Roald Amundsen with his dog Pan and ship Fram near his home at Svartskog, Norway in the days before leaving for the secret expedition to attempt the South Pole near his home at Svartskog, Norway. Image: Photographer Anders Beer Wilse, June 1910, courtesy Fram Museum.

‘Race to the Pole – Captain Scott successful’ claimed The Age’s headline writer on 8 March 1912, the day after Norwegian adventurer Captain Roald Amundsen slipped quietly into Hobart in his polar ship Fram. The headline was in hindsight tragically way off the mark but it was not a deliberate ‘alternative fact’ of its day splashed across the established masthead. It was more an excited assumption based on expectation in the former British colonies of Australia and a misreading of Amundsen’s Nordic reserve on his arrival there after 16 months in Antarctica in his well-publicised contest with British naval Captain Robert Falcon Scott.

The Fram at Hobart, March 1912. From ‘Tasmanian Views’, an album compiled by Australian photographer E.W. Searle while working for J.W. Beattie in Hobart during 1911-1915. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

The Tasmanian press were bemused as the bearded Norwegian made his way between the telegraph office and his waterfront lodgings. With his expeditioners and crew quarantined on the ship on the Derwent River, the ‘mysterious’ Amundsen guarded his news carefully as he telegraphed his backers, the Norwegian King Haakon VII, his countryman, the famed Arctic explorer Fridtjof Nansen and importantly his publisher, London’s Daily Chronicle.

Only days later the news spread like wildfire with newspapers around the world publishing the febrile news that the Norwegian explorer, a ‘tall, spare quiet-mannered man, not un-English in his facial and general appearance…genial and kindly… a practical determined man of great intelligence and executive capacity’ [The Observer, 30 March 1912] was ‘the hero of the Pole’, reprinting Amundsen’s narrative in the Daily Chronicle and his telegram to King Haakon VII from Hobart, ‘Pole attained on 14 December, remained 17 December’ [The Observer 16 March 1912]. The return of Scott from Antarctica was expected in the coming weeks. The press literally tried to beat down the door of the Norwegian’s small room at the Orient Hotel.

Amundsen with the Norwegian King Haakon and Queen Maud, June 1910, Kristiania Harbour, Oslo. Image: Photographer Anders Beer Wilse courtesy Fram Museum.

Amundsen had visited Antarctica more than a decade earlier, in 1897-99, as First Mate on Adrien de Gerlache’s Belgica expedition, the first to spend the winter in Antarctica.

In the intervening decade, he focussed his attentions on the Arctic on a three-year expedition in his small 46-ton vessel Gjøa from 1903-06. From his base at Gjøahaven, King William Island, Nunavit he and six shipmates successfully investigated the movement of the magnetic north pole (first charted in 1831 by James Clark Ross). On 31 August 1906 Gjøa reached Nome, Alaska, and Amundsen became the first to navigate the elusive Northwest Passage. He then began planning to reach the North Pole in an attempt dressed as a scientific expedition to conduct oceanographic research replicating Fridtjof Nansen’s drift across the polar seas.

Possibly Amundsen’s first meeting with the Netsilik Inuit at his Arctic base Gjøahaven, October 1903, during the Gjøa expedition (1903-1906) that charted a passage through the north west territories. Image: Gjøa expedition 1903-06, Photographer unidentified courtesy Fram Museum.

After the North Pole was ‘won’ in 1909, claimed by both Frederick A. Cook and Robert E. Peary, funding evaporated and the Norwegian secretly turned his attentions south, to the unattained and equally highly-contested South Pole. He famously only revealed his plans ‘to take part in the fight for the Pole’ in Madeira in September 1910, on the voyage from Oslo ostensibly to Cape Horn, north America and the Bering Strait. Amundsen surprised his crew on board Fram and informed key supporters especially Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen who had furnished the expedition with his famous Arctic exploring vessel Fram. Amundsen’s confidante, his brother Leon, informed the press and telegraphed Scott in the Antipodes en route south. Scott was in port in Melbourne, Australia. The Norwegian Captain redirected his course towards the Cape of Good Hope and Antarctica, arriving at the ice barrier at the Bay of Whales, King Edward VII Land, 13 January, 1911.

Fram moored at the Bay of Whales, Ross Ice Shelf. Image: Photographer unidentified courtesy Fram Museum.

Amundsen established his camp on the ice itself, the Ross Ice Shelf, a full degree – 60 miles – closer to the Pole than Scott’s base across the barrier at Cape Evans, the site of previous initiatives in McMurdo Sound, 350 miles west. Both expeditions sledged to lay supplies before setting off for the Pole in the warm months late in 1911.

The ships’ men had met and dined together earlier that year in February, when the surprised crew of the Terror Nova encountered Fram in the Bay of Whales during a survey voyage looking for a mooring. Scott, on a sledging journey to lay a depot, had expected that Fram would moor on Antarctica’s Weddell Sea coast so the surprise was complete and the trek to the Pole silently intense.

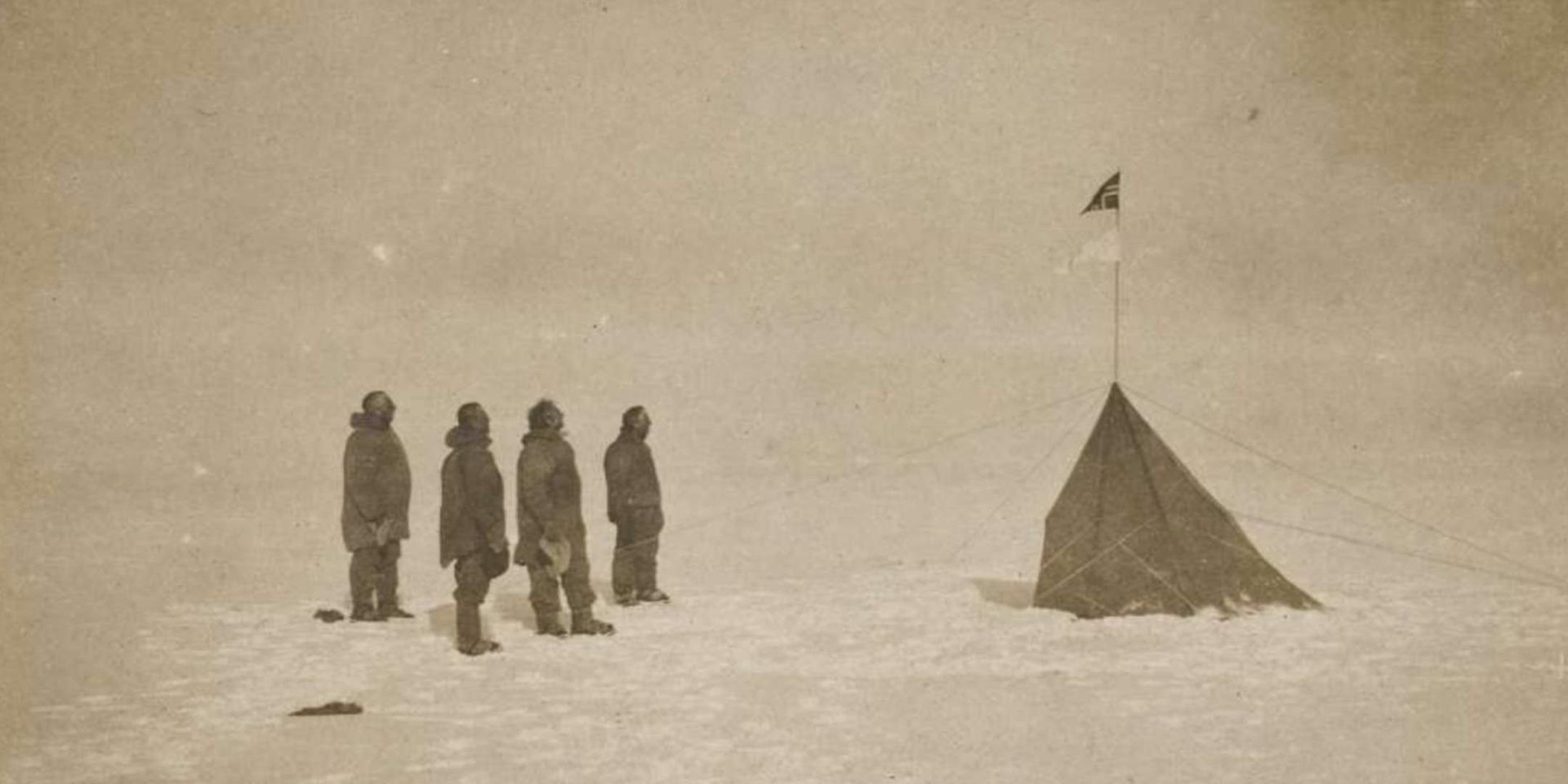

During that next summer, Amundsen was able to chart a new course to the Pole, arriving on 14 December 1911 with his sledging team Olav Bjaaland, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel and Oscar Wisting. Amundsen planted the Norwegian flag and Fram’s ship pennant at the place he named Polheim on the King Haakon VII plateau, nearly four weeks ahead of Scot. He marked the spot with a Norwegian flag and a tent, in which he left a letter to his King and to his rival.

The successful explorers at the South Pole, from left Roald Amundsen, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel and Oscar Wisting, December 17, 1911. Photographer Olav Bjaaland, the fifth member of the Poler team. From ‘Tasmanian Views’, an album compiled by Australian photographer E.W. Searle while working for J.W. Beattie in Hobart during 1911-1915.The expedition’s original South Pole photographs were developed and printed by E.W. Searle for Amundsen, 12 March 1912. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia.

The subsequent events of the summer of 1911-12 – Amundsen’s successful return and the death of Scott and his companions Bowers, Evans, Oates and Wilson – are legendary, as are the varying interpretations of the ‘race’, each expedition team’s dynamics, politics, judgement and decision-making, and the relationship between the two polar explorers. So too is the aftermath in the making and representation of national heroes.

On a very human level the details of the mechanics of Amundsen’s successful expedition are compelling – how did Amundsen win the race to the pole? How did he prepare for the extremes of the ice barrier and the Polar plateau? How did his choices of fur clothing, dogs over ponies, ski, sledge, tent and equipment design, nutrient balance in food rations affect his expeditioners’ daily lives to enable their success?

A new panel exhibition of images and text explores these choices. Curated and developed by the Fram Museum in Oslo the exhibition is drawn from original materials held in Oslo. It presents a fresh Norwegian perspective and features images taken on the expedition itself, by Amundsen, Bjaaland and other expeditioners, combined with insights from original expedition diaries, both sources that Roald Amundsen himself used in his obligatory lecture tour following the expedition.

More than an account of the travails of expedition life, the exhibition looks at Amundsen’s time in the Arctic and how he adopted and adapted experiences and encounters there. It was on his Gjøa expedition to chart the Northwest Passage that Amundsen first met Netsilik Inuit communities with whom he formed close relationships. He learnt a great deal about survival in the polar environment, about layering loose fur clothing, ice construction (igloo making), hunting, nutrition, sledge design, dog handling and much more.

Inuit trading Gjøahaven, Nunavut, 1904 or 1905. Image: Gjøa expedition 1903-06, photographer Godfred Hansen courtesy, Fram Museum.

The construction and layout of Amundsen’s Bay of Whales base at Framheim itself was modelled on Inuit communities with many of its workshops and accommodations built out of snow and ice and linked by a series of weatherproof passages.

He combined this with knowledge from his practical experience, Nansen’s patronage and expertise, and strategies for working with his small group of expeditioners, all drawn from Norwegians generally at home in snow or on skis. Comfort and warmth were critical, with the installation of a steam bath, also enjoyed on the Gjøa expedition, in Framheim.

Captain Roald Amundsen’s careful narrative of his expedition included his understated casual account of sledging to the Pole and back where ‘everything went like a dance’ [World’s News Sydney 13 April 1912]. Burnt by experience in losing funds, rewards from press rights from his Northwest Passage voyage, Amundsen, in common with his fellow polar explorers, controlled that narrative with a strong hand. He was feted in Hobart. After the Fram sailed for South America he undertook a two-week lecture tour entitled How I reached the Pole beginning in Adelaide, where his many well-wishers included the Chief Justice and the masters of the number of Norwegian sailing barques in Port Adelaide, Melbourne and ended in Sydney 6 April 1912.

Amundsen, billed as ‘The hero of the Hour’ and ‘the greatest celebrity to visit Australia’ by Punch [21 March 1912] illustrated his lecture with 100 coloured transparencies, lantern slides, many of which are on display in ANMM’s Vaughn Evans Library. This new graphic exhibition brings some of the polar adventurer’s Antarctic experiences to audiences of the 21st century, as if Amundsen were in the room, illustrating not ‘a dance’ but an incredible feat of endurance and skill.

When questioned about Scott, Captain Roald Amundsen replied ‘I do not see why he should not have reached the south pole and I think it is likely to be heard of anytime now.’ [Observer 30 March 1912]. It was not until the end of the following summer, February 1913, that the fate of Scott and his companions was confirmed and reported, to Amundsen’s great dismay.