The spiritualist movement of the late 19th century believed life and death included an in between realm where spirits were able to exist and communicate with the living. In the case of the missing Browne brothers, their family believed the brother’s spirits could provide some startlingly detailed information about their deaths. Images: National Library of Australia.

Communing with the dead

In tasteful parlour rooms across the world, the mood was set. Accompanied by soft lighting and gentle music, people quietly gathered, waiting not for romance but in the hope of receiving messages from the dead. The appearance of a well-known historical figure would cause a stir but generally, it was messages from loved ones who had passed on which audiences waited breathlessly for.

The spiritualist movement of the late 19th century believed life and death included an in between realm where spirits were able to exist and communicate with the living. In the case of the missing Browne brothers, their family believed the brother’s spirits could provide some startlingly detailed information about their deaths.

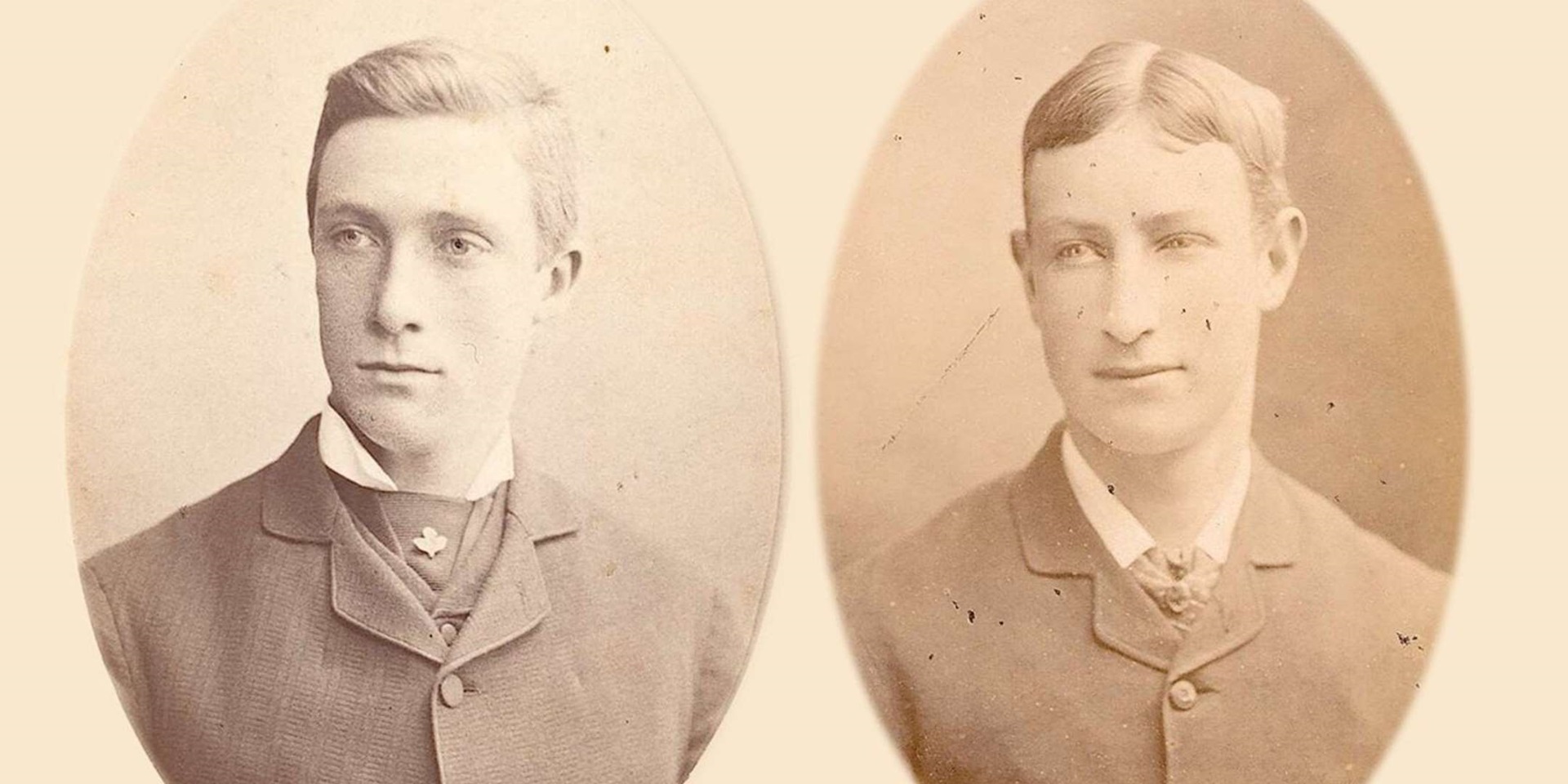

A possible portrait of elder son Hugh Browne, who was lost with his brother Will in 1884. Image: National Library of Australia, via Trove.

Will and Hugh didn’t return home

In December 1884, three young men went sailing on Port Phillip Bay in their newly purchased yacht lolanthe. Leaving home on Saturday evening, the trio planned to spend the evening fishing, then head to Frankston on Sunday before finally returning home the following Monday morning.

Two of the men, 18-year-old William and 20-year-old Hugh, were the sons of Hugh Junor Browne. Mr Browne had owned a successful distillery on the Yarra River but was now retired and spent much of his time pursuing his primary interest: spiritualism. Despite their mother’s ardent protests (she later admitted to being much more ‘intuitional’ than her husband), the boys left that night… and did not return on Monday.

Trove.'>

Trove.'>Portrait of William Browne. Will’s body washed ashore a week after he and his brother went missing. Image: National Library of Australia, via Trove.

The ‘medical clairvoyant’

By Tuesday Mrs Browne, now in a state of extreme anxiety and called the ‘medical clairvoyant’ George Spriggs for answers. Spriggs was known for his ability to diagnose and treat diseases or ailments while in a trance. His practice was to not ask the patient any questions before entering his trance state, as he believed the spirit world would provide him with all the details he sought.

On his arrival at the distraught Browne house, Spriggs quickly slipped into a trance and loudly proclaimed ‘Oh! I perceive it is all about the sea.’ Supposedly without any further information from the older Brownes, Spriggs revealed the terrible fate of the brothers.

It was a detailed account, going so far as knowing the accident had occurred at ‘9 o’clock on the Monday morning through, the jib-halyard fouling in a squall as they were putting the yacht about on another tack.’ He finished his tale stating that lolanthe would never be recovered as it had gone down in deep water.

The Browne family reached out to ‘medical clairvoyant’ George Spriggs to assist their search for Will and Hugh. A rational faith, or, A scientific basis for belief in a future progressive state versus faith in traditions and dogmas irreconcilable with reason … / by Hugh Junor Browne via Trove.

Searching with a séance

The government steamer Dispatch was sent to Port Phillip Bay to search for Iolanthe but found no trace. Spriggs was still on the case and later joined the Browne family in a séance, during which both Hugh and Will appeared to their parents.

lolanthe in Port Phillip Bay, 1884. Images: National Library of Australia via Trove, Mr Hugh Junor Browne and his sons & Mrs Elizabeth Browne with her four daughters Pattie, Lilian, Nellie and Alice.'>

lolanthe in Port Phillip Bay, 1884. Images: National Library of Australia via Trove, Mr Hugh Junor Browne and his sons & Mrs Elizabeth Browne with her four daughters Pattie, Lilian, Nellie and Alice.'>The Browne family were part of the Spiritualism movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They engaged the methods of the ‘medical clairvoyant’ George Spriggs in the search for their two sons, Will and Hugh. Images: National Library of Australia via Trove, Mr Hugh Junor Browne and his sons & Mrs Elizabeth Browne with her four daughters Pattie, Lilian, Nellie and Alice.

Mr Browne wrote that the boy’s first words were apologies to their mother, whose forewarning had run through their heads as they struggled in the water.

The clairvoyant stated that the brothers appeared in good health during his communication with them. Spriggs confirmed that Will and Hugh still ‘lived’ and loved their parents. But appearances can be deceiving in the spirit world: a week later the body of Will was found washed up on the beach at Brighton. His body was in a highly decomposed state and missing the left arm.

Evidence

At the inquest into Will’s death, Mr Browne was asked to testify about the events preceding his son’s departure. He attempted to convince the coroner to listen to the account of the accident as given by George Spriggs, but the coroner ‘declined to receive that kind of evidence’.

It was concluded that a shark had bitten Will’s arm but the cause of his death was drowning. The funeral was held that same day, with no mourning coaches or burial service. His father gave the eulogy, calm and dry-eyed in the ‘glorious knowledge’ that his sons were now so happy, that even if they could come back, they would choose not to.

Geelong Advertiser (Vic. : 1859 - 1929) 24 December 1884: 3, viaTrove.'>

Geelong Advertiser (Vic. : 1859 - 1929) 24 December 1884: 3, viaTrove.'>During the inquest into Will’s death, the coroner declined to accept any ‘evidence’ from George Spriggs. Geelong Advertiser (Vic. : 1859 – 1929) 24 December 1884: 3, via Trove.

Two weeks later a four-metre great white shark was caught at Frankston Pier with a mouth so large ‘a man could dive clean down its throat’. As was customary, and to the excitement of paying spectators, the shark’s stomach was cut open. The Age newspaper reported that inside were ‘portions of a coat, vest and trousers and in one of the vest pockets were found a gold watch and a silver chain, and in the trousers pocket the sum of 10s in silver, two keys and a pipe…and a human arm’.

These possessions and the arm were not Will’s but actually belonged to his older brother Hugh.

Two weeks after the disappearance of Will and Hugh Browne, a large shark was caught off Frankston Pier. Its stomach contents were presumed to link the shark to Browne men. The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954) 29 December 1884: 5, via Trove.

Mr Browne still took the news solemnly. He did not see it a form of closure, but rather as confirming the details he had received directly from Will and Hugh during a séance, where they had talked of a ‘large fish’. Hugh’s recovered watch had stopped at 9 o’clock, the exact time George Spriggs said the lolanthe had sunk.

An engraving published in the Australasian Sketcher, 14 January 1885. On the reverse, an accompanying article gives an account of the yachting accident and subsequent death of Hugh and William Browne. ANMM Collection 00006063.

00006063.'>

00006063.'>The verso of an engraving published in the Australasian Sketcher, 14 January 1885, titled ‘Devoured by a shark: sketch of the shark’. This article (in the third column) gives an account of the yachting accident and subsequent death of Hugh and William Browne. ANMM Collection 00006063.

A spiritual family

As sceptical we may be of these days of communing with spirits, spiritualism was popular at the time and, although the coroner may not have had time for such evidence, being a spiritualist was not seen as something to hide. Mr Browne’s eldest daughter was considered an automatic writing medium, who was believed to be able to scribe in any language or style whilst being seemingly unaware of what she was writing.

One of Browne’s other daughters, Elizabeth ‘Pattie’ Browne, married Sir Alfred Deakin, who would go on to become Australis’s first Attorney-General and the second Prime Minister. Deakin himself was a keen spiritualist in his younger years and had met Pattie through the movement. He was the President of the Victorian Spiritualist Association and wrote extensively on his beliefs.

Elizabeth ‘Pattie’ Browne and her husband, Sir Alfred Deakin, were both involved in the Spiritualism movement. Image: National Library of Australia.

On the eve of the inquest into Will’s death, Pattie and Alfred Deakin boarded a ship to San Francisco. Pattie wrote that she spent most of that trip in their cabin, grieving for her lost brothers and being terribly seasick.

In 1920 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, visited Australia. Doyle was a dedicated spiritualist himself and took a particular interest in the case of William and Hugh Browne. He wrote about them in his book The Wanderings of a Spiritualist.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Doyle was a dedicated spiritualist himself and took a particular interest in the case of William and Hugh Browne. Doyle felt that the tale ‘should have converted the city as surely as if an angel had walked down Collins Street’. Image: Toronto Public Library.

Doyle was deeply impressed with the story, particularly in the happiness the brothers had apparently found and the gratitude they had towards their father for opening their minds to spiritualism. The only problem that confounded Doyle with this tale was that it ‘should have converted the city as surely as if an angel had walked down Collins Street’.

Closure for Mrs Browne

The tale of the Browne boys and their crew mate passed into the annuals of history. The shark was displayed at Hall’s stables in Swanston Street for a day, and once the excitement died down, it too was forgotten. But spiritualists who continued to read Mr Browne’s writings were heartened, probably none more so than Mrs Browne. Her son’s apparitions continued to make special mention of her, reassuring her that they felt no pain, were content and still apologising for not listening to their mother’s intuition.

— Myffanwy Bryant, Curatorial Assistant

The first week of September is history week and the theme for 2018 is ‘Life and Death’. Join the Museum’s own ‘pirate band’ The Mutineers as well as the renowned sea shanty singers 40 Degrees South for a night of songs about life and death at sea.