Earlier this year I flew to England a examine a previously unknown log of HMS Sirius, written by First Lieutenant William Bradley, covering the period from the departure of the First Fleet from Portsmouth, UK, in May 1787 to the return of the ship’s crew to England in April 1792 aboard the Dutch vessel Waakzaamheydt.

It was a formative period in Australia’s colonial history and the logbook, signed by William Bradley, written in his neat hand and illustrated with maps and small coastal profiles, is an extraordinary gift to the nation.

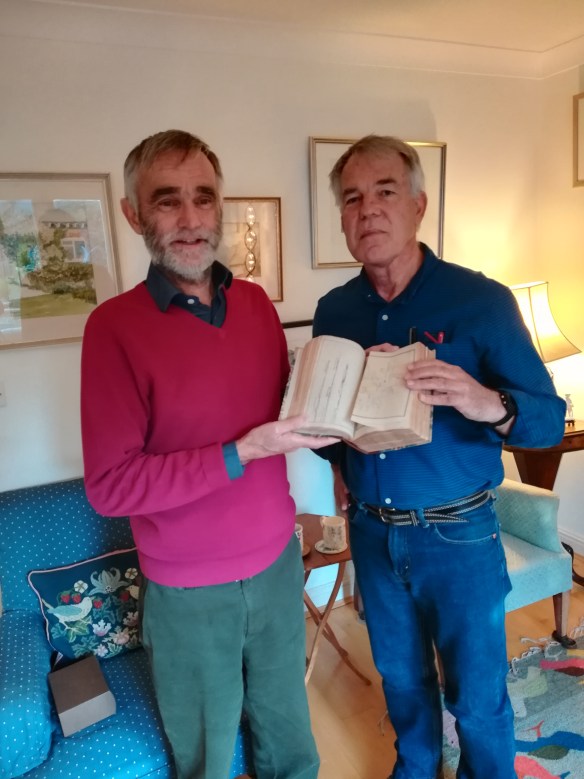

The donor of the logbook, Mr Anthony Gannon, presenting it to Dr Nigel Erskine. The book was passed down through Mr Gannon’s maternal grandfather. Image courtesy Nigel Erskine/ANMM.

The log has been donated to the museum by UK resident Mr Anthony Gannon. It had previously passed down through several generations of his family, including Vice-Admirals Harry Edmund Edgell CB and Sir John Augustine Edgell KBE CB FRS, Hydrographer of the Navy (1932–1945). The latter was Mr Gannon’s maternal grandfather.

Mr Gannon’s ancestor Henry Folkes Edgell was captain of the 14-gun sloop HMS Pluto, which served off the east coast of North American (the Newfoundland Station) at the same time that William Bradley was captain of HMS Cambrian on the same station. HMS Pluto was a sister ship to HMS Comet, Bradley’s first command, and it is possible that the log came into the Edgell family through this connection.

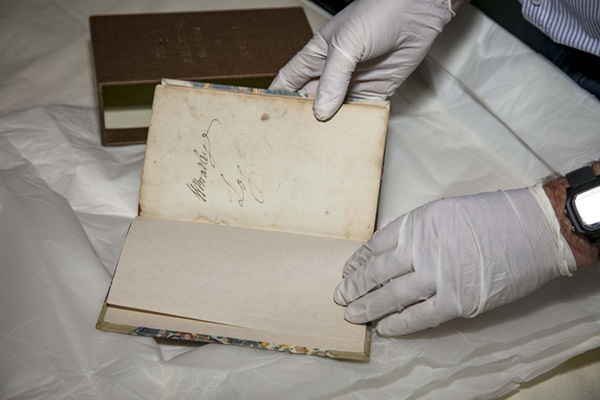

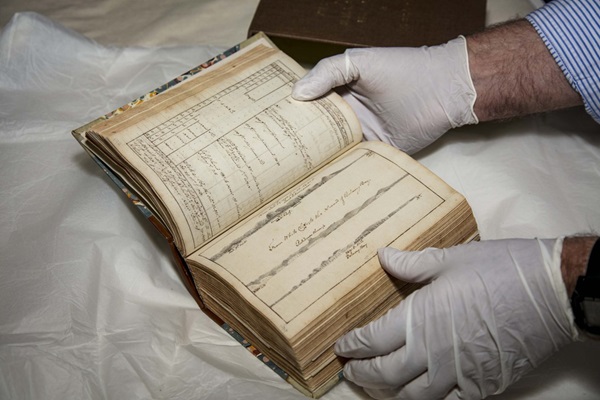

William Bradley’s log arrives at the Australian National Maritime Museum. Image: Andrew Frolows/ANMM.

William Bradley’s log

Much of what we know about William Bradley is based on his journal in the Mitchell Library. Like the journal, William Bradley’s log is a ‘fair copy’ made at some time after the events it describes.

The two works complement each other, the journal providing a flowing description, while the log is a precise record of Sirius’ course, speed and position, weather conditions, wind direction and matters relating to sailing the ship, with additional remarks about anchorages or uncharted dangers encountered during the voyages of the Sirius and subsequently the Supply and Waakzaamheydt.

Among the entries are some surprising details, such as the following, which refers to Sirius’ battle to round southern Tasmania on 22 April 1789 while returning to Port Jackson from the Cape of Good Hope:

AM. At 2 weathered the land to the eastward at 1½ or 2 miles distant; from the land trending away N [north] we knew this to be Tasman Head and the point of land we were at 7 AM, the South Cape. The ship was so pressed with sail to get her round the land that the pumps were kept going all night and all hands upon deck. The sea washed away the figurehead.

Two days later the damage to the ship’s stem was so serious that the jib boom and spritsail yard had to be removed, and the bowsprit was jury-rigged with ropes to each cathead. Little wonder that when the ship finally arrived safely back at Port Jackson it needed major repairs to strengthen the hull, before it was again ready for sea.

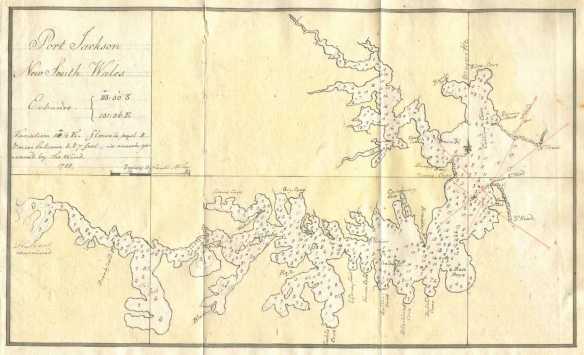

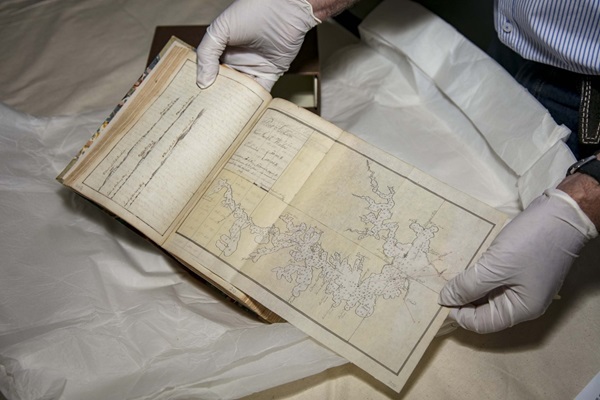

The place where those repairs were made is named Careening Cove on Bradley’s chart of Port Jackson inserted in the log (pictured below).

Bradley surveyed the harbour under Captain John Hunter, who sent a large and beautifully coloured version of the chart back to England, where it can now be seen at the National Archives in Kew.

Compared with the chart in Bradley’s log, it is clearly a more accurate version, and as intended, became the basis for the first published chart of the harbour. A wonderful aspect of Bradley’s chart of the harbour in his log, however, is his inclusion of names given to many of the bays and headlands.

The chart of Sydney Harbour in Bradley’s log notes place names, some of which are still in use, while others have been superseded. ANMM Collection.

Some of these, such as Sydney Cove, Rose Bay, Farm Cove, Hunter Bay and Bradley’s Point, are still used today, but Bradley’s chart includes other names that haven’t survived. Keltie Cove (Double Bay), Waterhouse Point (Woolwich) and Collins Cove (North Harbour) refer to James Keltie, Master of the Sirius; Henry Waterhouse, a midshipman on the Sirius; and David Collins, Deputy Judge Advocate of the colony. Bloody Point (Dobroyd Point, Iron Cove) probably refers to the murder of two convicts.

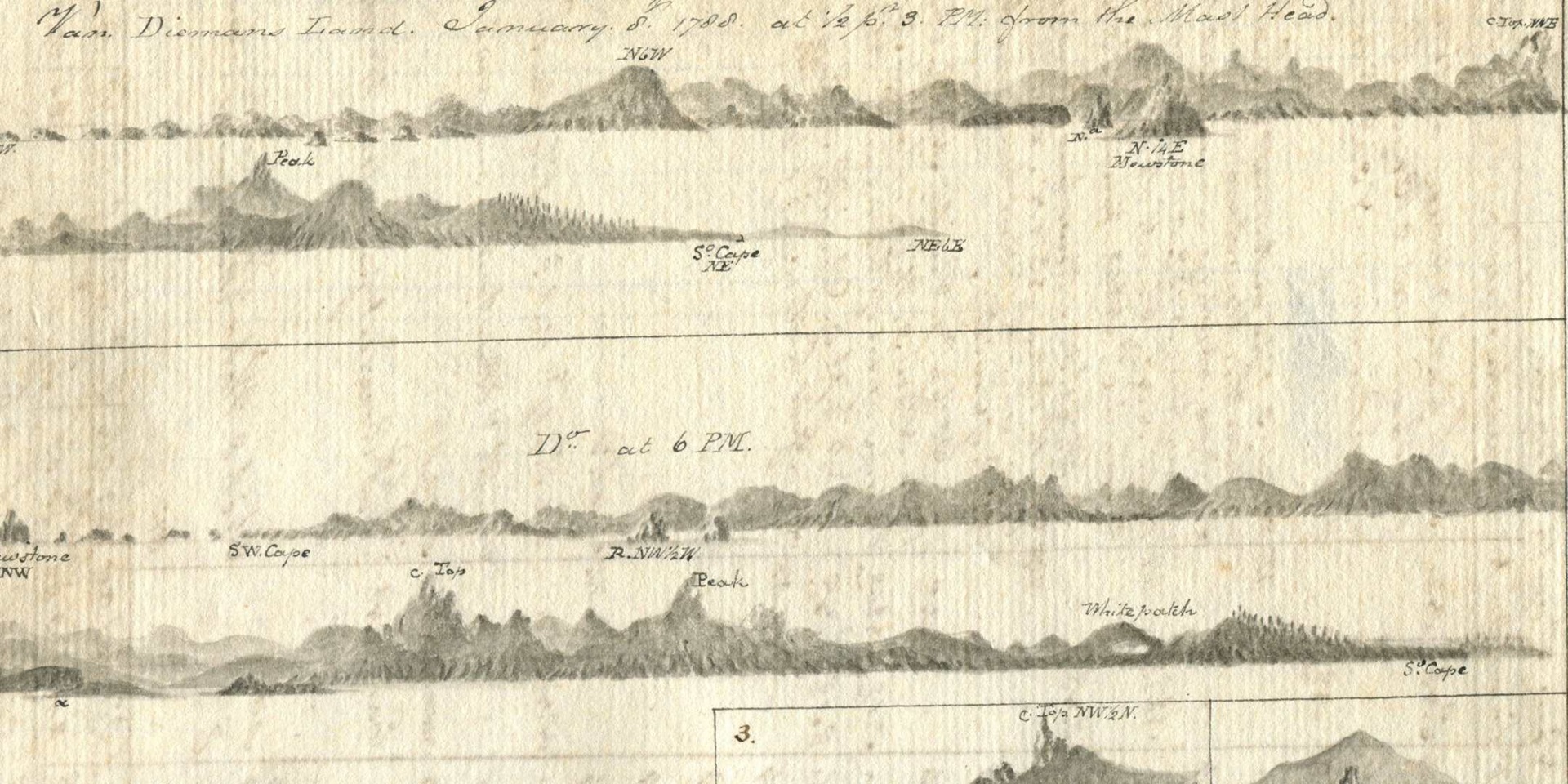

In addition to Port Jackson, Bradley’s log includes charts of Botany Bay, Rio de Janeiro and Table Bay (Cape of Good Hope), as well as the Waakzaamheydt’s route and anchorages on the voyage to England. Additionally the log includes exquisite coastal profiles of the Canary Islands, Rio de Janeiro, the coast of southern Tasmania (Van Diemen’s Land) and the entrances to Botany Bay and Port Jackson – these last being the earliest depictions of the coastal cliffs around Sydney yet discovered.

William Bradley’s career

Many details of William Bradley’s life remain a mystery, but the basic details of his naval service are clear.

After returning to England in April 1792 he was promoted Commander and placed in charge of the 14 gun Comet, seeing action in the Battle of Ushant off the coast of France. Following that battle he was promoted Captain to the 74-gun ship Ajax (1794–1802) and subsequently commanded the 40-gun Cambrian on the Newfoundland Station (1802–1805). He returned to England in 1805 and was appointed Captain of the 74-gun Plantagenet as part of the Channel Fleet until 1809, when he departed the ship.

The exact details of his departure remain unclear, but in January 1809 Bradley informed the Admiralty that he had received a writ to appear before His Majesty’s Court of Common Pleas. Bradley attributed the writ to a sentence passed by a court martial, of which he was president, upon Captain Christopher Laroche of the 38-gun frigate HMS Uranie [Urania].

At this court martial, convened at Portsmouth in July 1807, Laroche was charged with failing to do his utmost to bring about an engagement with an enemy frigate. Found guilty, he was dismissed from his command.

While the exact nature of the writ brought against William Bradley is unknown, it effectively brought an end to his sea-going career. After taking an extended leave of absence to attend the court in London, and with the stress of the situation weighing on him heavily, Bradley’s health declined to a point where he was forced to relinquish command of the Plantagenet. However, by the following year he had been appointed to the shore-based Impress Service at Cowes on the Isle of Wight.

Finding men to crew the ships of the Royal Navy during the long war with France and its allies was a constant problem. While the government attempted to attract volunteers by offering the ‘King’s bounty’ (an inducement equivalent to about two month’s advance wages) to men who freely entered the service, in times of need it was also empowered to take British seamen from merchant ships in home waters and to round up suitable men on shore through the press gang, and force them into naval service.

By their nature, the activities of the Impress Service were unpopular and its members regularly liable to verbal or even physical abuse. Bradley’s career was rocked in 1812 by an anonymous letter sent to the Admiralty – whether made in retribution, a genuine observation, or simply a mistake – claiming that he had been seen intoxicated in the street at Cowes. The complaint came at a critical moment in Bradley’s career.

By 1812 Bradley was a post captain of 18 years. Having advanced in seniority to the top of the list of captains serving in the navy, he could expect, by convention, to be promoted to the rank of admiral when the next vacancy occurred. In 1812 there were 191 flag officers on active service and another 31 ‘superannuated’ rear-admirals. In effect, a superannuated officer was a retired officer holding honorary rank but receiving a pension equal to the half pay of a rear-admiral.

Bradley seems to have first become aware of the threat to his expected promotion when a panel of three captains was tasked with investigating the complaint against him, and he quickly went about securing character references that he sent to the Admiralty Board. At this stage, the seven-member board appears to have been against awarding Bradley his flag, but after Bradley successfully appealed directly to the Prince Regent, it reversed its earlier decision, placing him on the list of superannuated rear-admirals on 22 September 1812.

The victory should have been enough to support Bradley, his wife, Sarah and their children in relative comfort, but events were soon to prove otherwise.

In 1814 William Bradley was found guilty of defrauding the postal system as outlined in The Salisbury and Winchester Journal on 25 July:

It appeared on the trial that Admiral Bradley carried to the post-office, at Gosport, a parcel containing 411 letters, which he pretended to have brought by the vessel William and Jane, from Lisbon, upon which he claimed (in the name of Wm. Johnstone) and obtained a premium of 2d. per letter (amounting to about £3:8 s) which is given by a statute of George II to masters of vessels bringing letters from foreign parts. The letters were all written in his own hand on half sheets of paper, and addressed to different Members of Parliament. He had previously obtained premiums at the same post-office for the delivery of great numbers of letters under exactly similar circumstances, and suspicion of fraud was first entertained at the general post-office in London, by order of which enquiry was set on foot at Gosport.

… Evidence was given on the prisoner’s behalf, of his intellects having been in a disordered state in the year 1809; testimony to the honesty of his character was also adduced; the Jury however, returned a verdict of Guilty.

A singular circumstance is related respecting the above prisoner; it is positively asserted that he incurred an expense of £2 for the chaise hire, to carry the letters to Gosport; which expense, with the cost of the materials of 411 letters, must have reduced his gain to almost nothing.

In October, the same newspaper announced that Bradley was to be transported for life, but within weeks he received a pardon on condition that he leave Britain and never return. As a result, William Bradley crossed the Channel to France where he lived at Le Havre until his death in March 1833.

The circumstances of Bradley’s fraud suggest a mental breakdown which, as his defence argued, may have been linked to incidents in 1809. Whatever the reason, it was a sad end to a long and dutiful career.

With the log now finally in Sydney, museum Director Kevin Sumption commented, ‘This is, without doubt, the most significant early colonial acquisition made in my time and I dare say one of the most significant documents ever donated to an Australian cultural institution. We are indeed privileged to be entrusted with this national treasure.’

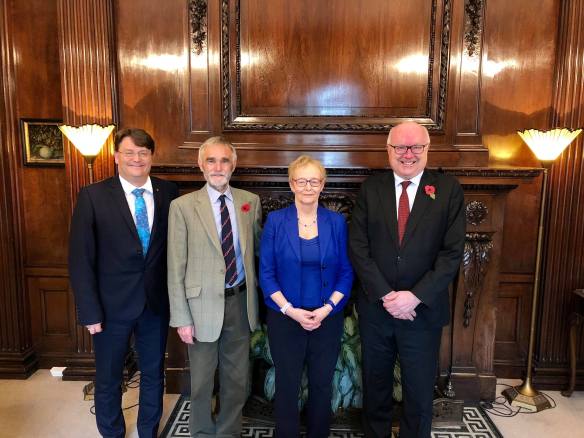

With the log now finally in Sydney, museum Director Kevin Sumption commented, ‘This is, without doubt, the most significant early colonial acquisition made in my time and I dare say one of the most significant documents ever donated to an Australian cultural institution….’ From Left: Kevin Sumption PSM, Mr Anthony Gannon and Alexina Gannon with The Honourable George Brandis QC, at Australia House in London (November 2018). Image: Australian High Commission, Australia House, London.

— Nigel Erskine, Head of Research.