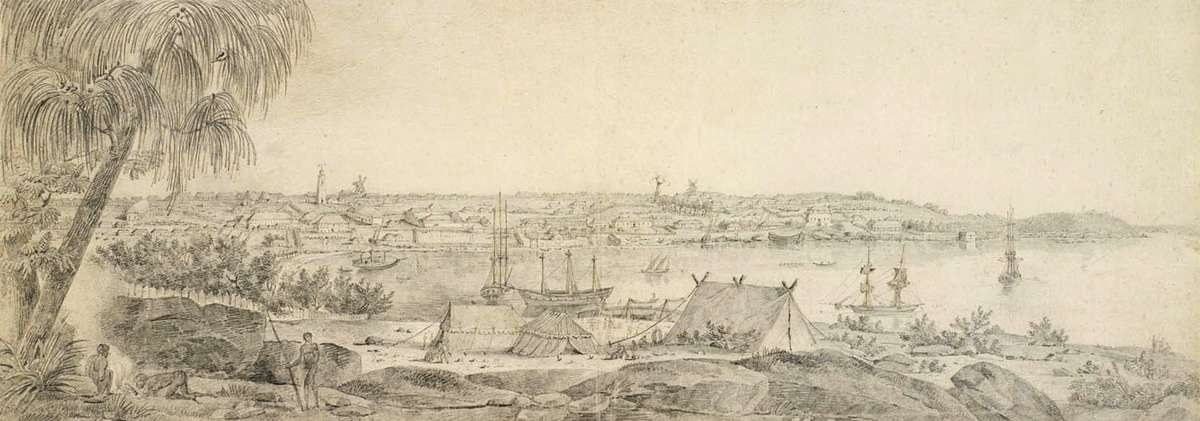

Lesueur made detailed sketches of Sydney. This view was made looking across Sydney Cove from where the Sydney Opera House now stands. Museum d’histoire naturelle, Le Havre.

In April 1802 when the lookout station situated on the southern headland at the entrance to Port Jackson reported the sighting of a French naval vessel approaching, the news spread quickly through the streets of Sydney. Isolated on the far side of the world from England, it was normal for news of the arrival of a ship to cause excitement at the prospect of news from Europe and the hope of fresh supplies. The armed corvette Le Naturaliste however, was an unusual arrival and unlikely to bring much comfort to the town.

Throughout the latter half of the eighteenth century successive British and French expeditions had explored the islands and adjacent coasts of the vast Pacific Ocean gathering information on the people, products, geography and resources of the enormous region – and in the case of Cook, laying claim to large parts in the name of his King.

Placed in this context the Baudin expedition continued an unbroken tradition of the great French scientific expeditions of Bougainville, La Perouse and d’Entrecasteaux, but this period had also been one of enormous political upheaval in France with the execution of the Louis XVI in 1793 leading to the first coalition of European governments opposed to ideals of the French Revolution.

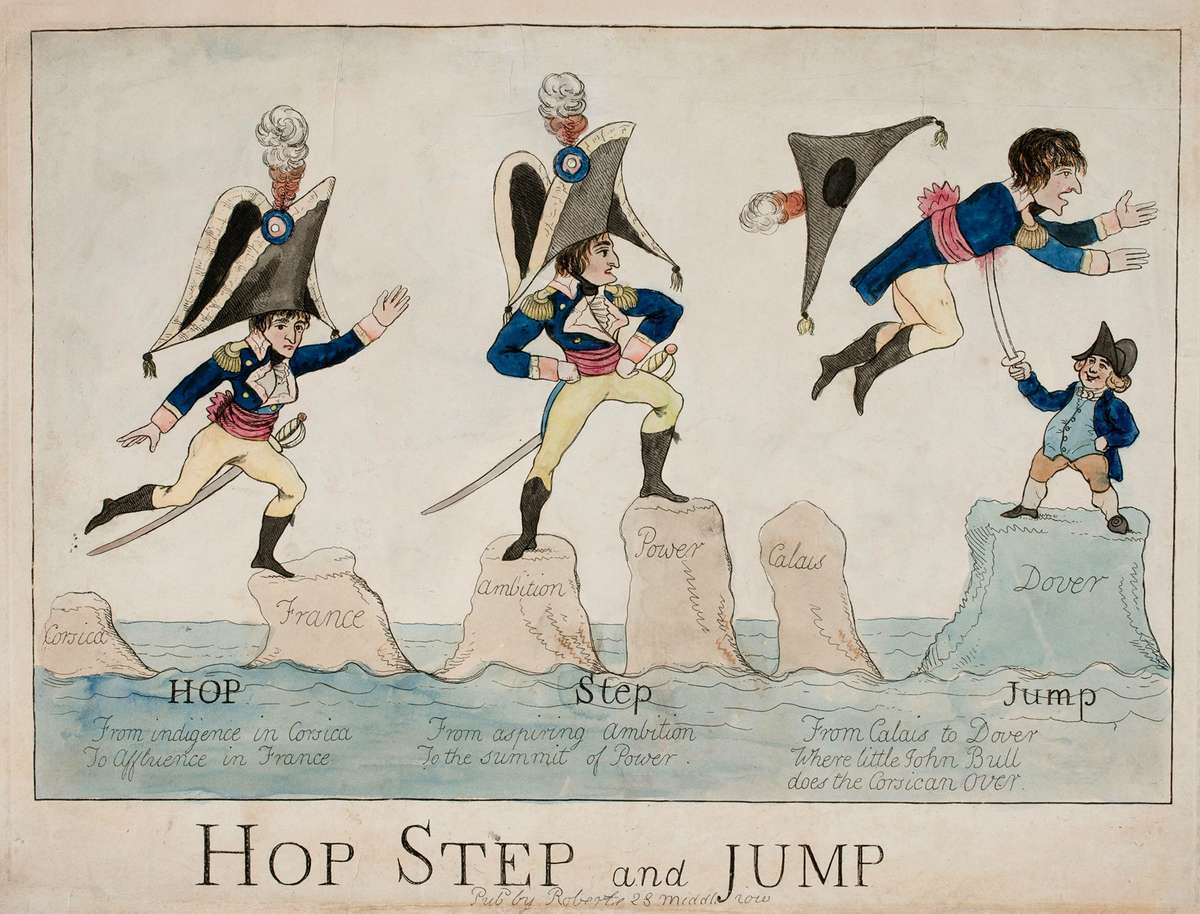

Protected from the wars sweeping the Continent by its powerful navy and the English Channel, Britain had thus been at war with France for eight years by the time Nicolas Baudin’s ships Geographe and Naturaliste sailed from Le Havre in October 1800. The last years of the century had also seen the meteoric rise to power of general Napoleon Bonaparte and the expansion of French ambitions beyond Europe with his invasion of Egypt in 1798. The British destruction of France’s naval support for the Egyptian campaign at the Battle of the Nile effectively stranded Napoleon’s army in Egypt, resulting in the general hastily abandoning his troops and returning to Paris, but despite this failure by the end of 1799 Napoleon had taken the title of First Consul and was busy consolidating France’s military into an ever-more-powerful force.

Le Naturaliste was not entirely unexpected. Sir Joseph Banks had written to Governor King in Sydney about the Baudin expedition after the French authorities applied for a passport from Britain in support of scientific advancement. The passport was granted but privately Banks suspected the French ships were being sent to ensure allegiance to the Republic amongst the populations of the French Indian Ocean islands of Ile de France [Mauritius] and Ile Bourbon [Reunion][i]. Banks stated that while the focus of Baudin’s cartographic work was not the east coast of New South Wales, it was possible that the French would pay a visit to the new colony sometime during their voyage.

As it happened the Geographe and Le Naturaliste had become separated during a fierce storm off the east coast of Van Diemen’s Land [Tasmania] and after searching unsuccessfully, the captain of Le Naturaliste, Jacques-Felix-Emmanuel Hamelin, had headed to Port Jackson looking for Baudin and the Geographe.

The Geographe was not in Sydney but Hamelin received a warm welcome from the colonial authorities, Governor King hosting a ball for the Naturaliste’s officers and providing supplies and assistance to the ship. It was during this time that Matthew Flinders arrived in the Investigator with news of his encounter with Baudin off the south coast.

Despite this welcome news and the knowledge that the Geographe was heading for Port Jackson, Hamelin prepared to leave Sydney intending to return to the Ile de France [Mauritius] via Bass Strait. Hamelin’s encounter with the colonial authorities lasted just three weeks and while his short report detailed the defences and size of the garrison protecting Sydney and its satellite towns, it was largely descriptive and entirely apolitical in sharp contrast to the report later written by Baudin’s zoologist Francois Peron during the Geographe’s five month stay in Sydney[ii].

Francois Peron’s report to General Decaen on the British colony of New South Wales

News of the cessation of hostilities between France and Britain[iii] reached Sydney in May ostensibly bringing to a close almost a decade of war between the two nations. However, few believed the peace was likely to last very long[iv] and indeed in the event, it proved to be the only period of peace between the two between 1793 and 1815. Regardless of the peace, for Francois Peron, the Geographe’s stay in Sydney provided a unique opportunity to assess the British colony and its broader impact and potential to affect the colonies of France and its allies in the Indo-Pacific region.

Caricature, Hop, Step and Jump (1804), hand-coloured etching by Piercy Roberts. A diminutive Napoleon traverses the seas from Corsica to Dover in three stages via a series of rocks marked Corsica, France, Ambition, Power, Calais and Dover. At the last, John Bull, symbolising England, holds a sword upon which Napoleon is impaled as he falls. ANMM Collection 00054712.

Peron would later publish the official account of the voyage, but his report given to General Decaen, the French commander at the Ile de France in 1803, undoubtedly influenced Decaen’s attitude to Matthew Flinders when he arrived at the island a day after the departure of the Geographe.[v]

Peron’s report ends with the strong recommendation that the colony of New South Wales … ‘should be destroyed as soon as possible’ and that – ‘We could do it easily now; we will not be able to do it in 25 years’ time.’[vi]

In its structure the report lists the advantages Britain gains from having a rapidly expanding colony located strategically on the edge of the Pacific Ocean with ample territory to expand and with many commercial resources. Peron describes the town of Sydney and its satellite towns and gives detailed population figures to show how quickly the colony has expanded since its foundation some 14 years earlier, extending its reach in every direction and effectively making good the vast territorial claim made by Britain at the time of settlement.

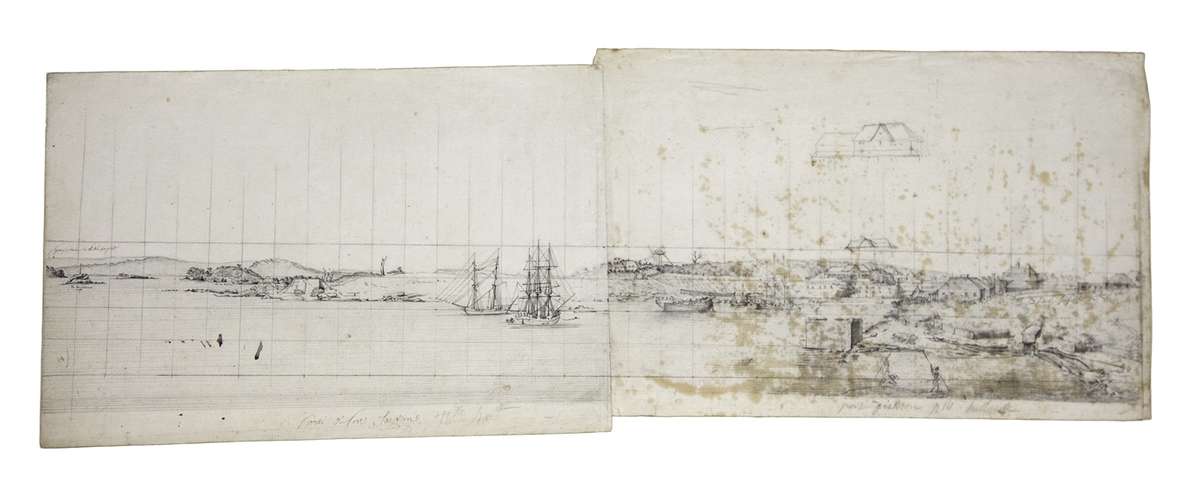

Lesueur’s panoramic drawing of Sydney Cove, looking east from the Dawes Point Battery. Museum d’histoire naturelle, Le Havre. Click to enlarge.

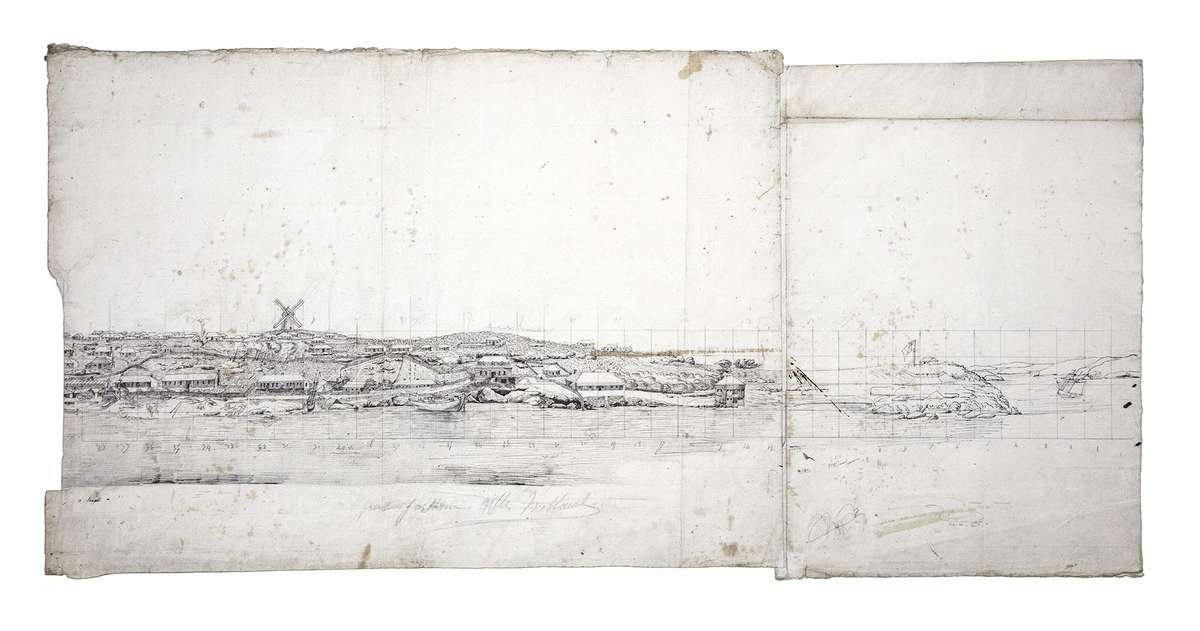

Lesueur’s panoramic drawing of Sydney Cove, looking west from where the Sydney Opera House stands today. Museum d’histoire naturelle, Le Havre. Click to enlarge.

He paints a picture of a thriving colony with successful whaling and sealing industries, productive farms producing large quantities of wool, hemp and wine, and a burgeoning trade with China and the Pacific islands – all well-supported by the British government through its system of convict transportation and its investment in its military administration and infrastructure. Indeed, the colony is so successful that if it continues to expand unchecked, France’s ambitions in the region will be lost altogether.

But for Peron (who claimed to have gathered a large amount of valuable information without raising suspicion)[vii] this threat to France could still be overthrown by sending a French force to attack Sydney from a landing in Botany Bay. The arrival of a strong force would easily overcome the poorly-trained and widely dispersed British garrison and would be supported by a spontaneous uprising of the Irish convicts. Together this force would overcome the inadequate military and naval defences protecting the colony.

Lesueur’s map of Sydney and surrounds, with prominent government and military positions marked. Museum d’histoire naturelle, Le Havre.

In this context Lesueur’s detailed map of Sydney and its environs and his several views of the town’s principal buildings take on a more sinister and strategic importance as they indicate the location of the Government commissariat stores[viii], Military barracks[ix], gun batteries[x], prison[xi], Governor’s house[xii] and house of the military commander.[xiii]

While it was completely normal for foreign officers visiting the ports of rival nations to record details of what they saw[xiv], Peron’s report went far beyond mere description to become a vehicle for expressing his own highly subjective views. Regardless of the warm welcome Baudin’s men received in Sydney from Governor King in 1802, a reading of August Peron’s report clearly reveals that for him the friendship was a short-term convenience – a lull in the battle between France and Britain which had raged for centuries and within months would threaten the invasion of England.

— Nigel Erskine, Head of Research.

Art of Science Baudin’s — Voyagers 1800-1804 is part of our FREE galleries ticket.

This article originally appeared in Signals 120 (September 2017). Uncover more maritime history and stories in our quarterly magazine Signals.

The museum would like to advise visitors that this exhibition may contain names and images of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Further reading

[i] Mitchell Library, King family – Correspondence and memoranda, 1775-1806

A 1980/2 CY 906, p.37. Cited in Fornasiero, J. and West-Sooby, J. 2014, French Designs on Colonial New South Wales, published by The Friends of the State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, p.60

[ii] The Geographe entered Port Jackson 20 June 1802 and departed 18 November.

[iii] The Treaty of Amiens was signed in March 1802.

[iv] It lasted only until 18 May 1803.

[v] Flinders arrived at Ile de France on the schooner Cumberland 17 December 1803.

[vi] Francois Peron’s Report to General Decaen, 1803 in Fornasiero J and West-Sooby J, 2014 French Designs on Colonial New South Wales, Friends of the State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, Appendice 1, p.317

[vii] Ibid, p.293

[viii] Three buildings each marked ‘B’ on Lesueur’s Plan de la Ville de Sydney

[ix] Marked ‘F’

[x] Two batteries, one on either side of the entrance to Sydney Cove, each marked ‘M’

[xi] Marked ‘H’

[xii] Marked ‘D’

[xiii] Marked ‘E’

[xiv] See for example James Cook’s description of the Portuguese forts defending Rio de Janeiro, in The Journals of Captain James Cook – The Voyage of the Endeavour 1768-1771, (Edited by JC Beaglehole), Cambridge University Press, 1955, p.31