At 22 metres tall Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse seems a solid, immovable structure. In fact, it was designed for ready disassembly and has been moved at least three times in its 150-year life. It has also been continuously modified throughout its history. The lighthouse at the museum is only partially the lighthouse that was built at Cape Bowling Green in 1873-4. The lighthouse and its changing history challenges ideas about the preservation of immovable cultural heritage.

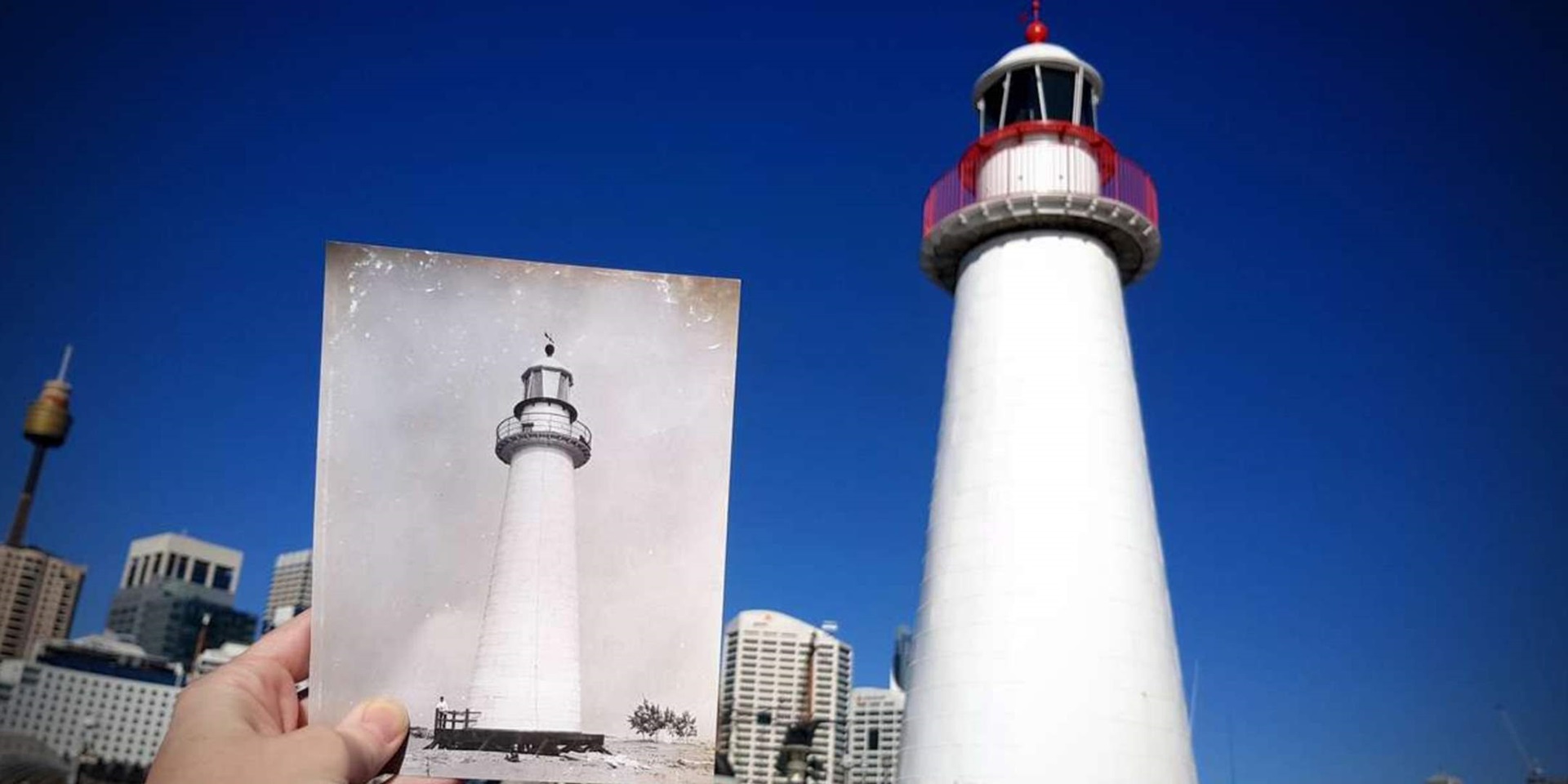

Cape Bowling Green lighthouse in 1917. Image: National Archives of Australia A6247 B32.

Immovable cultural heritage is cultural property inextricably tied to place or intended to occupy a particular location. Examples of immovable heritage include archaeological sites, monuments, rock art and buildings. Generally speaking, attempts to relocate these heritage items or their content can result in damage and a loss of meaning. Cultural heritage professionals usually seek to preserve immovable heritage in its original location.

The parts making up the original lighthouse had a penchant for travelling even before assembly. It appears that the metal cladding, cast iron lantern room, mechanism and lens were manufactured in Britain. The ironbark timber structure was milled and fitted in Maryborough, then shipped out on the schooners Henry Albert and Fairy to the Cape. The lighthouse apparatus was shipped from Brisbane on the schooner Dawn.

Map of Cape Bowling Green, 1927. Image: National Archives of Australia BP374/1 NEG6541.

Cape Bowling Green is a sandy spit jutting out into the Coral Sea about 70km south of Townsville. Joseph Henry Carter attended the light at Cape Bowling Green for a year from 1910. His son Bill Carter recorded the mobile nature of the lighthouse:

‘Cape Bowling Green… was nothing but a sandy flat, mostly tidal flats, especially at king tides. Three times, erosion of [the] outer beach made it necessary for the lighthouse to be shifted back from the sea, the last time it was moved it was rebuilt on a wooden frame base… A great disaster not far from Cape Bowling Green was the loss of the Yongala… My Dad was on watch in the lighthouse when the worst of the blow was on, and he said that the tower literally danced on its foundations… [as the] main bolts to hold it to the foundation had not been replaced when the last shift of the tower was done.’

Newspapers record the lighthouse being moved in 1878 and 1908. Erosion of the Cape in 1875 and 1904 endangered the lighthouse, but it may not have been moved on these occasions. The 1908 move was the most arduous. The lightkeepers initially retrieved the lens and mechanism using a derrick, and moved them to the nearby keepers’ cottages with a goat team. The lighthouse was soon afterwards disassembled and moved, piece by piece, to high ground at the end of the Cape – 1200 feet from its last location. During the process:

This was not the first or last time the lighthouse was changed. Perhaps the most significant modification was destaffing and automation in 1920. The kerosene fuel system was replaced with acetylene and a sun valve controlled the operation of the light.

Preliminary sketch for the conversion of the lighthouse to an unmanned configuration, 1918. Image: National Archives of Australia A9568 3/1/2.

Much more recently, the museum replaced the damaged weathervane and the front door. Photographic evidence showed that the weathervane was not original. The National Archives holds records demonstrating that the door dated from 1979.

How do we understand and care for a lighthouse which is not in its original location or composed entirely of original historic fabric? Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse is not static. It exists in a continuity of change in our care, consistent with its in-service life.

The lighthouse is no less valuable or interesting for being composed of layers of history. Elements of the lighthouse will continue to be replaced as necessary to keep the structure sound, secure and available for visitors to enjoy. In line with conservation ethics, we will intervene as little as possible, and maintain as much of the as-collected fabric as we reasonably can.

— Rebecca Dallwitz, Senior Objects Conservator.

Look out for our next blog on the 1987 dismantling of Cape Bowling Green for its move to the Australian National Maritime Museum.

The museum is carrying out essential conservation on the lighthouse. This work is made possible by a generous donation from the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA). The lighthouse will be accessible during International Lighthouse Weekend on Sunday 20 August from 1-4pm. Please contact us for opening hours on other days.