Gumung derrka and Na-riyarrku: Sewn bark canoes

Sharing the waterways across the top of the mainland coast are a number of different types of sewn bark canoes. The museum’s three sewn bark canoes represent two distinct types. Two are Yolngu gumung derrkas – these are freshwater swamp and river craft. The other is a Yunyuwa na-riyarrku – it is a coastal saltwater craft. They show many of the features common to sewn bark canoes. The bow and stern are sewn or stitched together (giving rise to the descriptive name), the sides have gunwale branches, and different types of ties, beams and frames are used to give support across the hull.

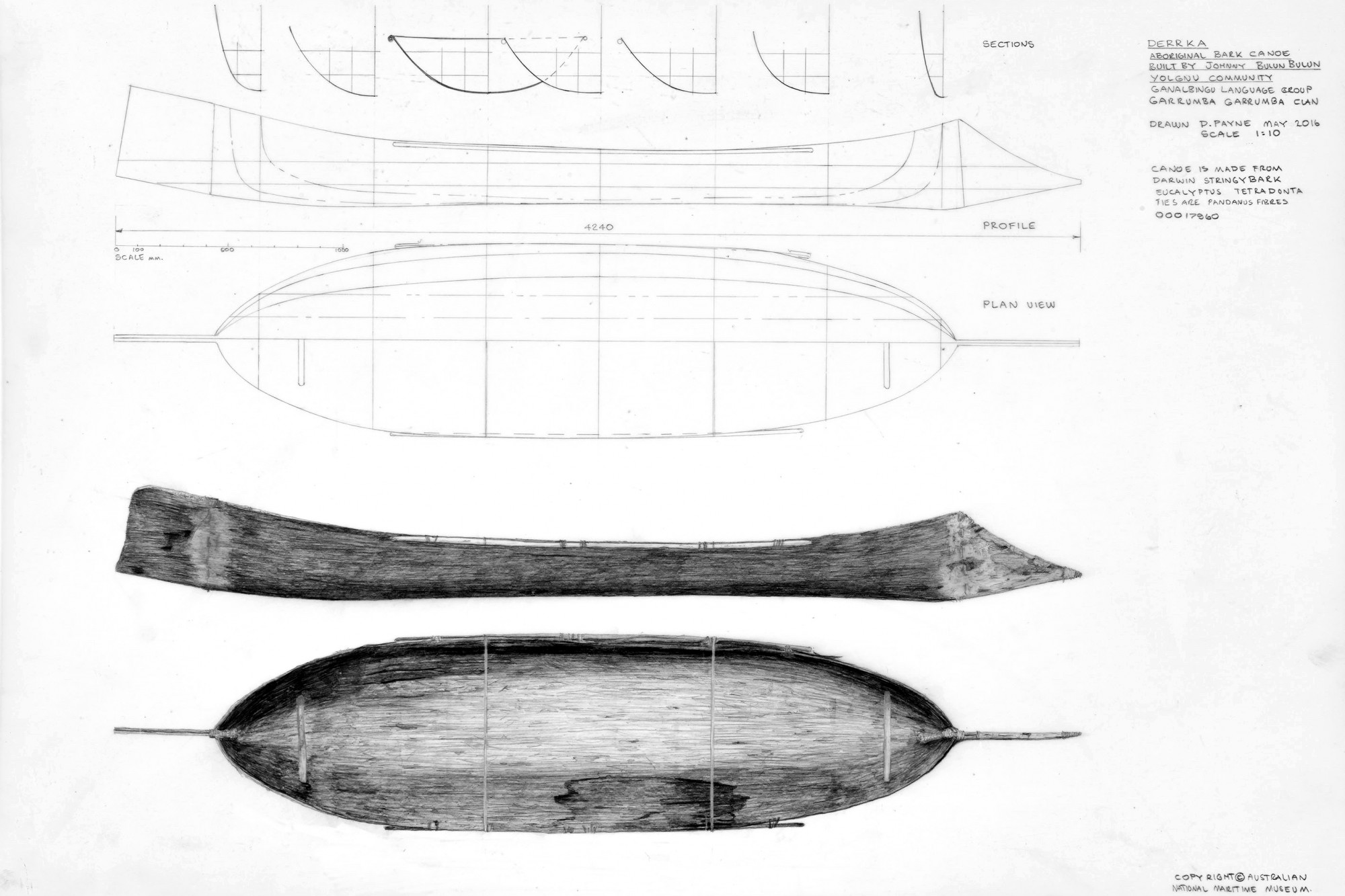

Gumung derrka. Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00017960.

Gumung derrka. Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00017960.

Gumung derrka. Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00017960.

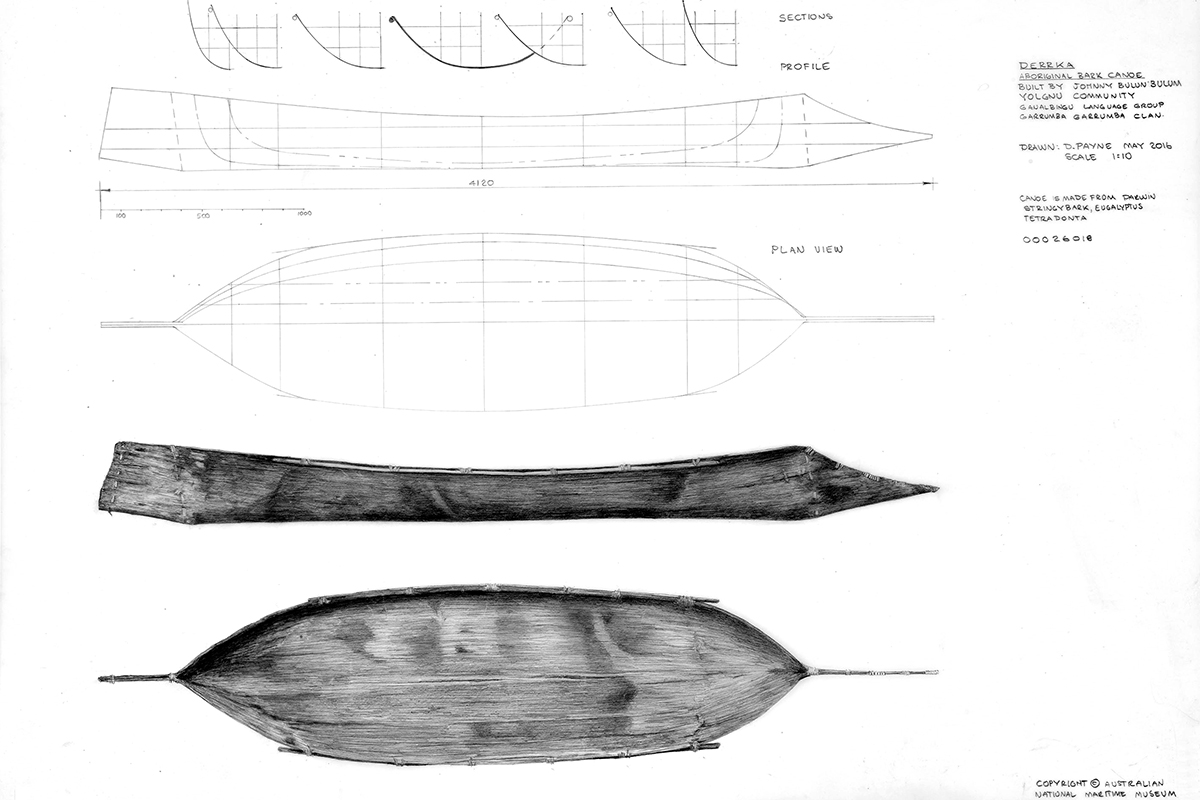

Gumung derrka. Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00026018.

Gumung derrka. Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00026018.

Derrka is the name for the canoe used on estuarine waterways. It has quite square, vertical ends, with a crease about 400 millimetres back from the ends, which are sewn together and sealed from the inside. The gumung derrka has a very distinct bow shape, cut back from the bottom front corner to the top of the crease, forming a distinct raked back prow. The stern is shorter but remains vertical.

The gumung derrka was used on the Arafura swamps that are connected to the Clyde River on the inland of Arnhem Land. The sharply raked bow – which is artistic to look at and gives the craft an impressive presence on the water – serves a vital purpose. When the monsoons come, the Clyde fills rapidly and the surrounding grasslands flood. The shallow but densely grassed lake that forms is home to gumung (magpie geese) and their nests. To push through to the nests, the canoes are poled along by each person, and the cutback bow gently and gradually parts the grass, allowing the craft to work its way through, whereas a square end would catch and become stuck. Moving as a group, Yolngu people hunted from these canoes for gumung and their eggs in the wet season’s flooded Arafura swamplands

Gumung derrka. Image: Andrew Frolows / ANMM Collection 00017960.

On the open water in the river they sat toward the middle and paddled with both hands. The craft were relatively large, about 4.5 metres in length, and could easily carry a load of geese and eggs.

The museum’s first gumung derrka was purchased through Maningrida Arts and Culture in the Northern Territory, while the second one was bought through the Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi , Melbourne, Victoria.

Gumung derrka. Image: Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi / ANMM Collection 00026018.

Gumung derrka. John Bulun Bulun and Paul Pascoe bind the stern. Image: Dianne Moon / ANMM Collection 00017960.

The craft built in 1989 includes two beams at the forward and aft end, a clay and fibre sealing piece in the vertical end joints and clay markings on the bow. Its construction was documented in a series of photographs by Diane Moon. These show the process from taking the bark, the use of fire to heat the ends, sewing the seams and finishing the craft.

The second craft is a cleaner example of the type. There no beams or sealing materials, and fewer loose fibres on the inside surface, which is the outside of the bark. An interesting difference is that the absence of beams has made the ends of this craft less rounded and reduced the volume, giving this example a sleeker appearance. It suggests that the builder made the first as an exact example of the traditional working craft, but for the second commission reinterpreted some of the details so that it was more of an art piece for display.

They are both excellent examples and through these differences show the capabilities of the builder and reflect how impressive these craft can look.

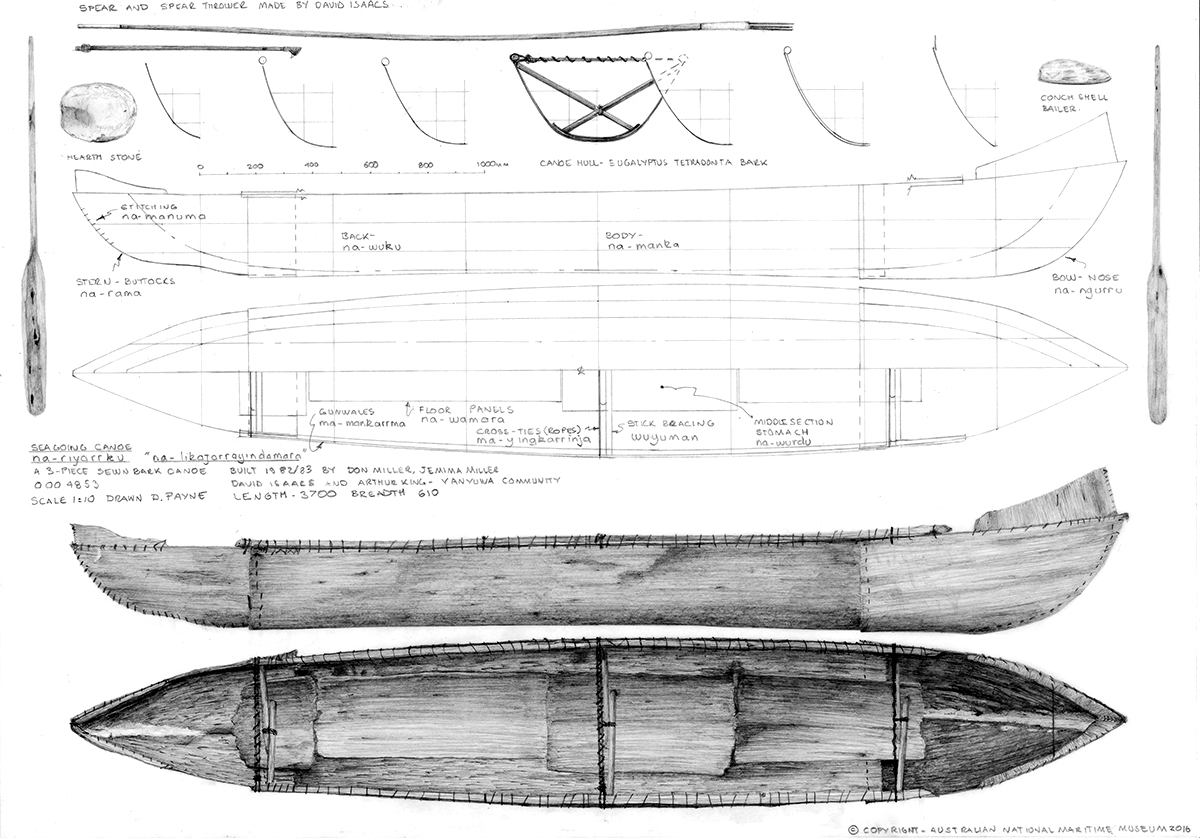

Na-likajarrayindamara is a na-riyarrku seagoing sewn-bark canoe from Borroloola in the north-east of the Northern Territory. Don Miller, Jemima Miller, David Isaacs and Arthur King from the Yanyuwa community were commissioned by the museum to build this seagoing canoe, and the process was documented by John Bradley in 1988. The name Na-likajarrayindamara refers to the place it was built, Likajarrayinda, just east of Borroloola, and it is Yanyuwa practice to name canoes in this manner.

Na-riyarrku. Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00004853.

Na-riyarrku. Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00004853.

A na-rnajin is a bark canoe made for rivers and lagoons and comes from one section of bark, but the na-riyarrku has a special bow and stern piece added to make it a sea-going craft. These relatively large canoes were used for fishing on the coastline of the Gulf of Carpentaria. One person would paddle, while one or two others seated aboard searched for fish, with four-pronged spears at the ready.

They were strongly built for their purpose. The hull is made from three sections of stringybark, carefully overlapped and sewn together and sealed with clay and mud. It is made from a tree common to northern Australia, the Darwin stringybark Eucalyptus tertradonta (also referred to as a messmate), and sewn with of strips from the split stems of the climbing palm Calamus attstrali. The middle section is quite long, while the shorter bow and stern sections have their freeboard raised with further pieces of bark sewn to the main hull.

The hull is held in shape using a form of cross bracing between the gunwale branches at three locations. This was forced into place and then tied together to form a rigid triangular configuration that stiffened the main body of the hull. This is an excellent example of strong engineering using a bracing concept that many would think had only been applied to structures as a more recent concept. It should also be noted that the cross bracing was only used on the na-riyarrku sea going craft, the na-rnajin lagoon canoes just used a beam and a tie for stiffening and support.

Na-riyarrku. Image: Andrew Frolows / ANMM Collection 00004853.

Interior view of Na-riyarrku. Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00004853.

In the early 1800s this type of craft was recorded at the Sir Edward Pellew Islands that are just offshore from Borroloola. The report from Captain Matthew Flinders, who was charting the region, described the craft and noted in the detail their gunwales of mangrove poles lashed to the bark hulls, obliquely arranged wooden struts combined with a series of ties to maintain the spread of the bark, and short wooden wedges placed in the bow and stern for the same purpose. On the floor were flat pieces of sandstone that served as a hearth. The museum’s example has almost all these features, along with the additional bark sheets on the floor of the canoe, a conch shell bailer, two paddles and a four-pronged spear.

Yuki: A sheet bark canoe

The Murray Darling River system includes both rivers, many tributaries and adjacent rivers or lakes, and forms a wide ranging area in the south-east inland. It is Australia’s largest inland waterway system. It is home to a large number of Aboriginal freshwater communities, and it is home to a distinct type of canoe, a single sheet of smooth bark formed into a boat shape.

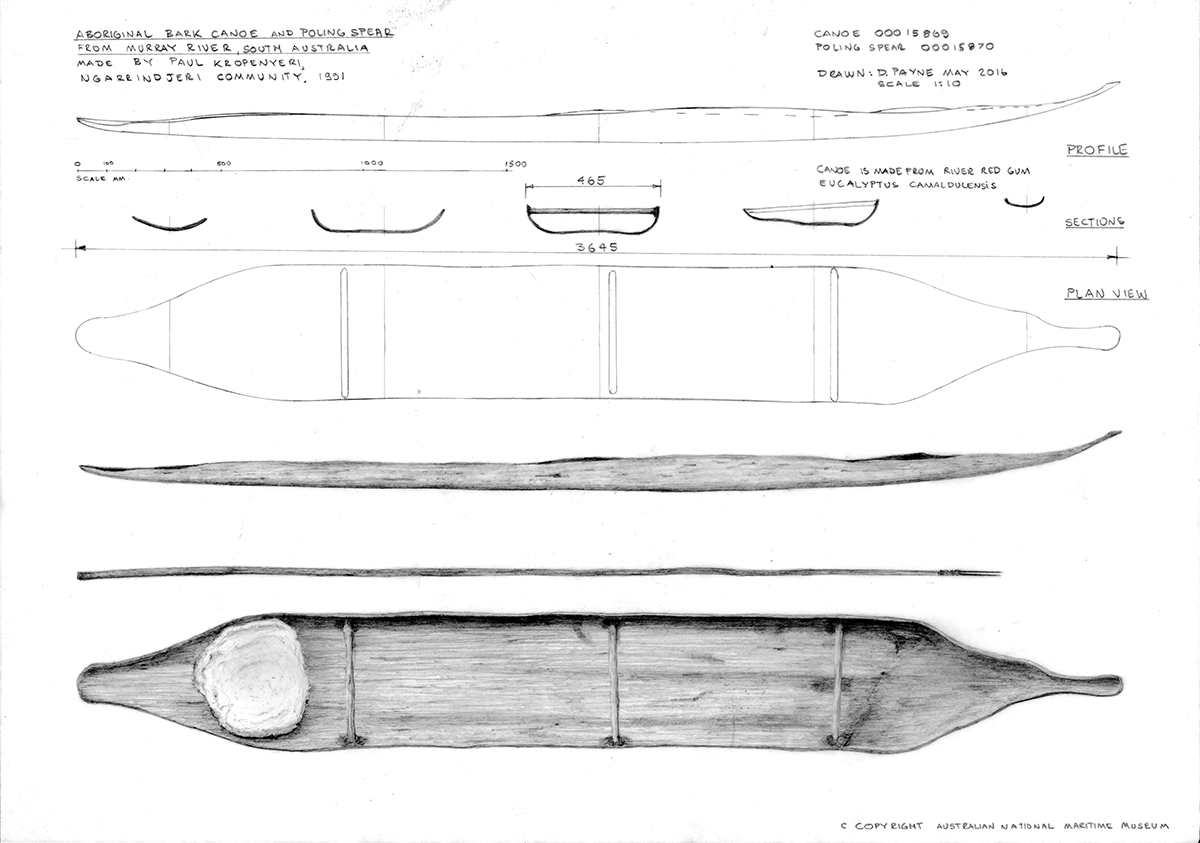

In South Australia it known as a yuki, the name used by the Ngarrindjeri people. Paul Kropinyeri from the Ngarrindjeri community made the museum’s yuki. It was purchased through the Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute in Adelaide SA.

The widely distributed river red gum Eucalyptus camaldulensis was primarily used for their construction, and the craft are well known through the many scar trees that still remain in the region, showing where the bark was taken. It has also been recorded that other barks were available and used, including black box Eucalyptus largiflorens and Eucalyptus rostrata, which have closely knit, smooth fibre surfaces.

Yuki.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00015869.

Yuki.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00015869.

A small number of photos taken during the construction have helped record how Paul Kropenyeri made this example that came into the collection in 1991. A long section of bark from a river red gum was cut and peeled off the trunk, and it is often taken where a gentle bend contains the elements of a curved canoe profile. He then weighted and cured the bark over one month to help form into its elegantly simple shell, supported with just three eucalyptus branch beams.

Standing to pole it along, the hunter and canoe were cloaked with the river’s mist and smoke from a fire on a mud hearth toward the rear, perhaps cooking a freshly speared fish. Kropenyeri provided a pole for the museum’s yuki as well, with prongs for spearing fish.

The Murray Darling River system is Australia’s largest inland waterway system and home to a number of Aboriginal freshwater communities.

From examination of other examples it is known that the single sheet of material was often up to 25 millimetres thick. The bark was usually manipulated further to improve this shape using heat from fire and soaking in water to help soften the bark, and even by creating a mould in the earth into which the bark was pressed and gradually formed into a better shape. It is common to have two or more beams to keep the sides apart, and the ends sometimes had clay added to stop water coming in. Some were big enough to carry a number of people.

As a long and narrow dish-shaped panel they are remarkable. The bark provides a single thick panel of tightly woven fibres that run in opposing directions through the many layers within the thickness of bark, and this gives it is a tough and rigid shape. The addition of two or more beams to hold the sides apart adds to the overall stiffness. It’s ideal for the many lakes and rivers these craft are found on, where for much of the time the waves are small and high sides for freeboard are not often needed. The raised bow and stern seen on most of the craft would have helped it ride over the small waves. Stability largely came from the width and cross-section shape, relatively flat through the middle with a stronger curve up to and into the sides.

Yuki. Paul Kropenyeri with the tree he used. Image: Photographer unknown / ANMM Collection 00015869.

Yuki. Paul Kropenyeri with the finished yuki, pole and another smaller version. Image: Photographer unknown / ANMM Collection 00015869.

One of the outstanding points is that this is virtually a complete monocoque construction, a single panel with almost no additional framing, girders or other structure, only the two or three beams holding the sides apart. Monocoque (‘single shel’l in French) is often considered a modern construction method, pioneered by the French in the early 1900s era of aircraft construction, where they were seeking to engineer a light and stiff fuselage. Here is an example of the same concept that is potentially some thousands of years older in its application and understanding. The yuki also reflects a very simple craft with just the minimum parts needed to become a boat.

Rra-muwarda or Rra-libaliba : A dugout canoe

The introduction of the single hulled dugout canoe is understood to have happened when Macassin traders from Indonesia came to areas of the northern Australia coastline to search for beche-de-mer and trepang. This commenced as early as the 1500s. Their visits were conducted on a regular, seasonal basis, and in time they began to interact and trade with the Aboriginal communities. This exchange included trading examples of their dugout canoes and then the skills and tools to build them. Dugouts are now found throughout the whole northern region, from the Gulf of Carpentaria, across Arnhem Land and as far west as the Kimberleys in WA.

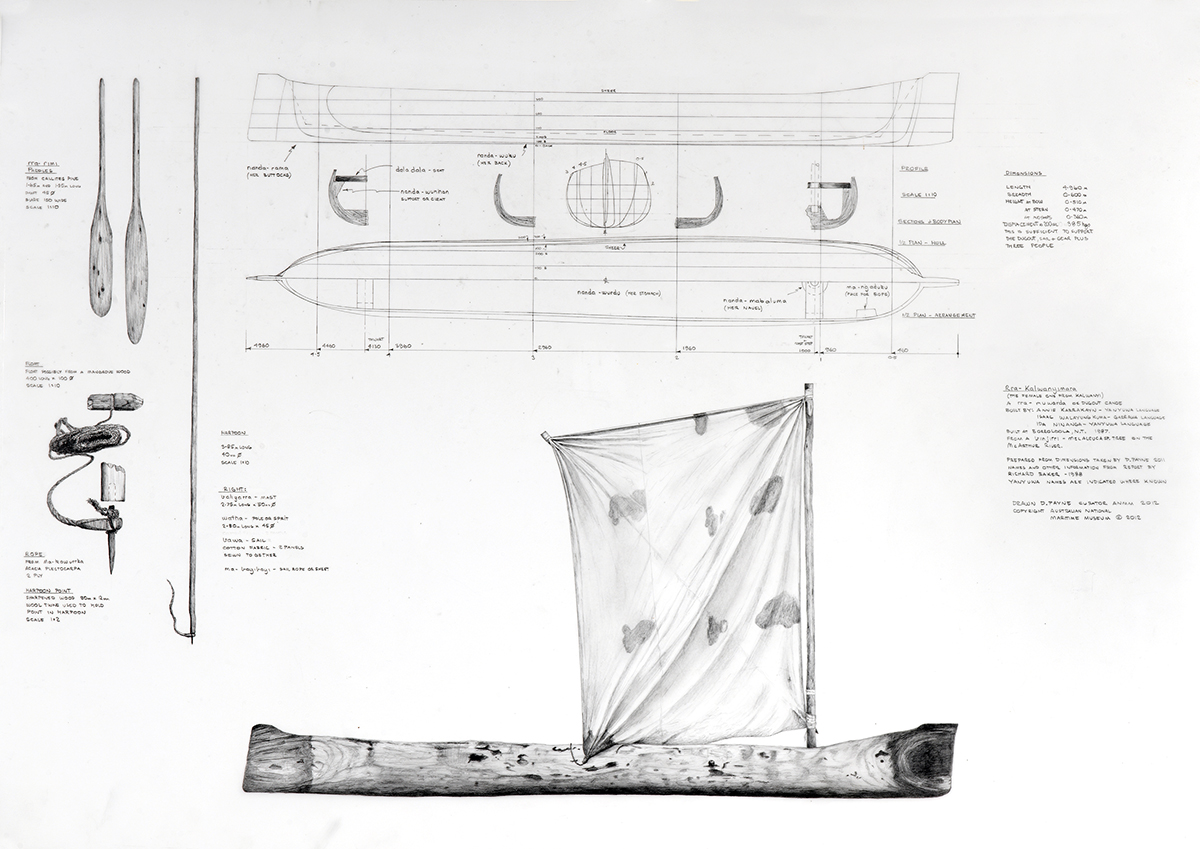

The museum’s dugout canoe and was made by Annie Karrakayn, Ida Ninganga and Isaac Walayunkuma from the Yanyuwa and Garrawa peoples and is also from Borroloola. The construction was also documented by Richard Baker in 1988. It is called a Rra-muwarda or Rra-libaliba and was named Rra-kalwanyimara which means ‘the female one from Kalwanyi’, reflecting the location where it was made. The term lipalipa is also widely used to name the dugout type, and some dugouts were fitted with a sail. Ninganga and Walayunkuma were both experienced dugout canoe builders.

Rra-kalwanyimara.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00001826.

Rra-kalwanyimara.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00001826.

The canoe was built from a selected trunk of a Melaleuca known as Binjirri in Yanyuwa. It is hard to work but makes a long-lasting canoe. It was felled where the canoe was built at a lagoon called Kalwanyi, hence the name Rra-kalwanyimara.

In general terms the dugouts appear to follow the Makassan style with a stem and stern shape cut into the ends. The hull is shaped and hollowed out from a trunk in a careful process to avoid the trunk splitting and becoming unusable. The sides are carved to a thinner wall thickness than the bottom and the heavier bottom section helps the craft retain considerable strength. It gives a rigid cross section despite the long and wide opening created on the top surface.

Rra-kalwanyimara.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00001826.

The taper of the trunk makes the shape larger and more buoyant at one end, and the craft’s use seems to take this into account for advantage. The craft carries two people; a paddler sits aft in the narrower part, while the hunter stands forward with his spear and cable in the fuller section, where there is more room and it is more stable.

Rra-kalwanyimara.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00001826.

Rra-kalwanyimara.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection 00001826.

A well-cut dugout has considerable strength; the trees used are relatively dense and strong in themselves. The axe and adze marks over the hull reveal the effort put into shaping the log. The thwarts help stiffen the craft as well, and serve to keep the sides apart and not creep together as it dries out. Their mass is not inconsiderable and this helps with overall stability.

Fitted with a sail, harpoon and float, these canoes were used to hunt dugong in the Gulf of Carpentaria. The museum’s dugout has these items and two paddles to give a complete picture of their use.

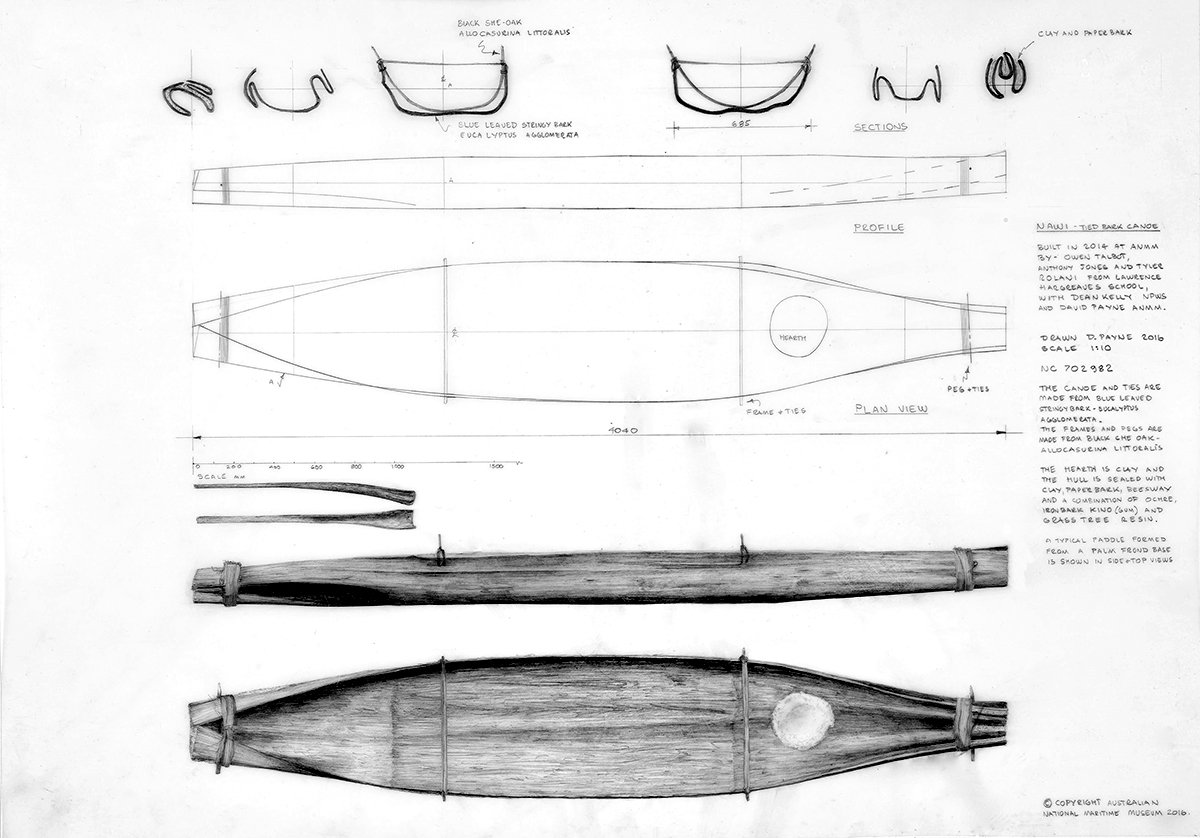

Nawi: Tied bark canoes

Outside of the collection but forming a vital part of the museum’s Indigenous programme are nawi tied bark canoe projects that have developed experience building full size craft. These have been made in workshops and gatherings for community and supported by the museum, starting back in 2012. One of these is a nawi made as a project involving Aboriginal students Anthony Jones, Tyler Rolani and Owen Talbot from Lawrence Hargreave School in Liverpool Sydney, in association with Dean Kelly, Indigenous Community Liaison Officer with NSW NPWS, and staff from the museum.

This nawi is now on display at the museum in our Indigenous gallery space, and was built and launched in 2014. The bark was collected from the Wattagan State Forest in association with Forest NSW Central Coast, and the boys had an excursion to the region to see the country where the material was sourced. They then attended the museum where the canoe was formed into shape over the course of the day. A few weeks later the nawi was taken to the school where it was finished off, and a large community gathering was held, bringing people together and allowing the boys to show their project to everyone. The final stage was to launch the craft in nearby Chipping Norton Lake at another community gathering complete with a smoking ceremony a month later.

Nawi.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection NC702982.

Nawi.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection NC702982.

Nawi is the Gadigal and Dharug word for the tied bark canoe and this type was made along a large stretch of the eastern coastline from the Sunshine coast in Queensland down to the Gippsland region in Victoria. Each community has a different name for their craft and many have different details and features, but all share the concept of folding and securing the ends to create a canoe hull, which is supported by different arrangements of beams, frames and ties. Their size varies too, with some of the the largest coming from the Gippsland areas.

Stringybarks were used in most areas, including yellow stringybark Eucalyptus acmenoides, Eucalyptus muelleriana, and Eucalyptus umbra, white stringybark Eucalyptus globoidea and blue-leaved stringybark Eucalyptus agglomerata. Swamp mahogany Eucalyptus robusta is not a stringybark but it has been used along the north coast of New South Wales and into Queensland.

Nawi.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection NC702982.

Nawi.Image: David Payne / ANMM Collection NC702982.

The long fibrous strands of the bark are ideal for a strong hull, and most have the bark inverted so the smooth, resin-rich inside surface becomes the outer surface on the canoe hull. The ends are folded and tied together after the ends have been thinned down, then heated over a fire to make it easier to crease. These folds are often fastened with a peg as well.

The stringybark often gave material for rope and ties, but vines such as five-leaf water vine Cissus hypoglauca and running postman Kennedia prostrata were also used to bind the ends and tie the sides together.

The craft were commonly paddled by hands or with short bark paddles while seated or kneeling. The bases of cabbage tree palms also provide a suitable paddle. They could even be poled along, especially the large canoes from the Gippsland Lakes region. A fire could be carried on a hearth of wet clay.

Around a dozen nawi have been made through museum workshops in a number of locations in and near Sydney, and collecting the bark has been part of the process. All of the projects have been held with a community consultation and cultural connection and the knowledge of their construction has passed on and been practised.