Fifty years ago, in August 1967, Australian yachting made history on the world stage, winning the Admiral’s Cup event sailed in UK waters, then recognized as the unofficial world championship for ocean racing.

It was only the second time an Australian team had entered the event, which, up to then, had been dominated by yachts from the UK and USA. The result was astonishing at the time – similar to Australia beating Brazil in a final of the World Cup.

This is part one of a two part story of that remarkable victory.

A famous Beken of Cowes image of Caprice of Huon on the Solent in 1965

A warning shot was fired in 1965 with our first challenge. That Australian team, politely referred to as ‘old cruising yachts’ by the establishment, came second with the 13-year-old Caprice of Huon the team’s top individual yacht.

The 1967 win was as emphatic as it could be: more than 100 points clear of the next team.The top three individual yachts of all yachts competing were the three Australian entries – Mercedes III, Balandra, and Caprice of Huon.

The top boat, Mercedes III, was designed (by Ben Lexcen) and built in Australia.

Sorry, There’s A War On

But the Australian challenge almost came to nothing even before the yachts had arrived in the UK. They left aboard the Wilhelmsen cargo ship MV Tysla which steamed toward Europe intending to take the usual passage through the Suez Canal. As the ship crossed toward the Red Sea, the June 6-day Arab-Israeli war closed the canal, and it became apparent that there was little chance of the canal reopening soon.

MV Tysla had to return to Fremantle to offload cargo originally bound for Aden and then, like many other ships, headed west for a passage around the Cape of Good Hope. Its schedule was now even further delayed, as it would have to go into the Mediterranean Sea for a scheduled stop at the Italian port of Genoa, before eventually reaching the UK. It looked like they would miss the Admiral’s Cup entirely.

The Kindness of Strangers

Mercedes III owner Ted Kaufmann flew to Capetown and his call for help was answered with great generosity. In Capetown Tysla was given precedence over other ships so that members of the Royal Cape Yacht Club could assist and offload the three yachts, transferring them to a Union Castle Line passenger ship that arrived in Southampton on July 17 – right in the middle of a waterside workers’ strike.

Sending a team from the other side of the world was always going to be demanding. It had to be selected well in advance of the Northern Hemisphere teams. Extra weeks were lost due to travel, and with the boats having to be unrigged, packed up, then set up again. The determination to get there, despite these additional obstacles, added to the resolve of the Australian crews.

As July closed, all competing teams assembled in Cowes, eventually joined by the Australian boats, and took part in warm up races. The Australians were prepared, but were the other teams aware of what they would be up against?

Previously, the UK, European and US sailors recognized that the Australians had experience through their many ocean-racing events, including the Sydney to Hobart race, they did not consider Australia to be a significant threat to their supremacy. The success of the Australian’s 1965 campaign caught them by surprise, and changed all that.

Camille of Seaforth on Pittwater in 2008

1965: The Australian Shock

In the aftermath of the Australian team’s surprise second place in 1965, Australia’s opponents were on high alert.

In particular they singled out the leadership of Gordon Ingate and the determination of the Australians to sail as well as they could as a team.

Yachting Monthly in September 1965 noted “Cowes week will quite certainly be remembered for the first visit of the Australians… Australian yachtsmen made an immediate and impressive impact upon British sailing… the factor mainly responsible for Australia’s success was perhaps not to be found in the boats but in the men who sailed them.”

The locals remained bemused by the collection of yachts, however:

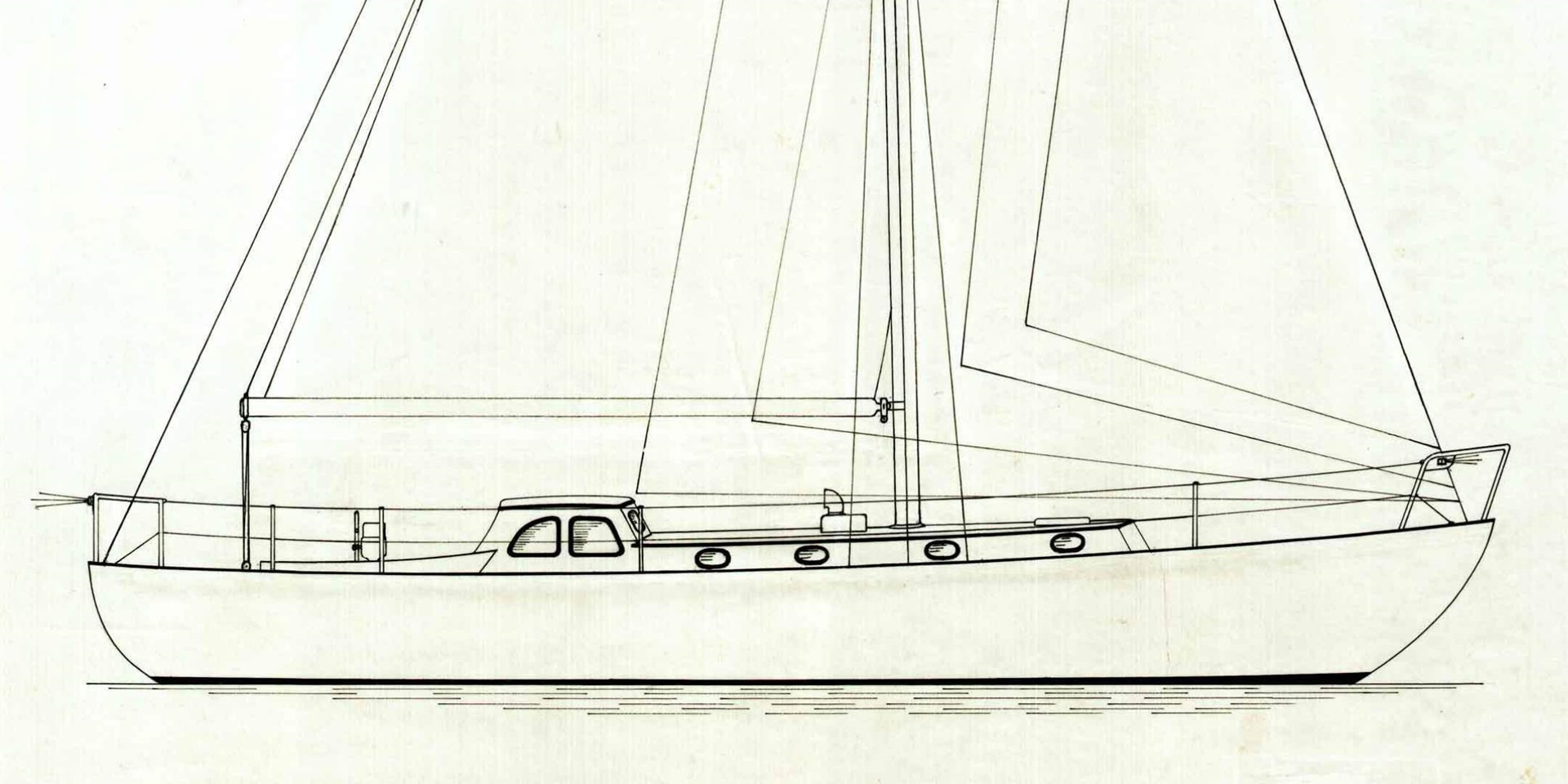

“Caprice of Huon – a 13-year old Robert Clark design in which modernisation had been applied to almost everything except the hull… and her canoe sterned colleagues, the Halvorsen Bros sophisticated Freya, and Ron Swanson’s unpretentious Camille with light weight (and bent) fittings, a 4 inch cockpit compass and a sail plan so modest that with a 30 ft waterline she rates in RORC Class 3.”

How dare they be so good at their first try with this assortment of craft? Yachting World (UK) summarised things well from a British perspective:

“If it was the Admiral’s Cup which dominated Cowes Week, it was the Australian team’s spirited attempt to win it that dominated the Admiral’s Cup. Everyone admired their tremendously sporting effort in bringing a team of yachts from the other side of the world and when Caprice of Huon won her class in the Channel Race, people reckoned it was a fair reward. When she won the Britannia Challenge Cup outright, they were astonished and when she completed a fabulous hat-trick by winning the New York Yacht Club trophy, Gordon Ingate and his crew were confirmed as the heroes of the week. The way they managed to drive their elderly, amateur built yacht, whose long ends give her a stiffish rating, so well as to consistently beat the very latest and best from seven other countries, made a deep impression”.

1967: Still Considered Underdogs

In 1967 Caprice was back, but without Gordon Ingate, who had been involved in the 1967 America’s Cup challenge. His 1965 sailing master, Gordon Reynolds, was now at the helm, so little, if anything, was lost.

Balandra was a copy of top UK yacht Quiver IV from 1965 and superbly prepared, while Mercedes III was the dominate yacht in the Australian trials, and about to show the world the talent of Bob Miller, thanks to the support of Ted Kaufmann. The enthusiasm of the new members was combined with the experience of returning 1965 sailors, and they prepared as a team.

Recognising that a key to success was understanding the difficult tides and currents of the Solent and the Channel, all three Australian navigators worked together for months in the lead-up. They spent time at Southampton University studying a working model of the Solent to become familiar with what to expect.

The yachts were better prepared, too. Any weakness upwind that had been felt in 1965 was covered by the abilities of the yachts chosen. They were ideal for the range of prevailing conditions, crewed and rigged to the equal of any of the other craft.

Despite this, a hint of complacency in the UK was already showing soon after the 1965 event. Yachting magazine in October 1965 noted that “since some of the best Aussie sailors will be striving for the America’s Cup in 1967 it is problematical whether the CYC of Australia will challenge for the Admirals Cup”. In hindsight that showed a misjudgement as to how well resourced Australia was in being able to put together both challenges in the same year. The local talent spread across the two events was impressive.

The 1967 Admiral’s Cup series: What’s to Come in Part Two

The racing of the 1967 Admiral’s Cup series provided a fine spectacle. There was tight, boat-to-boat competition in light winds, strong winds, tides, damage and controversy, all of which the Australians mastered, and gave a lesson in sailing to the other teams. We will look at that and the boats in a second instalment.

Fifty years later the extent of this overwhelming win has never been repeated. Australia managed two more victories, and many high places in subsequent years until the competition was unfortunately abandoned. The Cup has not been contested since 2003, but in that series an Australian team were the last winners, so 50 years on from 1967 we once again hold the trophy!