While the dive team was busy documenting sites KR10 and KR11 on the morning and afternoon of 14 January, the magnetometer team took advantage of the calm weather and sea conditions to run a survey along the outside of the entire Kenn Reefs system. The first area surveyed was along the outside fringe of the ‘foot and ankle’, with specific emphasis placed on detecting offshore components of known shipwreck sites (such as KR1, KR2 and KR4). Because sea conditions were calm, the team also ‘deployed’ Lee on a tow-board behind the magnetometer.

The tow-board (also known as a ‘Manta-board’) is a flat, hydrodynamic-shaped board with handles that is connected to a towing vessel with a length of line. The person using the tow-board grips the handles, is pulled through the water at low speed, and can visually search the seabed for shipwreck material. Most tow-boards are designed so that their users can turn, dive and ascend through the water column at will, simply by changing its orientation with the handles. Lee was positioned 10 metres behind the magnetometer in the hope he might be able to visually spot and identify any anomalies it detected.

James Hunter (foreground) monitors the magnetometer readout aboard Maggie III while Paul Hundley pilots the boat during a survey run at the northern end of Kenn Reefs. Image: Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation.

As Maggie III pulled nearly in line with site KR2, the magnetometer recorded the project’s first legitimate anomaly—one that exhibited characteristics consistent with an historic shipwreck. Another promising target was detected a short time later along a section of the reef not known to possess any wreck sites. Curiously, Lee did not observe anything on the seabed at either location, which suggested the source(s) of the anomalies might be buried in sand or encapsulated in coral. Both anomalies were recorded with Global Positioning System (GPS), and Maggie III and its intrepid crew continued east and then north along the ‘foot and ankle’. By the end of the day, the team would also survey the outside of the ‘shin’ and ‘leg’, as well as a shallow lagoon within the ‘shin’. No additional magnetic anomalies were detected at these locales, and the team as a whole now focussed its attention on the two new targets.

On the morning of 15 January, Lee, Jules and I documented site KR11 with 3D photogrammetry, a relatively new recording technique used to produce digital models of submerged sites. The team tackled the task in three stages: Jules swam lanes across the entire site and acquired overlapping still images at regular intervals, while Lee filmed digital video along the same transects. My job was to capture detailed imagery of specific site features, such as individual anchors and carronades. I took multiple digital still images of these objects, ensuring at least 60-percent overlap between shots. Markers were placed on the seabed to define the boundaries of the site, and help Lee and Jules orient themselves and frame their photographs. Ultimately, selected images will be entered into a photo-modelling software program and combined to form a digital 3D model of KR11 and its prominent site components.

Lee Graham conducts a 3D photogrammetric survey of one of ‘Morgan’s anchors’ at site KR11. Image: Renee Malliaros/Silentworld Foundation.

While the photogrammetric survey was underway, two Silentworld crewmembers, Morgan Logan and Dave Gara, conducted a visual inspection and metal detector sweep of the surrounding reef. Within a very short time, Morgan discovered two large Admiralty-pattern anchors and a large iron frame in a series of gullies immediately to the east of the KR11 anchor cluster. She informed Jules of the new finds, who passed word to me and Lee. By this point, our photogrammetric work was largely complete, so the team finished its dive with a quick photo and video survey of ‘Morgan’s anchors’.

Meanwhile, John, Jacqui, Pete and Renee investigated waters immediately offshore of the scatter of large iron blocks and other modern material discovered on 13 January. Despite a comprehensive search, including within crevices and gullies that would typically serve as a collection point for shipwreck debris, no artefacts or features were encountered. This reinforced the team’s theory that the blocks and associated objects were all that remained of a modern vessel that grounded on the reef and was later re-floated.

Pete Illidge takes a ‘breather’ next to one of KR12’s broken anchors. Image: Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation.

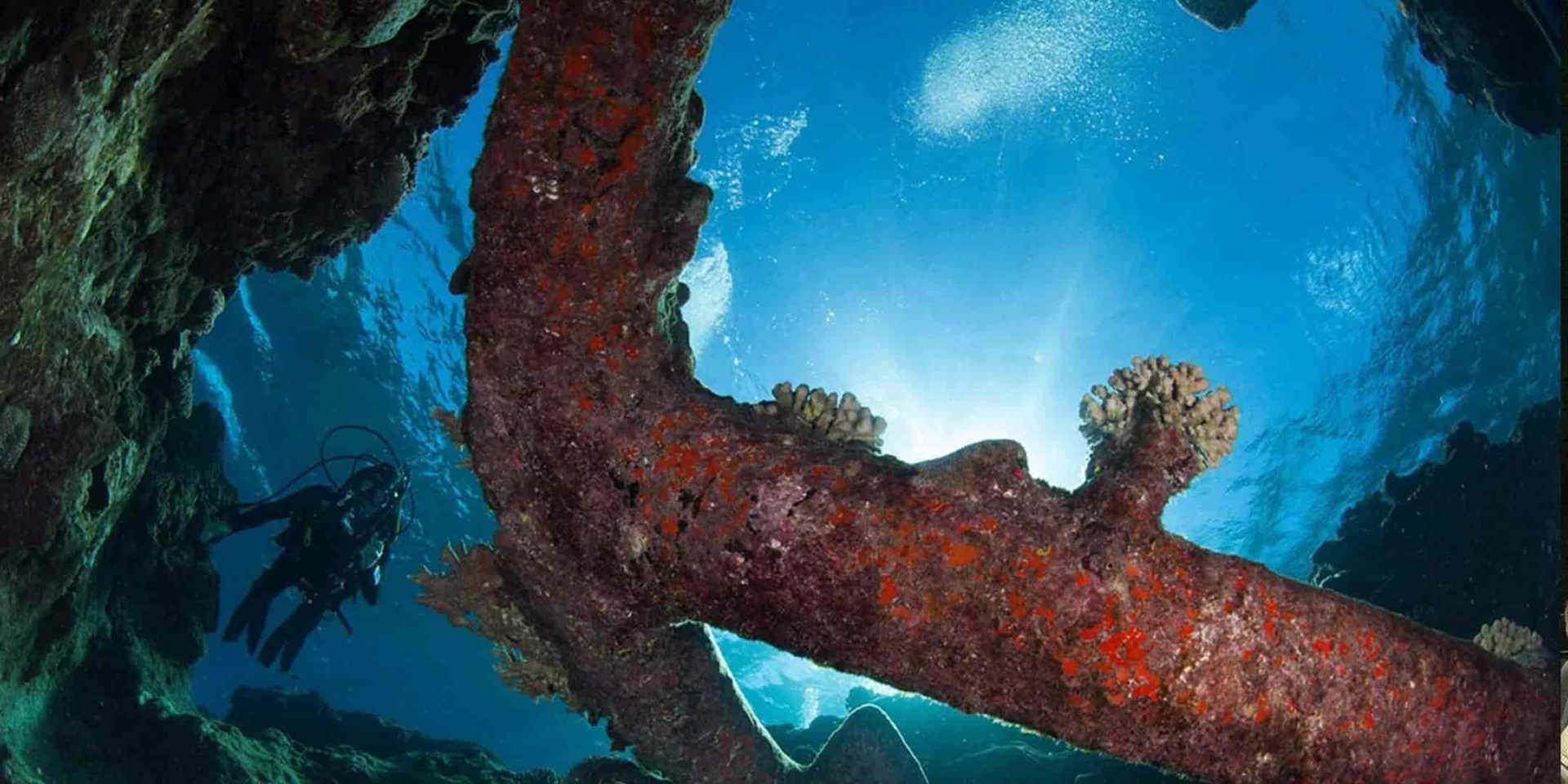

The photogrammetry team had a bit of time to kill before meeting the other crew and heading back to Silentworld, and decided to conduct a quick snorkel survey of one of the promising magnetic anomalies detected the day before. Within minutes of entering the water, Morgan doubled her tally for the day and found a new site (named KR12) comprising two broken Admiralty-pattern anchors laying a short distance from one another in two parallel gullies. The palm and part of the arm of one anchor had been snapped off, while the other was missing its entire lower section (including the crown, both arms and both palms).

John Mullen conducts a metal detector survey within a reef gully at site KR12. Image: Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation.

Just as the anchors were discovered, the other team arrived, and more people entered the water to participate in the search. In short order, two iron cannons were found nearby in a shallower section of reef. Both were relatively small (3- or 4-pounder) muzzle-loading long guns, one of which appeared to retain its tampion. Tampions were wooden plugs placed in the muzzle of cannon to prevent seawater and sea spray entering the bore and causing internal corrosion. They were often installed once a cannon was armed, and as this effectively sealed the bore, the possibility exists that ammunition, a wad and powder bag may yet be preserved within the example discovered at Kenn Reefs.

While certainly excited about the new finds, as a member of the survey team that detected KR12 the previous day, I felt something didn’t quite add up. The anchors and cannons were clearly capable of generating the type of signature recorded by the magnetometer, but they were further inshore and nowhere near the anomaly’s recorded position. This led me to believe the actual source was in deeper water, and I snorkelled along a depth interval that aligned with its GPS plot. Within a matter of minutes, I found what appeared to be a narrow copper-alloy plate with holes laying partially exposed on the seabed. No sooner was this discovery made than an even larger artefact—a copper-alloy rudder pintle measuring nearly two metres in length—came into view a short distance away. One of a number of large metal brackets attached to a ship’s rudder, a pintle featured a vertical pin at one end that was inserted into the opening of a corresponding bracket attached to the ship’s stern called a gudgeon. Together, pintles and gudgeons formed a hinge upon which the rudder rotated from side to side.

Close-up of a ship’s draught of a nineteenth-century East Indiaman, showing the pintle and gudgeon assembly that attached the ship’s rudder to the stern section. Image: Abraham Rees (1819), The Cyclopaedia, or a New Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences: Ship-Building. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, Plate XII.

I barely had time to mentally process these finds when I scanned the seabed again and spotted the unmistakable outline of a copper-alloy ship’s bell. It was laying on its side, with approximately one-half of its circumference exposed among chunks of broken limestone and coral rubble. Closer inspection revealed a series of embossed concentric lines cast around its top and base, but a name, date, and other identifying marks were not immediately evident. The bell was clearly a diagnostic artefact with the potential to reveal the identity of the ship from which it originated, but the team needed to follow a series of important protocols before its recovery could proceed and it could be examined in greater detail.

James Hunter inspects the ship’s bell at site KR12 shortly after its discovery. Image: Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation.

Shipwreck sites in Commonwealth waters that are at least 75 years old are automatically protected by the Historic Shipwrecks Act (1976). Protection under the Act also extends to relics (artefacts) associated with historic shipwrecks. The primary goal of this legislation is to ensure shipwreck sites are protected for their heritage values and maintained for recreational, scientific and educational purposes. The Act also seeks to control actions which may result in damage, interference, removal or destruction of an historic shipwreck or associated relic. Divers and snorkelers are permitted to visit historic shipwrecks for recreational purposes, but artefacts must not be removed and the physical fabric of the site must not be disturbed unless a permit has been obtained to conduct these activities. The expedition team applied for—and was granted—a permit from the Commonwealth government’s Historic Shipwrecks Program to carry out research at Kenn Reefs. Among the permit’s stipulations were provisions regarding artefact recovery. Excavating for artefacts was not allowed, and collection was limited to diagnostic specimens already exposed on the seafloor.

The team returned to Silentworld and consulted by satellite phone with ANMM’s Manager of Maritime Archaeology, Kieran Hosty, and representatives of the Historic Shipwrecks Program. All agreed the bell met the permit’s definition of a diagnostic artefact, and approved its recovery. A plan was then formulated to document the bell extensively in situ (in place) before lifting it from the seafloor. Upon arriving back at KR12, Lee and I set to work establishing a baseline and taking offset measurements to accurately plot the bell’s location and orientation on the seabed. The large pintle was also mapped, as were two additional pieces of rudder hardware located nearby. The copper-alloy ‘plate’ turned out to be either a pintle or gudgeon (too much of it was buried to make a positive identification), and the pin of a second pintle was found a short distance away protruding above a patch of sand and coral rubble. Each artefact was also individually measured, documented with 3D photogrammetry, and plotted with GPS. Once the bell was sufficiently recorded, John, Pete and Paul recovered it using a lift bag and system of lines attached to a small tender moored above the site. The lift only took a few minutes, and the bell was safely brought aboard the tender and transferred to Silentworld.

Future plans for the bell include conservation treatment to stabilise its metal fabric and gently clean away adhering marine growth and corrosion products. Copper-alloy artefacts that have been immersed in seawater for long periods of time absorb chlorides (salts) that are highly corrosive and can be extremely destructive if left untreated. Conservation techniques will be employed to remove these chlorides from the bell, and carefully expose its original surface so that surviving diagnostic information—such as a name, date, or manufacturer’s mark—may be revealed. Once conserved, the bell will be recorded in minute detail (including via 3D digital processes such as laser scanning or photogrammetry) and likely subjected to a variety of analytical techniques in an effort to determine where and when it was manufactured. This in turn may reveal the identity of the vessel to which it belonged.

Coming up in the next post: As the project winds down, one last surprise is revealed…

Explore more about the museum’s maritime archaeology initiatives on our blog.

With thanks to our maritime archaeology program partners, Silentworld Foundation.