilometre), and the fact it straddles one of the most heavily-travelled entrances to Torres Strait used by mariners during the nineteenth century.

Satellite image of Boot Reef, showing the unique ‘boot’ shape for which it is named, its two narrow lagoons, and the ‘isthmus’ that separates them. Image: Geospatial Intelligence Pty Ltd/Digital Globe.

Boot Reef is actually a double atoll in that it features two narrow lagoons separated by a thin ‘isthmus’ of shallow reef flat. While relatively long, the reef is admittedly only a few kilometres wide at its widest point, and surrounded on all sides by very deep, navigable water. It is a relative speck in the vast expanse of the ocean, and a sailing vessel unintentionally striking such a small area is the shipwreck equivalent of making a tragic and unbelievably unlucky hole in one.

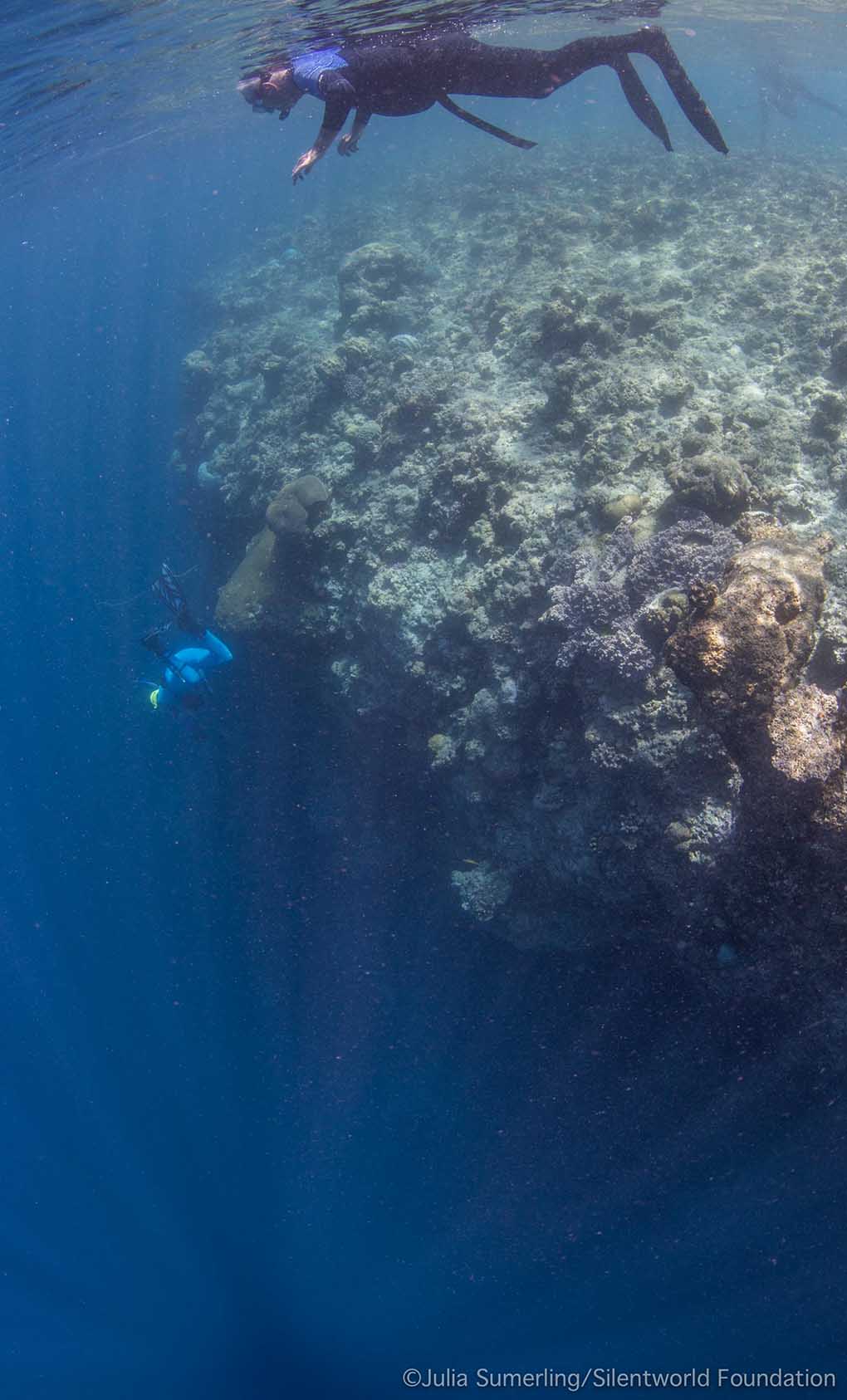

The seafloor at Boot Reef rises rapidly from over 1,500 metres to approximately one metre depth. In some places—such as this wall along the western side of the ‘isthmus’—the reef literally drops away vertically into the abyss. Image: Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation.

The reef’s unique geography also proved somewhat challenging for the team, as it is an environmentally dynamic area that is often exposed to the full brunt of the sea’s fury (luckily, the weather proved favourable for most of the expedition, and the sea state over much of the reef during this period was relatively calm). A wooden-hulled vessel grounded within its shallow, rocky confines would have been all but obliterated within a very short span of time.

Weather conditions at Boot Reef can generate massive seas that would make short work of a stranded wooden vessel. The waves shown in this image occurred during the expedition and reached heights of between three and four metres. Image: Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation.

Scattering artefacts

In the case of the shipwreck at Boot Reef, this is exactly what happened. The hull’s timber components were largely—if not completely—destroyed by wind, tidal and wave action. What little remained fell victim to the ravenous appetites of micro- and macroscopic marine organisms. The same fate befell cargo, personal effects and other artefacts made from organic material such as timber, leather, bone and fabric. Only objects made of more robust inorganic material—such as ceramic and glass, and metals like iron, lead and copper and its alloys—survived.

Smaller, more delicate artefacts were scattered across the reef flat and deposited, in whole or in part, in small nooks and crannies among the rock and coral, while larger objects representing the vessel’s architecture and fittings remained exposed on the reef top. Over time, those made of iron reacted with the surrounding seawater and were overgrown by a dense matrix of concrete-like corrosion product and colonising sea life.

This run of anchor chain was the first indication an historic shipwreck had been discovered at Boot Reef. Image: Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation.

One of these iron artefacts was a run of historic anchor chain that stretched nearly 200 metres across a section of Boot Reef. It was detected almost simultaneously by a magnetometer towed behind the project’s survey vessel Maggie III, and team members investigating a suspiciously dark patch of reef that showed signs of a biological phenomenon known as ‘black reef’.

In the wake of the chain’s discovery, the team isolated its search to the immediate surrounding area, and in relatively short order made additional discoveries—foremost among them a large, historic ship’s anchor lying flat on the reef top a short distance from one of the chain’s ends.

The author (right) and Irini Malliaros from the Silentworld Foundation use ‘old school’ methods to obtain measurements of the Admiralty Old Pattern Long-Shanked Anchor found in the shallows at Boot Reef. Image: Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation.

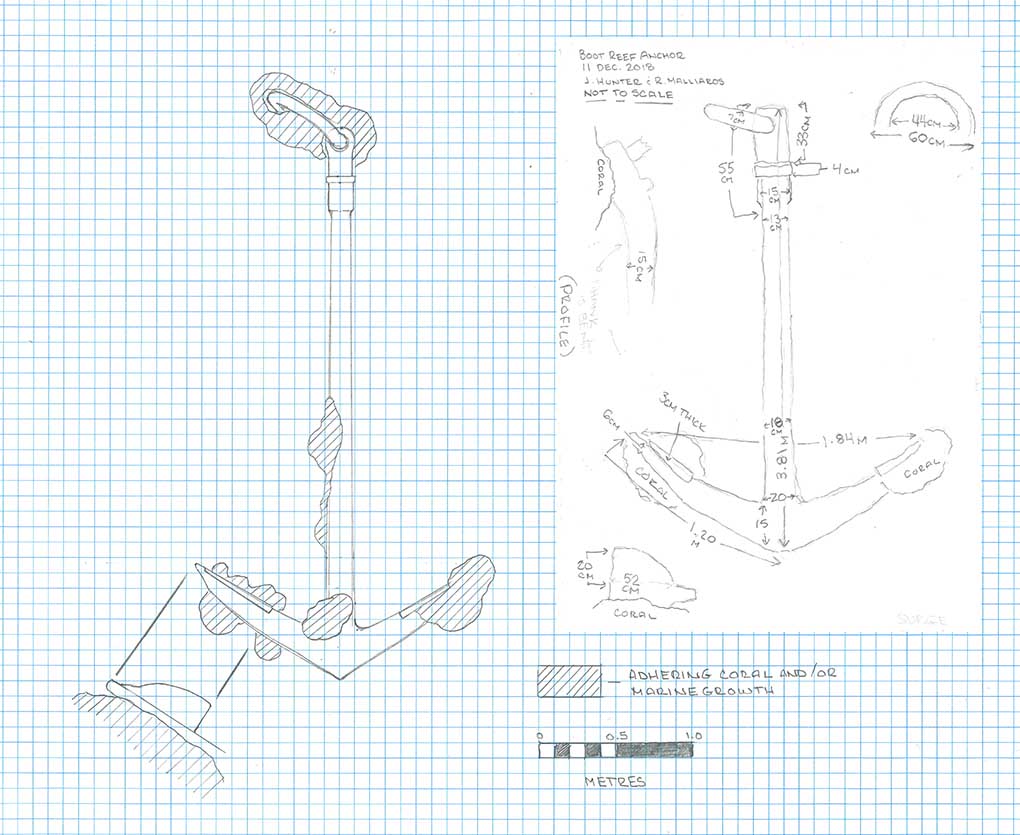

As historic anchors go, this one was a doozy: It measured nearly four metres in length, and the distance between its bills (the pointed tips of each of its triangular palms or ‘flukes’) was almost two metres. The palms themselves were over 50 centimetres long and 40 centimetres wide. The most striking thing about the anchor, however, was its form. Characterised by a thin, somewhat spindly shank that terminated in a large iron ring at one end, and a pointy, triangular crown formed by the confluence of its two arms at the other, the anchor exhibited all the traits of a wooden-stocked ‘Admiralty Old Pattern Long-Shanked’ variant.

A scaled drawing of the anchor (left) derived from measurements and a field sketch (inset) produced by the author. Image: James Hunter/Australian National Maritime Museum

Anchoring the detail

Admiralty Old Pattern Long-Shanked anchors are unique in Australia because they tend to be associated with some of the nation’s earliest historic shipwrecks. First developed for the British Royal Navy during the latter half of the eighteenth century, the Old Pattern Long-Shanked design remained in vogue until the first few decades of the nineteenth century, when it was gradually replaced by ‘improved’ versions of the Admiralty-Pattern anchor. These newer variants featured an array of modifications, including shorter, more robust shanks, iron stocks, and curved arms typical of the classic fouled anchor motif found on sailor tattoos and other modern nautical iconography. The presence of a wooden-stocked Admiralty Old Pattern Long-Shanked anchor at Boot Reef provided compelling evidence that the shipwreck was of an earlier vintage—likely that of a vessel lost prior to 1830.

A number of unique attributes, such as a pointed crown and spindly shank, identified the anchor as an Old Pattern Long-Shanked variant. The author is shown sketching some of these features. Image: Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation.

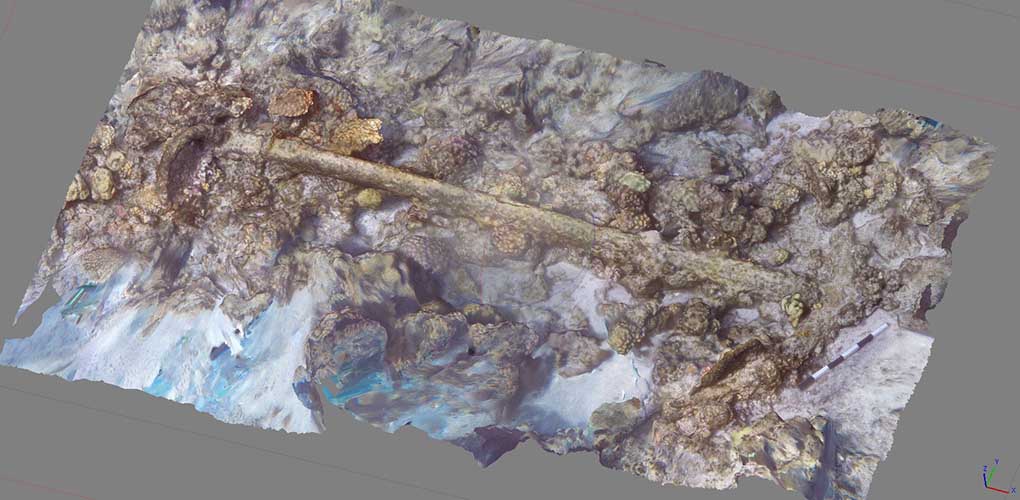

The anchor was left where it was found; consequently, the team documented it in place as thoroughly as possible via a combination of high- and low-tech methods. In addition to acquiring measurements by hand (with folding rulers and reel tapes), team members documented the anchor extensively with still photography, video, and 3D photogrammetry. The latter technique resulted in a detailed digital model that will be used in conjunction with historical information to expand our understanding of the anchor, including its possible origin, method of manufacture, weight and use aboard ship.

Low-resolution digital model of the Boot Reef anchor produced from 3D photogrammetric data.

Already, the anchor has started to reveal details of the catastrophe that deposited it on the reef top. Examination of the shank near the ring revealed it has been bent and twisted—a testament to the tremendous forces exerted on the anchor (and the vessel to which it belonged) during the wrecking event. Ultimately, these and other details collected from the anchor will inform the overall study of the shipwreck site, and contribute to the team’s ongoing effort to establish its identity.

A 3D model of the anchor (shown here in a screen capture) was generated from hundreds of digital still images, and is one of the many forms of data collected from the shipwreck site that will be used to interpret and share its story. Image: James Hunter/ANMM/Silentworld Foundation.