Dirk Hartog plate, 1600–1616. Tin alloy (metal), 36.5 cm (diameter). Reproduced courtesy Rijksmuseum

This week a very special piece of pewter is coming to the museum … the Hartog plate, on loan from the Rijksmuseum to mark 400 years since Dutch mariner Dirk Hartog made the first recorded European landing on the west coast of Australia in October 1616. As a testimony of his visit, Hartog left behind an inscribed pewter plate that is recognised as the oldest European artefact found on Australian soil.

Much has been written over the years about Hartog’s fateful landing in the Dutch East India Company (VOC) ship Eendracht, but what about the physical object, the pewter plate, itself? As a museum curator, I am fascinated by the materiality of the Hartog plate and the many stories embedded in its historic fabric – of trade, exploration, navigation, unknown coastlines, chance encounters, material preservation and the enduring power of tangible cultural heritage.

The Hartog plate is typical of the large pewter serving plates that were used in the great cabins of VOC ships. Now more than 400 years old, it consists of 17 separate fragments that bear witness to the object’s tumultuous history.

Dirk Hartog landing site 1616 at Cape Inscription, Dirk Hartog Island, Western Australia. Photographer Nicola Bryden. © Copyright Department of the Environment

In 1616, the plate was hammered flat and inscribed with a sharp tool, which weakened its structure. It was then nailed to a wooden post on a rocky cliff top, overlooking what is now known as Cape Inscription on Dirk Hartog Island in Shark Bay, and exposed to decades of sun, wind and salty air. These conditions made the plate more susceptible to corrosion. Rijksmuseum conservators have aimed to preserve the Hartog plate in its most complete and authentic state, so that it remains legible and accessible for future generations. For metals conservator Tamar Davidowitz, this has meant reversing past treatments and removing all unoriginal materials from the plate, to acknowledge that the object’s intrinsic value lies not in its aesthetic appearance, but its provenance.

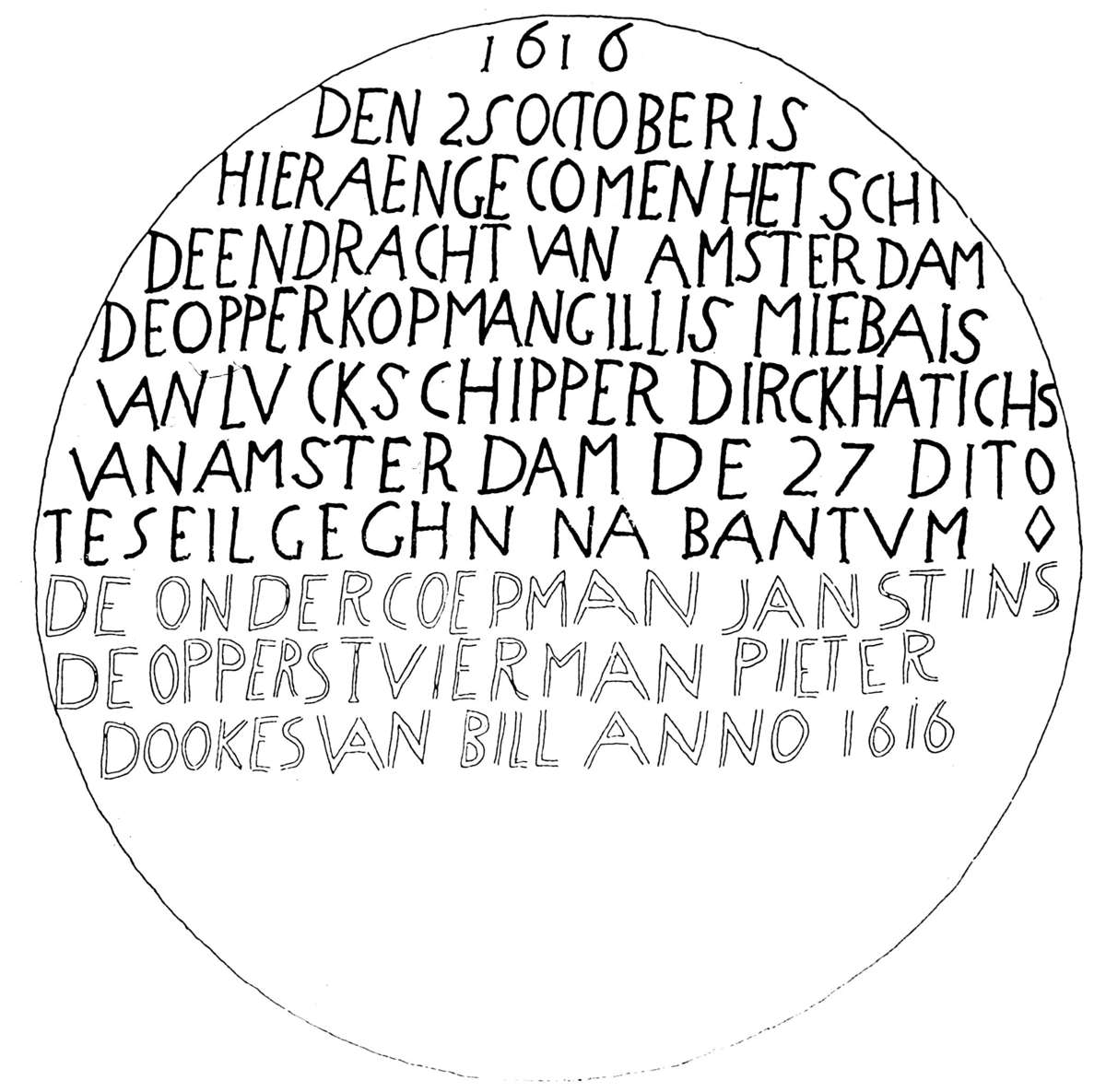

Transcript of the inscription on the Hartog plate. Reproduced courtesy Phillip Playford. The Dutch inscription is translated as: ‘1616, 25 October, is here arrived the ship the Eendracht of Amsterdam, the upper-merchant Gillis Miebais of Liege, skipper Dirck Hatichs [Dirk Hartog] of Amsterdam; the 27th ditto set sail again for Bantam, the under-merchant Jan Stins, the upper-steersman Pieter Dookes van Bill, Anno 1616′

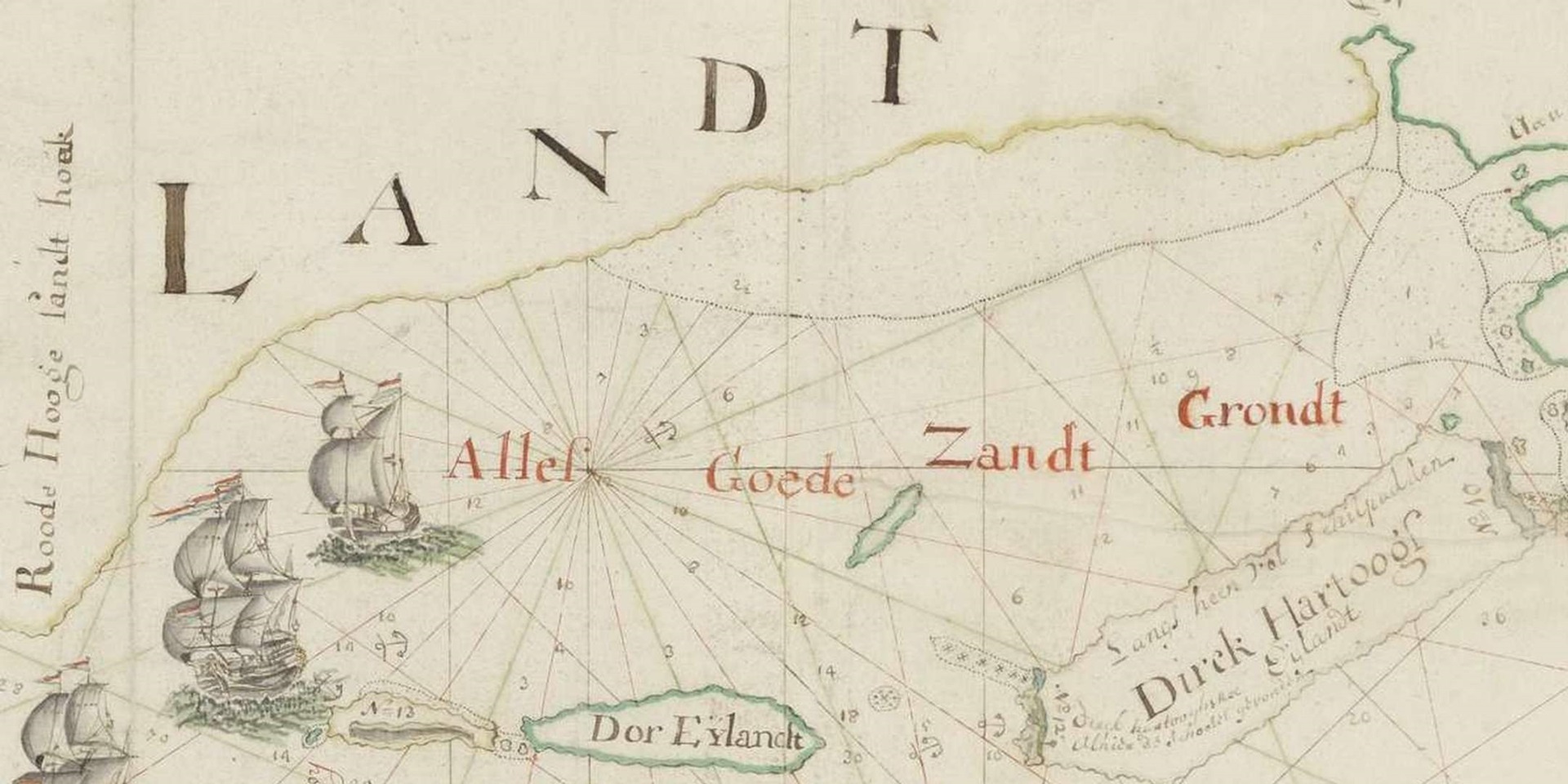

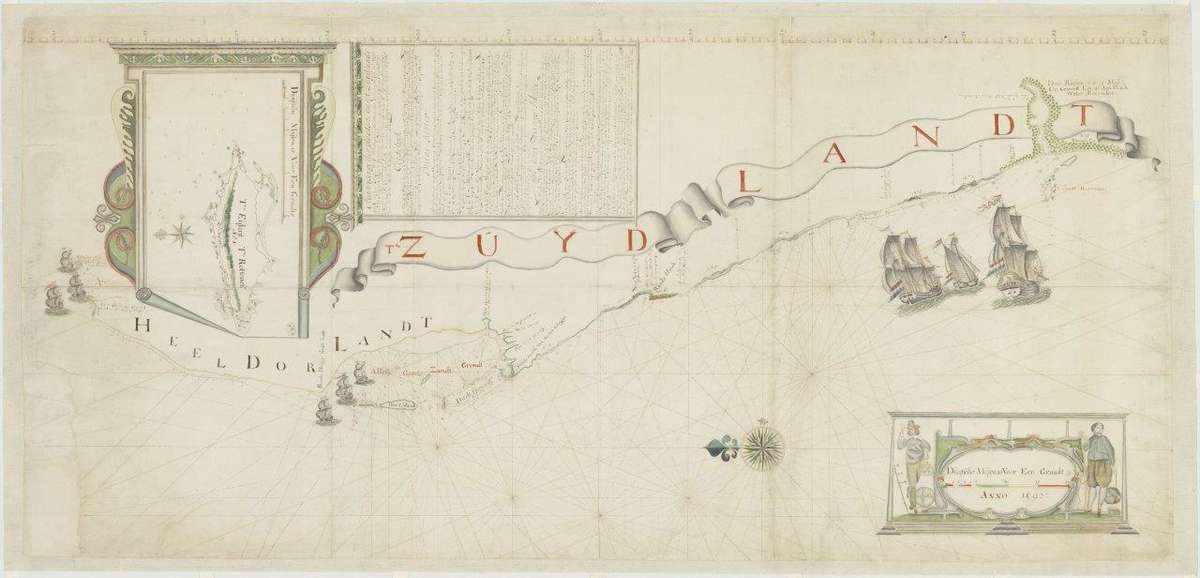

Victor Victorsz, Chart of Willem de Vlamingh’s expedition to the South Land, showing Dirk Hartog Island and the ships Geelvinck, Nyptangh and Weseltje, 1697. Reproduced courtesy National Archives of the Netherlands

When de Vlamingh and his crew landed at Dirk Hartog Island in February 1697 and discovered the Hartog plate, they immediately appreciated its historical significance. The artist on board, Victor Victorsz, created a series of delicate watercolour views of the Western Australian coastline from the Swan River to Shark Bay (now held in the Maritime Museum Rotterdam), as well as a most exquisite map (now in the National Archives of the Netherlands) depicting Dirk Hartog Island with the inscription ‘alhier de schootel gevonden’, which refers to the ‘plate found here’. De Vlamingh replaced the Hartog plate with a new one engraved with Hartog’s message and details of his own visit, and delivered the original to Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia), from where it was sent to Amsterdam and eventually to the Rijksmuseum. The de Vlamingh plate was recovered by French explorer Louis de Freycinet in 1818 and taken to Paris.

Victor Victorsz, Detail of Willem de Vlamingh’s expedition to the South Land, 1697. The inscription ‘alhier de schootel gevonden’ refers to the ‘plate found here’. Reproduced courtesy National Archives of the Netherlands

In 1947, the year the de Vlamingh plate was returned to Australia by the French government, Western Australian writer Peter Hopegood published a poem titled ‘Dirk Hartog’s Plate’ that vividly evokes the ‘Amsterdam ships’ chandler’s platter/Taken and set/Afar from galley reek and clatter.’ It reminds me how wonderful it is that an object as tactile and domestic as a pewter plate – so ordinary yet also extraordinary – connects Australia and The Netherlands across four centuries of shared history.

Discover more about Dirk Hartog in our feature story, A Chance Encounter.