Old Man’s Hat, where the 1940 inscription marking the detention of Pierre Loti was carved, offers spectacular views over South Head, the Tasman Sea and hundreds of historic inscriptions left by sailors, passengers and Sydney residents. Image: Ursula K Frederick, Sydney Harbour National Park.

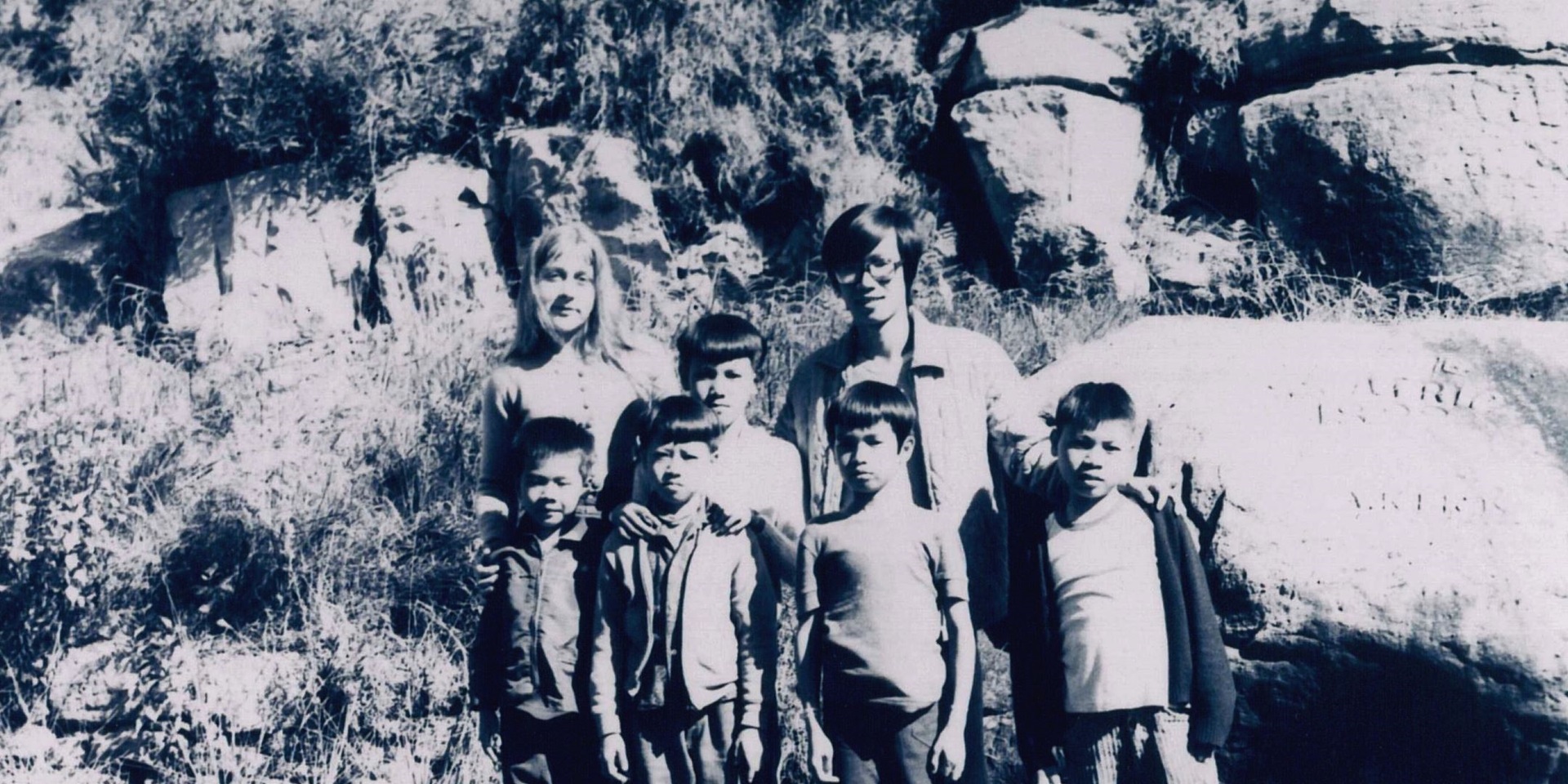

Saigon bristled with terror in April 1975. As shelling and small-arms fire sounded out an ever-shrinking cordon around the South Vietnamese capital, wails of a different kind split the airspace above the city. On board a Royal Australian Air Force Hercules aircraft, over 200 traumatised children and infants – primarily orphans – were being tended by nurses, doctors and military personnel. Leaving Ton Son Nhat airport on 3 April, these bewildered passengers were then transferred to a Qantas flight bound for Sydney. Numbering among the 2500 children scooped up by ‘Operation Babylift’, they arrived at North Head Quarantine Station just weeks ahead of the final collapse of South Vietnam.

Oddly enough, the Babylift children were not the first displaced Vietnamese to be held at North Head. It would be another year before the earliest refugee boats – the vanguard of a rickety flotilla escaping the humanitarian crisis afflicting Southeast Asia – landed on northern Australian shores. Although two small groups of these arrivals were briefly accommodated at Sydney’s Quarantine Station in 1977, in April 1975 only the Babylift evacuees were being tended by nurses and community volunteers at this hilly headland near Manly.

As their homeland dissolved into chaos, carnage and political persecution, these small survivors faced an alien land, an unfamiliar language and an unexpected maritime tradition. Whether sitting on the beach or playing with donated toys, the children were surrounded by a seemingly endless gallery of messages carved into North Head’s sandstone by sailors, passengers and visitors once held in quarantine. Stretching back to 1835, this practice extended across many languages including French, Italian, Finnish and Russian, alongside Arabic, Indonesian, Japanese and Chinese. But, far from the comfort of the Quarantine Station’s airy dormitories and the gentle waves washing the beach at Spring Cove, a unique rock carving hinted at another invasion in Vietnam’s fractured past.

There are over 1600 carved and painted inscriptions at North Head Quarantine Station, including these messages marking British immigrant ships of the nineteenth century and Dutch trading vessels from the twentieth century. Image: Ursula K Frederick, Sydney Harbour National Park.

French Indochina in the sandstone

Facing out over the Tasman Sea is Old Man’s Hat, an outcrop of North Head exposed to the high winds and booming waves a hundred metres below. On a large flat rock, half-hidden under Eastern Suburbs banksia scrub, bold deep letters spell out:

THUAM

l’INDOCHINE

6 10 40

This large inscription left by a ‘Tonkinese’ sailor in 1940 marks the beginning of a long detention for Vietnamese and Arabic crewmen aboard the French steamship Pierre Loti. Image: Ursula K Frederick, Sydney Harbour National Park.

Inscribed over a year before the attacks on Pearl Harbor and Malaya, this long-neglected memento instead forms a direct maritime link to the Japanese occupation of French Indochina. It was carved by one of the Vietnamese sailors aboard the Messageries Maritimes steamship, Pierre Loti. This ageing twin-screw passenger vessel had departed Saigon in September 1940 as Japanese troops infiltrated the northern province of French Indochina. Politically and militarily weakened by the surrender of their homeland on 22 June, French resistance to this occupation was minimal. Nevertheless, after negotiating an uneasy peace, the Japanese did not press on into the southern Indochinese territories – including Saigon – until July 1941. Five months later, on 10 December, Japanese aircraft based in Saigon sank and attacked the British battlecruiser HMS Repulse and the battleship HMS Prince of Wales at the outset of the Pacific War.

In the meantime, the fate of Pierre Loti’s crew demonstrated the global political complexities facing French officers and colonial sailors after the fall of France.

The seventieth anniversary of Henri Sautot’s declaration that New Caledonia would henceforth fall under Free French rather than Vichy rule was celebrated by this 2010 stamp. Image: L’Office des Postes et Télécommunications de la Nouvelle-Calédonie.

From Saigon, Pierre Loti headed for New Caledonia, where engine difficulties detained it in Noumea harbour. Its arrival, however, coincided with the tense landing of a new French governor. Voyaging from the New Hebrides on the Norwegian ship Norden – and escorted by the Australian cruiser HMAS Adelaide – Henri Sautot came ashore on 19 September and immediately issued a proclamation. Although his predecessor had favoured allegiance to the collaborationist Vichy government in France, Sautot declared that both the New Hebrides and New Caledonia were now loyal to the Free French forces led in exile by General Charles de Gaulle.

HMAS Adelaide escorted the new Free French governor, Henri Sautot, to New Caledonia in September 1940. Image: Australian National Maritime Museum, ANMM Collection 00021114.

If Sautot’s coup d’etat coincided with the wishes of many local residents, military opinion was far more mixed. Given the deadly British naval bombardment of the Vichy fleet at Mers-el-Kébir in Algeria on 3 July, both the artillery units ashore and sailors aboard the aviso (sloop) Dumont d’Urville remained uncertain whether to accommodate or open fire upon Adelaide. In the end peace prevailed, although just days later the Vichyist Dumont d’Urville weighed anchor for Saigon.

After its occupation in July 1941, Saigon remained under mixed Japanese and French control until the conclusion of the Pacific War in September 1945, when this aerial photograph was taken. Image: Australian War Memorial, P031 32.009.

Sentiments were similarly diverse aboard Pierre Loti. On 8 October the vessel departed Noumea carrying over 200 exiled Vichy sympathisers. The ship’s officers and crew – including both indigenous Vietnamese (or ‘Tonkinese’) and Arab (‘lascar’) sailors – were equally equivocal about their loyalties. Nominally bound for Indochina, the ship called first at Brisbane and then, on 17 October, sailed into Sydney Harbour.

No stranger to Sydney

Pierre Loti was hardly a stranger: Since 1937 the French ship had maintained a roughly monthly service between Sydney and Noumea, sometimes connecting to Saigon or the northern Indochinese port of Haiphong. This time, however, a different reception awaited. Alarmed by ever-escalating losses to German and Italian air and naval units – especially U-boats – the British government sought to commandeer Pierre Loti to bolster its merchant fleet. Urgent exchanges ensued between the Australian War Cabinet, the Chief of the Naval Staff, Admiral Ragnar Colvin, the French-speaking lawyer appointed as Australia’s Official Representative to Noumea, Bertram Ballard, and Sautot. By 29 October all parties had agreed to an extended detention of Pierre Loti in Sydney, pending formal requisitioning.

Pierre Loti was originally built in Scotland in 1913, passing through Russian and German owners before entering Messageries Maritimes service in 1922. Image: Jean-Paul Fontanon.

This was not the first time Pierre Loti had been seized in wartime. Launched on the Clyde in 1913, the ship was originally built as Imperator Nikolai I by John Brown & Co. Owned initially by the Russian Steam Navigation Company, it was commandeered by the Russian Navy in the revolutionary year of 1917, serving as the seaplane tender Avjator. Captured from the Bolsheviks by German forces in May 1918, it was laid up with the Armistice that November, eventually passing into French government service. Only in 1922 did the 5114-ton vessel join the Messageries Maritimes fleet as Pierre Loti, honouring the pen-name of colourful French sailor Louis Marie-Julien Viaud. From 1879 until his death in 1923, Loti’s memoir-driven novels attracted both popular and critical acclaim, particularly for their portrayal of travel, adventure and the exotic delights of colonial life.

Reflecting its pre-World War I origins, the interior of Pierre Loti was ornately decorated and spaciously laid out. The ‘Tonkinese’ crew likely served as stewards for passengers in the second-class dining area. Image: Jean-Paul Fontanon.

Seized in Sydney on 5 November 1940 under national security regulations, Pierre Loti retained its name but joined the British register. With de Gaulle’s assent, it was intended that the vessel would help maintain trade between the United States, British Empire territories and the French Pacific colonies. Alongside another commandeered Messageries Maritimes vessel, Ville d’Amiens, Pierre Loti ultimately came under command of the British Ministry of War Transport. Operated on contract by the Liverpool-based Alfred Holt & Co., it was renamed Southern Sea in 1941 but ran aground off Gabon in West Africa on 12 December 1942 and was abandoned.

Another Messageries Maritimes vessel seized for use by the British Ministry of War Transport was Ville d’Amiens, seen here in 1932. Image: Australian National Maritime Museum, ANMM Collection 00041581.

Meanwhile in Sydney, 5 November 1940 had signalled more than just Guy Fawkes Night. Fireworks of a different kind soon sparkled around the French arrivals. The Vichyist passengers deported from New Caledonia were transhipped to the Eastern & Australian Line’s Tanda, which throughout 1940 continued to trade through Asia on its regular return route to Yohohama. Leaving Sydney early in November, the Noumean deportees likely disembarked in Manila for on-passage to Saigon.

Which France?

Pierre Loti’s officers and sailors, however, vehemently protested their vessel’s seizure in Sydney. As Australian Government officials informed their British counterparts, ‘no-one on board has any real sympathy with Free France and De Gaulle [sic] … although it would be a mistake to say that they are anti-British’. Offered the opportunity of continuing their employment at British pay scales but sailing under a French flag, the crew were entreated to sign a declaration put to them in (rather poor) French:

Je desire continuer la lutte contre l’Allemange et l’Italia a m’engage a servir loyalement la cause commune de la Grande Bretagne de la France libre et de leurs allies. J’accepte donc de continuer a naviguer sur un Navire Francais [all errors are per original].

A corrected translation kindly provided by Dr Clara Sitbon suggests that the offending pledge could be rendered as:

I wish to continue the fight against Germany and Italy, and to commit myself to faithfully serve the common cause of Great Britain, Free France and its allies. I therefore agree to continue sailing on a French ship.

They refused to a man. Alarmed at the twin risks of sabotage or an attempt to flee to Indochina if the crew remained aboard, a Royal Australian Navy guard escorted them off Pierre Loti as its Tricolor was lowered for the last time. Since they were neither enemy civilians nor prisoners or war, the officers and their families were put up in Sydney hotels, being required to register with customs officials as ‘aliens’. The ordinary seamen, meanwhile, were transported to North Head, which had effectively ceased its quarantine functions and become a military encampment soon after the outbreak of hostilities.

Although no specific promises were made to repatriate Pierre Loti’s crew to French territory – especially Indochina – this was apparently the Australian government’s underlying intention. But in the context of Axis military campaigns stretching from Norway to North Africa – and compounded by commerce raiders and unrestricted submarine warfare threatening freedom of the seas – the fate of these recalcitrant French mariners soon slid from political prominence.

In Sydney, however, Pierre Loti’s officers remained a most unwelcome presence, especially among the city’s small French community. In December 1940, local de Gaullist Roger Loubère wrote to Sautot in New Caledonia. He accused one of the disembarked officers, Jean de Boisriou, of being ‘a rabid Nazi’, adding that the French Consul-General in Australia, Vichyist Jean Trémoulet, was actively pro-Japanese. Indeed, when the diplomat asked whether Japan could feasibly invade New Caledonia, de Boisriou apparently responded: ‘Yes, in half an hour it would all be over’. Furthermore, added Loubère, Trémoulet pumped de Boisriou full of anti-Australian propaganda in the hope that it would be fed to the Governor‐General of Indochina – Admiral Jean Decoux – thus discouraging him from following de Gaulle’s example by aligning with the Allied cause.

Little wonder that in April 1941 André Brenac, de Gaulle’s representative for Free France in Australia, wrote to Australia’s Minister for External Affairs, Frederick Stewart. Brenac insisted that as Pierre Loti’s former officers continued to ‘do nothing to support the common cause’ they ‘should not be permitted to remain in Australia’ a moment longer. On 6 June 1941, at least some of these unwanted aliens were despatched to Saigon via the Philippines, aboard the Nippon Yusen Kaisha’s, Suwa Maru. Ironically, a month later this steamer was impressed as a troopship to assist with the full Japanese occupation of French Indochina and – in February 1942 – the invasion of Java.

A regular visitor from New Caledonia, Pierre Loti voyaged to Sydney from 1937 until its seizure in 1940. Image: Jean-Paul Fontanon.

Sailors in the sandstone

Not all of Pierre Loti’s crew remained loyal to the Vichy cause, however. From their detention at North Head Quarantine Station, ten sailors of French descent and one of the lascar crew sought permission to remain in Australia. Several were granted their liberty and left Sydney late in May 1941, apparently sailing on several voyages to and from New Caledonia throughout the war. Some did not behave according to their agreements, however. Mechanic Emile Coulomb was interned at Liverpool Camp as a prisoner of war in May 1942, but released on parole three months later. Although eventually repatriated, he regularly returned to Australia after the conflict ended in 1945.

But what of the Vietnamese sailor named Thuam who engraved his homeland – ‘l’Indochine’ – into the North Head sandstone in 1940? It is likely that he made a simple mistake in rendering the date “6 10 40”, since he arrived at the Quarantine Station on 6 November 1940. Given his inscription is in French, he may have been inspired by the many carved memorials to the 1898 quarantine of an earlier Messageries Maritimes liner, Caledonien.

An enhanced scan, using polynomial textural mapping, of an inscription created during the 1898 quarantine for smallpox of the Messageries Maritimes steamship, Caledonien. Despite its name, the ship had sailed to Sydney from Marseilles, not New Caledonia. Image: Pam Forbes and Greg Jackson, Sydney Harbour National Park.

Sadly, little else is known of Thuam’s identity or career, although as late as April 1941 Quarantine Station staff reported that they still held approximately 50 ‘Arabs and Tonkinese’ from Pierre Loti in the station’s Seamen’s Isolation Hospital. Likely they were gradually returned to French territory from May 1941, although it is unclear what effect the Japanese occupation of Indochina had upon such plans.

Beyond this solitary carving facing the open sea, Pierre Loti’s crew were clearly not troublesome detainees. Indeed, in early 1941 their presence provided quarantine authorities with an excuse not to accommodate 80 contract-expired British sailors from the Hired Military Transport Queen Mary. ‘They would be an irresponsible crowd without any discipline or control’, insisted Sydney’s Chief Quarantine Officer, Arthur Metcalfe, ‘and it would be impossible to get rid of them if we had to use the Station for quarantine purposes’.

Ironically, after 1945 quarantines dwindled to nearly nil throughout the 1950s. Concurrently, failed French attempts to regain their colony of Indochina led to a tragic tapestry of hostilities that persisted almost without cease until April 1975. By the time that the Operation Babylift children arrived from Saigon, Sydney’s Quarantine Station was effectively a ghost town. Although their saga remains prominent in Australia’s memories of the dismal finale to the Vietnam War, perhaps in time the fuller story of their Pierre Loti predecessors will also resurface.

— Dr Peter Hobbins, Department of History, The University of Sydney

Peter’s book, Stories from the Sandstone: Quarantine Inscriptions from Australia’s Immigrant Past, was written with archaeologists Ursula K Frederick and Anne Clarke. It reveals dozens of similar tales drawn from over 1600 inscriptions carved into the rocks at North Head Quarantine Station between 1835 and 1984. Stories from the Sandstone won the NSW Community and Regional History Prize in the 2017 Premier’s History Awards. Peter wishes to thank Margaret Barrett and Dr Clara Sitbon for their assistance in locating and translating materials relevant to this story. He is also grateful to Jean-Paul Fontanon, for permission to re-use three images of Pierre Loti from his website, Pierre Albessard: un Grand Marin du Cantal.

The Quarantine Station can be accessed via the Eco Hopper ferry which sails between Circular Quay and Manly. History and ghost tours of the site can be organised via the Q Station website.