Green job-fish (Aprion virescens). ANMM Collection 00019588. Gift from Walter Stackpool. Reproduced courtesy of Dr Jane Stackpool.

One of the issues we readily face in the museum world is how to increase the proportion of our collection that is accessible to the public. The unfortunate reality is that due to collection size and the display space available the percentage of the collection on display at any one time is limited to approximately 9%.

The solution: digitise.

Showcasing the other 91% of the Collection

Driven by the museum’s transition to the digital era and the need to increase the number of items accessible to the public, the Registration team is working steadily to digitise the collection and update databases to help reach external museum visitors.

Other positives of digitising the collection for outreach are that it also preserves the collection: reducing light exposure and the need for human handling.

In terms of the digitisation project, I work in close proximity with the Photography department. Whilst Photography is primarily concerned with large-scale and 3D objects, I deal with the archive based material which is scanned on a flatbed scanner. While the process of scanning material to set parameters each day may seem like a monotonous task, it is an essential and at times complex role.

The Whale Song of the Flatbed

The sound of the flatbed scanner in action has been lovingly referred to as ‘listening to a whale song.’ Scanners work by controlling the amount of light that is reflected off an object, with differences in reflected light representing different colours and shades. Sometimes slight inaccuracies can occur as to what it detects, and what is visible to the eye.

All the images I scan must first be edited before being uploaded to ensure they are an accurate representation of the current state of the object, regardless of its physical defects. This can involve changing the hue, saturation and subtle colour differences that a scanner can marginally distort. Should a reproduction of the scanned object be reproduced, the master file should replicate the original in terms of visual and physical size as much as possible.

Scanned image which has been distorted by a scratch on the surface of the flatbed scanner. ANMM Collection ANMS1350[080]

Foreign matter inside the scanner or scratches on the physical surface of the scanner can also distort the scanned image. Dust can change the reflection of the light, creating red, green and blue lines which run the length of the image, and scratches are clearly visible. When distortions occur on a close up photograph, written document or 35mmm slide they are much easier to identify and edit than photographs taken from a distance or large paper-based objects.

Having to adjust a scanned image is not uncommon. It is a process that cannot be done in bulk. Whilst the defects of dust and scratches can be avoided through equipment maintenance and the use of Mylar sleeves for glass plates, correcting irregularities in colour and tonal readings cannot. All must be looked at closely before finalising.

A Fish Tale

As an example, I recently scanned a collection of watercolours by Australian Artist Walter Stackpool who created them for use in Jack Pollard’s 1978 book titled Australian Fishes. As Pollard’s book is a guide for spotting Australian fish, Stackpool’s work is accurate in illustration and its use of colour. Each watercolour was painted onto an artist’s board of various sizes with sometimes three fish to a board. Some boards had to be scanned in two halves, with one fish split across two scans, and then blended together in order to capture the full fish.

There were many occasions across both scans where the fish was the right colour but the wrong tone, or four out of five colours were correct but one was not. Balancing the colours was complex and time consuming, as was combining two scans to make a single image.

Trumpeter whiting (Sillago Maculata), John Dory (Zeus australis) and River gar (Hemirhamphus ardelio). ANMM Collection 00000617. Gift from Walter Stackpool. Reproduced courtesy of Dr Jane Stackpool.

High Resolution Images

Appropriate storage of scans can also be an ongoing issue as the original scan is saved as both a TIFF and JPEG formats. TIFFs are extremely large files but are necessary as they contain all the raw, uncompressed metadata of an image that travels with it whenever it is downloaded or opened. Essentially the TIFF can be converted into any file type for any purpose; a digital master of the original document.

The specifications for the TIFF determined as ‘best practice’ by museums are currently at 4000 pixels per inch (PPI) on the shortest edge and a minimum resolution of 300 (single negatives have a resolution up to 4800). It’s not a simple matter of increasing the PPI of an already saved image up to 4000, this only results in the image becoming ‘stretched’ as blank pixels are added to increase the size. The whole point of the exercise is to preserve to the best standards currently available the greatest amount of detail in case the original is not available in the future.

![Jack Eden, Presentation of the trophies in the first world open surfboard championships Manly, 1964. Gelatin silver photograph, printed 1990s. Senior men’s championship winners on the podium: 1 Midget Farrelly, Australia (centre), 2 Mike Doyle, California (left), 3 Joey Cabell, Hawaii (right). The women’s championship winners are on the right: 1 Australian Phyllis O’Donnell (far right) and 2 Linda Benson California (right), with Nat Young, the runner-up in the junior men’s final, on the left. ANMM Collection ANMS1078[004], ANMM Collection Gift from Jack and Dawn Eden.](https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/anmm-data/blog/2017/07/04/anms1078004.jpg)

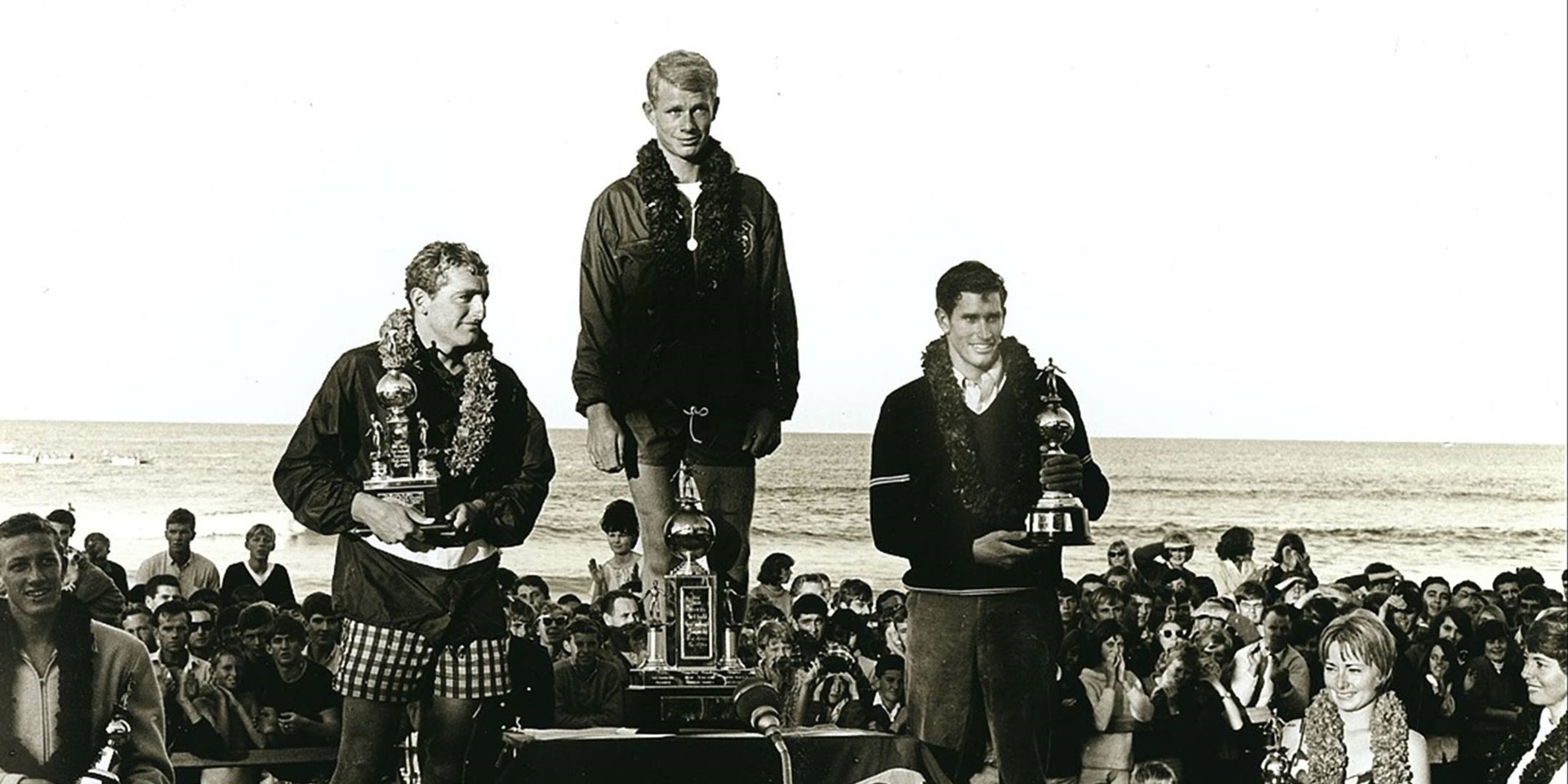

Jack Eden, Presentation of the trophies in the first world open surfboard championships Manly, 1964. Gelatin silver photograph, printed 1990s. Senior men’s championship winners on the podium: 1 Midget Farrelly, Australia (centre), 2 Mike Doyle, California (left), 3 Joey Cabell, Hawaii (right). The women’s championship winners are on the right: 1 Australian Phyllis O’Donnell (far right) and 2 Linda Benson California (right), with Nat Young, the runner-up in the junior men’s final, on the left. ANMM Collection ANMS1078[004], ANMM Collection Gift from Jack and Dawn Eden.

Copyright Conundrums

Ensuring that the collection is ready for online display poses another dilemma, that of copyright. As the world becomes more digitally orientated understanding the application of copyright becomes more crucial, especially when content is shared.

High resolution images keeps details clear when zoomed. ANMM Collection ANMS1078[004].

Establishing the legal copyright ownership for some works can be exceedingly difficult, especially when most objects are covered by ‘lifetime of the artist plus 70 years’ condition. This makes it extremely difficult for institutions to share interesting and valuable collection material for online public use.

Fifteen different fishes. ANMM Collection 00000606. Gift from Walter Stackpool. Reproduced courtesy of Dr Jane Stackpool.

Issues of copyright are not something that can be overlooked, as the consequences of breeching copyright are severe. I was reading over the ‘deed of gift’ for a collection pertaining to the life of Captain Dun. Captain Dun had a very long history in the waters of the world from his life in the merchant navy, a Japanese prisoner of War in World War II, the long battle for compensation from the government on the liquidation of Japanese assets after the war, to Captain of the Eastern and Australian Shipping Company, and as a consultant over the Tasman Bridge disaster.

The collection totals more than 1000 individual objects including documents, photographs, negatives and letters. The donors, who were Dun’s children, had signed the intellectual property of all the objects, including the photographs, to the museum.

However, the copyright of photographs is bound by a different law; whoever takes the photograph (thereby the entity responsible for its creation) holds intellectual property and therefore distribution of that work, not the person who owns the equipment (unless specified in another agreement).

Detail captured in high resolution scans. ANMM Collection 00000606.

As Dun featured in nearly every photograph, and as selfie sticks were not in existence at the time, the intellectual property of the photographs was not the donors to grant. The photographs were also taken after 1st January 1955, so are still covered by copyright.

Whilst it would and has been argued that this is a technicality and concessions should be made, it is important to remember that laws such as these have been established to ensure that creators of works are not exploited. This is of mixed consolation when there are many works in the collection for which the copyright status is unknown.

Six P&O Queens

Of course, my role isn’t just defined by digitising the collection; it also involves a large amount of data clean-up. This could be anything from adjusting spelling or titles, to adding constituents, geographic terms, descriptions and places of manufacture. By doing this it is easier to draw connections between records, extending the connection that can be made between materials in different areas of the collection.

An example of the photography studio’s digitisation work. P&O Royal Mail Liners to Tasmania, designed by Frank Norton. ANMM Collection 00027982. Reproduced courtesy of P&O Heritage and Lynne Norton.

A prime example of this was the amendments made to the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) material. When going through a collection of menu covers that depicted the Queens of England, it was noted that of the many duplicates, only four were attached to the constituent record of the artist, Dorrit Dekk. Dekk produced the collection specifically for the Orient Line (The Orient Steam Navigation Company, the Orient Line, was absorbed by P&O in 1966).

I stumbled across the many duplicates when I was going through other identified P&O material. Furthermore, I discovered that rather than only having four of the six in the ‘Queens of England’ series, we did in fact have all six numbered variously as an archive series (a collection of archive based material from an individual owner/collection) and National Maritime Collection (individual objects acquired).

After searching through the collection I thought we may have only had five, as the final missing queen, Queen Mary II, of the House of Stuart, had neither an image of the menu cover (only the menu) nor an attributing title. It was listed only as ‘SS OTRANTO dinner menu’ and had a constituent link only to the donor, not to the Orient Line, P&O or the artist. Now because all records have updated constituent links, the online user will be able to view the full collection, linked by artist. These will soon be available for viewing online.

The online collection will continue to develop over the coming years, continuously with new content, hopefully with new capabilities. It is a work in progress, while there are areas of the online collection that have limited content it could be due to any of the outlined areas above. Whilst we may not have the conveyer-belt and high-speed cameras of the National Museum of Natural History in American who notched up an impressive million digitised objects in a year and a half with a team of five dozen; our comparatively modest team has in the past two years digitised over 66, 300 objects across both archive and 3D material.

What I have endeavoured to detail here is that the process of museum digitisation is definitely not a straightforward task. In completing this task I am extremely privileged – not only do I get to handle some incredible material, but in doing so I learn so much about people, objects and histories to which I have never been exposed, as well as helping to ensure their accessibility for others to discover and enjoy by online viewing. To me this highlights the very nature of what a museum is, and what a museum has the capacity for. Hopefully through digitising the collection the museum will extend this self-directed learning to the broader community.

— Nicole Dahlberg, Digitisation Officer, Registration.

Explore our collection online

![ANMS0497[031] SS OTRANTO 11 November 1956 Queens of England menu card series - HM Queen Elizabeth II, House of Windsor. ANMM Collection ANMS0497[031]. Dennis McLoughry. Reproduced courtesy of P&O Heritage.](https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/anmm-data/blog/2017/07/04/anms0497031.jpg)

![ANMS1355[040]_2 SS OROSOVA 22 December 1958 Queens of England menu card series - Queen Victoria, House of Hanover. ANMM Collection. ANMS1355[040]. Gift from Jenifer Dhu. Reproduced courtesy of P&O Heritage.](https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/anmm-data/blog/2017/07/04/anms1355040_2.jpg)

![ANMS0497[028] SS OTRANTO, 27 November 1956 Queens of England menu card series - Anne, House of Stuart. ANMM Collection ANMS0497[028]. Gift from Dennis McLoughry. Reproduced courtesy of P&O Heritage.](https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/anmm-data/blog/2017/07/04/anms0497028.jpg)

![ANMS0497[029] SS OTRANTO, 18 November 1956 Queens of England Series - Elizabeth I, House of Tudor. ANMM Collection. ANMS0497[029]. Gift from Dennis McLoughry. Reproduced courtesy of P&O Heritage.](https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/anmm-data/blog/2017/07/04/anms0497029.jpg)

![ANMS0497[032] SS Otranto 9 November 1956 Queens of England menu card series - Queen Mary I, House of Tudor. ANMM Collection. ANMS0497[032]. Gift from Dennis McLoughry. Reproduced courtesy of P&O Heritage.](https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/anmm-data/blog/2017/07/04/anms0497032.jpg)